The Mint of the United States of America in Philadelphia

A visit to the year 1885

Article 1, section 8 of the Constitution of the United States of America reads as follows: “The Congress shall have power … to coin money“. To effectuate that theoretical privilege, the Congress charged the Minister of Finance Alexander Hamilton on April 15th, 1790, with presenting a concept for a mint. Two years later, on April 2nd, 1792, President Washington himself authorized the Mint’s building. The Mint was the first building that the newly established Confederate States erected for the use of the community.

Philadelphia Mint, exterior view.

The Philadelphia Mint had already moved on from that elementary stage when in 1885 a comprehensive guide was published. As early as 1829, the Philadelphia Mint had moved to a new, bigger building since the need of coins of the United States of America had greatly increased.

So had the number of onlookers. Whereas at the beginning of the 19th century the director of the Mint had to personally permit every visitor, in the 80s there were regular opening hours for the public. Between 9 a. m. and twelve noon, except Sundays and legal holidays, the public was allowed to look at the employees of the Mint minting coins of gold, silver and base metal. 40,000 visitors each year took advantage of that opportunity.

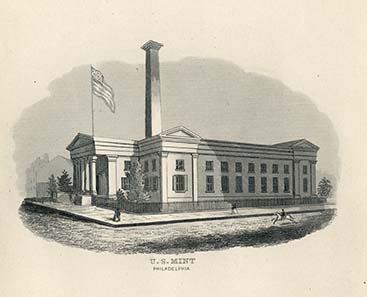

Beam balance.

The guided tour started off in the store or weighing room where all gold and silver that had been transported to the Mint as raw material was meticulously weighed and registered. The measures used for the dial balances, which were calibrated every second day, ranged from 1,4175 kilograms (= 500 ounces) to 0.02835 grams (= 1/1000 ounce). The major part of the gold came from California where rich gold deposits had been discovered in 1848. At least two employees of the Mint had to be present when the weighing was done to prevent any manipulation. Afterwards, the precious metal was locked in an iron box with two locks – two employees working at the molten bath had the keys to these locks. In the molten bath with its four furnaces the box was unlocked, the metal was melted and brought back to the weighing room where the material was weighed again and the coin examiner took a sample of the metal.

The Mint in Philadelphia was proud of its coin examiners and their accuracy. The smallest measure they used was 0.0000498 grams (= 1/1300 grains). That measure was so tiny that the naked eye was able to see it only against a white background. Such small measures were necessary since only half a gram of the material to be checked was available for the measurement of the metal composition. That half a gram was stated as 1000, every part was referred to as a fraction of that number. 900 gold designated therefore a fineness of 900 parts gold.

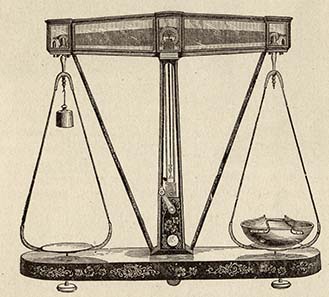

A smelter founds the bars.

After the examiner had checked on the fineness of each metal load it was brought to a room where the right metal composition for the coins was artificially created. After all, the composition and hence the value of raw materials of gold and silver dollars shall not vary. Based on the analysis of the examiner the smelter prepared the alloy of the metal and founded bars in an oblong and narrow shape that were very well suited to be processed further to blanking strips. The room in which the smelter worked was equipped with a special floor: it was made of iron and had a slightly receding honeycomb pattern. In the small recesses the gold remains collected themselves so that the gold powder did not attach to the workers’ shoes and hence was not carried outside. Whoever cleaned the room was carefully watched because between 1880 and 1885 alone the powder added up to gold worth 155,000 $.

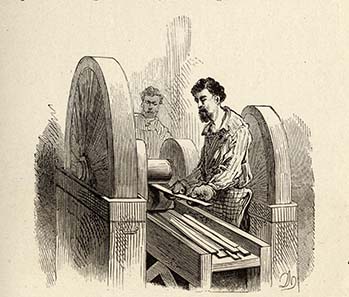

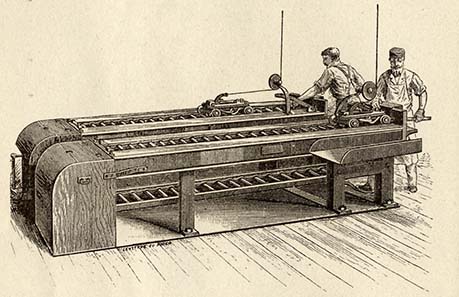

The rolling mill where the bars were rolled to coarse strips.

The founded bar was further worked on to become a strip as the basis for the production of planchets. It was brought to the rolling mill where it was coarsely hammered before it was processed in another mill. That mill’s roller could be set to any distance so that the strip was rolled slowly, step by step, starting from its original thickness to the thickness of the planchet. A gold strip had to be milled ten times, a silver one eight times. Every milling operation was followed on by a annealing of the strip to prevent the brittle metal from cracking. After this operation the strip was six times longer than the original bar. The modern rolling mill of the Philadelphia Mint processed 200 bars per hour. The friction caused such great a heat that the huge iron supports, which were attached to the machine and weighed several tons, got so hot that they the bare hand could not touch it anymore.

Machine for rolling the strip to reduce it to the required thickness of the coin to be produced.

