Akbar – Ruler of the Mughal Empire Part 2

Mysticism and God

Akbar was considered to be “ummi”, a word that some historians translate as “illiterate”. One cannot but be puzzled about that. Akbar’s great achievements in the field of administration and his keen interest in mysticism and religion make it seem strange that such an intelligent man did not learn how to read and write.

In fact, Akbar’s illiteracy must probably be understood in an entirely different context: in Islamic mysticism, the word “ummi” describes an inspired mystic who, gifted by God, does not need to learn anything because all knowledge falls into his lap. There are Muslim mystics who wrote numerous books and were still considered “ummi”. Thus, this little word gives us a hint as to how Akbar portrayed himself as a divinely inspired ruler.

In fact, most believers probably did not know what religion Akbar adhered to. Orthodox Muslims criticised his tolerance towards Hindus, his huge harem – after all, “only” four wives were allowed – his pleasure in wine and the beautiful miniatures commissioned by him. They must have considered it uncanny when Akbar imitated the customs of Indian yogis and Muslim Sufis, had his hair cut, lived a vegetarian lifestyle and even tried to deliver the Friday sermon.

His delight in speculative matters was a breeding ground for many rumours. Among other things, he was said to have carried out the famous experiment on the “natural language”, while western countries generally believe Emperor Frederick II to be the inventor of it: he forbade wet nurses to speak to the new-born infants, hoping to find out which language was the oldest one of mankind.

Religious Tolerance

Akbar was interested in everything relating to religion. That’s why some Portuguese missionaries had high hopes for being able to convert him since he received them just as amicably as their counterparts of the other faiths. They misinterpreted his curiosity as a special interest in the Christian faith. But Akbar’s plans were of a different kind.

The ruler of an empire that was inhabited by Hindus and Muslims was looking for a way to reconcile both religions. To this end, he first had to limit the influence of Muslim priests. He did this by issuing a decree in 1579 that made sure he had the last word whenever a scholarly dispute arose regarding the interpretation of a passage in the Koran. Moreover, every measure taken by Akbar in favour of the empire was to be recognized by everyone unless they could prove that there was a contradiction with the Koran.

Some misunderstood this act as a “decree of infallibility”. In fact, it did nothing more or less than granting Akbar the same position that a baroque Sun King was to assume in France barely a century later. And this was only the first step towards Akbar’s personal religion, which he proclaimed as Din-i-Ilahi (= God’s religion) in 1582.

Based on the principle that there was truth to every faith, Akbar tried to find the concepts that were common in all religions: In his opinion, one God, the Creator of the world was above all people. From the Jains he adopted the appreciation any form of life, even of the lowest creatures, the animals. The followers of Zoroaster inspired him to worship the sun. Even though Akbar’s glad tidings did not survive his death, they are propagated occasionally as a form of Islam that seeks to reconcile Hindus and Muslims in India.

The Administration of an Empire

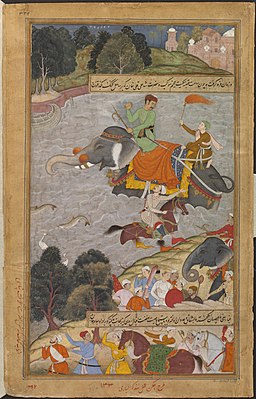

The sheer size of his empire caused Akbar to face enormous problems. About 100 to 125 million people are believed to have lived in the Mughal Empire at that time. Of course, there were some large cities: Agra, for example, was larger than London at the time, and Delhi wasn’t much smaller than Paris. Nevertheless, most people in the villages made their living from agriculture.

Therefore, Akbar got most of his financial resources from land value taxes. The income of the central government depended on his ability to assess and collect taxes correctly. For this purpose, Akbar could draw on preliminary work that Sher Khan had done during his reign. Under his rule, the land had been surveyed. Since then, a tax assessment had been carried out every year at harvest time to determine the tax rate based on the weather and the expected yield. This task was so important that the ruler himself made the decision.

Due to Akbar’s expansion, the system became outdated. It was impossible to fix a uniform tax rate since the climate wasn’t the same in different regions of the empire. Moreover, large parts of the territory were granted in fief. Their owners had an interest in declaring the income from their territory to be lower than it actually was.

In a far-reaching reform, Akbar confiscated all fiefs. To begin with, all public servants were to be paid from the state treasury. The land was then resurveyed, and local officials kept a record of all price and tax data for a period of ten years. From these figures, a ten-year average was calculated for each district, on the basis of which the tax rate was determined. It was to remain the same in the years to come – regardless of whether they were good or bad. Every product was subject to a different tax rate: Those who cultivated indigo had to pay the highest taxes; poppies, which were used to make opium, were next. And sugar cane was taxed twice as much as wheat.

Akbar’s Coinage

The tax reform did not only include the introduction of a uniform system of weights and measures, but also the systematic issuance of coins, which was important because Akbar intended to collect all taxes in cash. In this field, too, he was able to use the preliminary work that had been done by the great organizer Sher Khan. Under his rule, the rupee and the golden mohur had been issued for the first time.

On the occasion of the New Year in AH 1000, i.e. in 1591 according to our calendar, Akbar is said to have had all gold and silver coins of his predecessors withdrawn, melted down and minted new coins with his own name from it.

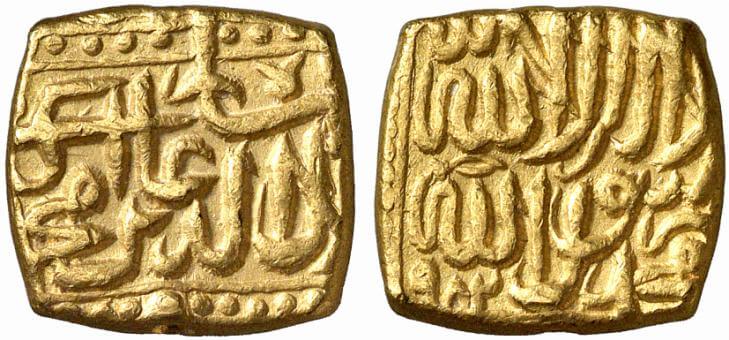

Akbar. Mohur on a square blank, AH 982 (= 1575), name of the mint outside the flan. From The New York Sale XIV (2007), 587.

The heaviest coin was the mohur, a gold coin whose equivalent value was quantified by contemporaries as the total annual yield of two or three acres of land.

Akbar. Half rupee, AH 967 (= 1560), name of the mint outside the flan. From The New York Sale XI (2006), 459.

The most important silver coin was the rupee. Its name was derived from the Sanskrit word “rouppya” meaning silver. It originally consisted of 175 gran of fine silver (1 gran = 0.063 g; i.e. about 11 g) and was worth between 14 and 17 rupees depending on the exchange rate. Sir Thomas Roe, who stayed at the Mughal court from 1615 to 1618, stated the rupee was worth 2.5 English shilling.

The smallest denomination was the copper dam, a coin that had also existed long before Akbar. A rupee was worth 40 dam – which made it quite difficult to do the math: all official revenues and expenditures were calculated in “dam”, which resulted in tremendous figures – after all, one mohur equalled to 560-680 dam. So it’s hardly a surprise that Indian mathematicians became so famous!

Akbar’s coins were issued according to the usual scheme of Muslim coins for 30 years. On one side, gold and silver coins featured the Kalima together with the names of the four successors of the prophet, the caliphs Ali, Umar, Osman and Abu Bakr and their epithets. These varied slightly. They usually read for Abu Bakr: the faithful witness, for Umar: the clement; for Osman: the father of both lights; for Ali: the chosen one.

The function of Muslim coins isn’t limited to the fact that they can be used as money. Just as mentioning the name of the ruler during Friday prayers in the mosque, featuring it on coins is a clear sign of sovereignty that, by dating the pieces, provides precise information as to when and where a particular ruler was recognized. In a society where printed media only circulated slowly within the elite, the bazaar represented the broad public that a new ruler wanted to inform by means of his coins. Even though Muslim coins may seem monotonous to us as they don’t feature anything but words, they are important historical sources.

Contemporary authors give us some details as to how Akbar monitored his coinage. He established a new ministry, which was headed by a minister who worked in the capital. This institution controlled the coin production of all mints of the vast empire. We even know the name of the first minister. He was called Khwaja Abdus Samad and had originally been a calligrapher and painter. Thus, it’s no surprise that Akbar’s coins are of outstanding graphic design.

There is even an archaeological relic of Akbar’s coinage policy. The huge mint of Fatehpur Sikri, where enormous amounts of money could be produced, has survived to this day. In the mint, the metal was first tested by the supervisor of the mint, the darogha. The engravers, among them a well-known artist called Maulana Ali Ahmad, a highly esteemed official with the rank of a yüzbashi (= commander of a hundred), engraved the design directly into the steel die, which was then used to mint the coins.

A New Time

To facilitate the collection of taxes, Akbar replaced the Muslim lunar calendar with a solar calendar. The Arabian moons of the Hijra were replaced with the Persian solar months. This was obviously reflected by his coinage. Akbar introduced a new era, the Ilāhī era, which was based on the solar calendar and whose starting year could not be precisely identified so far.

He also stopped the tradition of featuring the Kalima – the traditional Muslim profession of faith: “There is no deity but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God” – on his coinage. Instead, the legend of his coins read “Allahu Akbar Jalla Jalalhu”, a phrase to which there are several interpretations. The simple translation goes: “God is the greatest, praised be his glory”. However, the Arabic word for “greatest” is the same as Akbar’s name, which is why the inscription could also be translated as: “Akbar is God, praised be his glory.” A message that obviously made many orthodox Muslims sick to their stomachs.

We do not know to which extent Akbar consciously opted for this double meaning when creating the legend.

The End of an Era

The fight for Akbar’s legacy started when he was still alive. His son Jahangir tried to make sure he was to be his heir, and his brash approach turned his father against him. One needs to know that Akbar didn’t have much choice in terms of selecting his successor: his two younger sons were so addicted to alcohol and opium that they died in delirium tremens.

Akbar may have thought a while about transferring his power directly to his beloved grandson Khusrau. But the women interfered. They did not want another dispute over the succession to the throne. Jahangir had the military power and the personal skills. Thus, Akbar’s mother brought about a reconciliation of the generations. Akbar placed his own turban on Jahangir’s head, a gesture that was understood as Akbar officially recognizing Jahangir as his heir.

Akbar died on 15 October 1605. He was buried in a huge mausoleum near Agra.

Did you miss out on the first part of our series on Akbar, the ruler of the Mughal Empire? Here you can read part 1 on how Akbar became the ruler of Delhi and what role his ancestors played in this.

And here you’ll find out why the stars played an important role at the court – and in the coinage – of Akbar’s son, the Mughal emperor Jahangir.

You can find a tour of Fatehpur Sikri, the former capital of Akbar’s empire, on YouTube.