No strip left the mill in uniform thickness. It had to be rolled, therefore. The machine for rolling the strip of the Philadelphia Mint consisted of a long table with an iron box at its end. Inside this box there were two iron cylinders standing upright that rolled the strip with high pressure to the thickness required for the planchet. One side of the metal strip was hammered a bit thinner to make sure that it ran through the mill without any problems. That end passed the iron cylinders first and was gripped by tongs which were attached to a little carriage pulled by chains. That carriage pulled the strip through the two small rollers at uniform speed. After the complete strip was rolled, a tong attached to the carriage pinched off the thin end to the effect that the metal blanking strip had a uniform thickness.

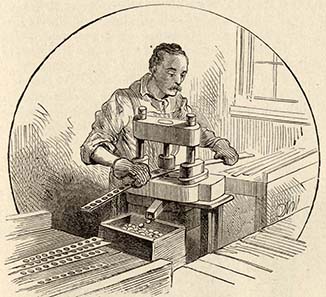

Blanking machine.

These strips were washed before they were transported to be blanked. The operation was quite similar to the automatic cutting out of Christmas biscuits with a cookie cutter. Blanking, however, needed more energy, and a higher speed was achieved. In 1885, the blanking machines of the Philadelphia Mint were able to produce 125 planchets per minute. About three quarters of a blanking strip were converted into minting blanks. The remaining metal was brought to the molten bath again where it was melted to become new bars.

The next step was the exact adjustment of the planchets. Already during the blanking it was made sure that the planchets were slightly heavier and by no means lighter as laid down by the law. Afterwards, the planchets were transported to a room where only women sat which weighed each piece by hand again, picked out the ones too light and decided with the ones too heavy whether they had to be picked out, too; often their edge could be abraded a bit to reach the ideal weight after all. The visitors were amazed about the certitude with which the women knew how much they had to abrade exactly to balance a certain difference in weight.

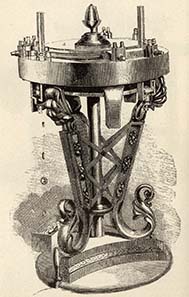

Engrailing machine.

By another operation it was made sure that the weight of the planchets stayed correct when circulating. Filing off raw metal was prevented by a specifically marked edge. For that reason, all planchets had to run through the engrailing machine. They were poured into the machine from above, through two horizontal pipes, where they were squashed between two wheels working in opposite direction and running in a distance slightly smaller than the planchets’ diameter. The minting planchet ran a quarter turn in the machine – in the process, its edge was compressed and pulled upwards a little bit. The machine worked at an incredible speed. It could process 560 fractions per minute. When it came to the bigger denominations, the speed was reduced. With the big 1 dollar pieces 120 planchets per minute was the limit.

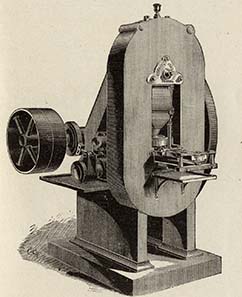

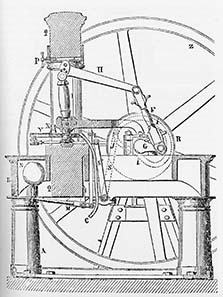

Improved coin press following the principle of the Uhlhorn knuckle-joint press.

Ten of the improved variant of the steam driven press introduced in 1874 stood in the minting room. The Philadelphia Mint, therefore, was one of the state-of-the-art mints in those days. The presses had different sizes according to the denominations they produced. They ran with an exactitude and a speed hitherto unparalleled. By using these presses, the die wear was reduced by more than 75 %.

Sketch illustrating how the knuckle-joint press worked.

The principle they followed was still the same as it had been since the introduction of the Uhlhorn knuckle-joint press in 1817. It based no longer on the even motion with which the obverse die was lifted and lowered but on the “pincer” of the obverse and reverse die which was made flexible by several knuckles. By a band wheel the jointed arm was put into circular motion – operated by horses at first, driven by steam later – , lifting the obverse die and making it hit the reverse die at full tilt. The planchets were added through a pipe. Since that task did not require any physical strength it was done by women.

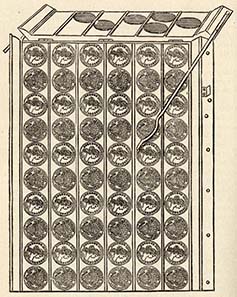

The calculation board was used to quickly count the minted coins.

Before the coins were minted they were checked, counted and packed. The gold coins were packed in bags worth $ 5,000, the 3 Dollar pieces in bags worth $ 3,000 and the 1 Dollar pieces in bags worth $ 1,000. The coins were not counted by hand but by using a calculation board the pieces were poured in. With this method it was possible to count 500 coins in less than a minute.

In 1885, about 300 persons were employed at the Mint, two thirds men, one third women. They worked six days a week from 5a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays, and to 2 p.m. on Saturdays, respectively. Alcohol being a problem in those days is attested by the house rules which laid down that it was prohibited to start work being drunk. Smoking and drinking during work was prohibited, too.

The souvenir book available for purchase by visitors of the Philadelphia Mint in 1885.

After visiting the Mint, the visitor could buy in the gift shop a number of medals for prices ranging from 25 Cent for a silver medal with the portrait of George Washington with a 10 mm diameter to $ 8 for a portrait medal of Major Grant with a diameter of 60 mm. Apart from that, there was a finely bound book with 160 pages available which documented and illustrated the work of the Philadelphia Mint which served a s a basis for this paper.