Oh Dear, I Think I’m Becoming a God! Numismatic Testaments to the Consecration of Roman Emperors

by Ursula Kampmann on behalf of Künker

On 31 October 2024, Künker will auction off part 9 of the Dr. W.R. Collection. It presents Roman coins from the period between the civil war of 68/9 and the end of the Severan dynasty. The diverse material illustrates the numismatic traces of the consecration of Roman emperors.

Content

Vae, puto deus fio – oh dear, I think I’m becoming a god, Vespasian is said to have joked when he experienced the first symptoms of the disease that would kill him later. Actually, it might be the case that Suetonius was indulging in anachronism at this point. After all, at the time of Vespasian’s death in 79 AD, it was not as common for members of the imperial family to be deified as it was when Suetonius died in 122. Between the deaths of Augustus and Vespasian, only one emperor was divinized: Claudius. And Seneca’s Apocolocynthosis gives us an idea of how weird his contemporaries found this practice: the title Apocolocynthosis is based on the Roman term for deification (apotheosis), and it refers to something being transformed into a pumpkin.

It was not until Titus and his brother Domitian that the deification of one’s ancestors was systematically used as a political means by the emperors. To establish this practice as a ritual, they took their inspiration from the deification of Augustus.

Demetrius Poliorcetes, 306-283. Tetradrachm, 291/90, Chalcis. Portrait of Demetrius with bull horns. Rv. Image of Poseidon with trident. About extremely fine. Estimate: 1,000 euros. From auction 401 (29/30 October 2024), No. 1152.

Human – Hero – God

But how did the Romans come up with the idea of consecrating an emperor? Well, in ancient times, the barrier between humans and gods was not as insurmountable as it seemed to a devout Christian of the early modern era. In myth, people were constantly becoming gods, or at least heroes, and their fellow citizens paid divine tribute to them after death. Asclepius is one example, as are Heracles and countless city founders. Thus, it was perfectly possible to make this transition. And many Hellenistic rulers took advantage of this by using symbols that had been developed for the worship of gods as a means of self-representation. Demetrius Poliorcetes, for example, presented himself as the son of Poseidon, wearing a blue cloak and having himself depicted with bull horns.

Be it god, hero or human – one’s worship depended on whether believers thought that this individual could help them in everyday-life situations. In this regard, people and communities were rather pragmatic, as we can learn from a hymn the Athenians sang when they brought their new god, Demetrius Poliorcetes, to the Acropolis: “For other gods are either far away, or they do not hear us, or they do not exist, or they pay no attention to us. But you we can see in full presence, not in wood or stone, but in truth. And so we praise you!” Demetrius Poliorcetes had earned divine honors with his military intervention that drove an oligarch government supported by the Macedonians out of Athens and made democracy possible again.

The Romans also did not believe that there was a clear line that separated divine powers from human beings. They kept lares familiares in the lararium. These included Penates and Lares, but also the genius of the pater familias and Manes. These were considered sort of an incarnation of the creative powers of the head of the household and the spirits of all those who had been head of the household before him.

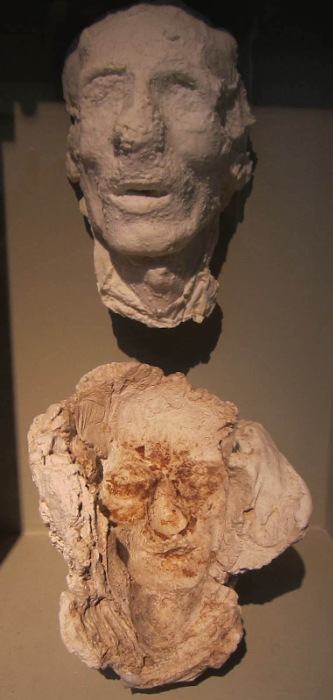

At large (and expensive) funerals, as they were customary among the nobility, the transition from the pater familias to a member of the Manes was clearly demonstrated and even re-enacted. A wax mask was molded from the face of the deceased, and a cast created. This mask played an essential role during the procession that accompanied the corpse to the funeral pyre. The new mask was worn by an actor who dressed and behaved like the deceased. He joined the group of other actors who wore the old death masks of the ancestors kept in the lararium and also participated in the funeral procession. In this way, it was demonstrated that the recently deceased was now one of the ancestors.

By the way, if you are wondering if these naturalistic wax masks have anything to do with Roman portraiture, you are on the right track. Republican mint masters who wanted to depict long-dead ancestors on their coins relied on the lararium to provide engravers with a detailed model.

The Example of Augustus

This ceremony was modified for emperors. After their death, they became the guardians not only of their own family, but of the entire city. Their transition to the heavenly sphere was staged differently, but just as visibly. The crucial moment in this ceremony was their burning at the pyre. At some point, toward the end of the ceremony, an eagle flew out of the fire to carry the soul of the deceased to heaven. At least that is what Senator Numerius Atticus testified on 17 September 14 AD. The Senate then decided on a series of honors for Augustus that elevated the deceased to the status of a god.

A testament to a deliberate damnatio memoriae. Counter-mark of Galba on a 3-assaria bronze coin of Nero from Perinthos in Thrace. Estimate: 50 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3006.

In the post-Flavian period, one could say that after the death of almost every single emperor, the Senate decided whether the deceased was to be accepted among the gods or condemned to oblivion. This was also a way of judging this emperor’s rule.

Faustina the Younger. Denarius, after 176. Rv. Pyre. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 200 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024). No. 3343.

The Pyre

Many issues from the 2nd until the mid-3rd century illustrate such ceremonies. On the obverse, they feature the portrait of the deceased with the title DIVVS or DIVA in front of their name. On the reverse, we can see various motifs. At this point, we will introduce you to the most important ones.

We will begin with the pyre, a depiction that was first used on coins under Antoninus Pius. A pyre – often described with the Latin word rogus – was part of every respectable Roman cremation ceremony, but was especially magnificent at state funerals. In the private sphere, a simple fire was sufficient, in the center of which the stretcher with the decorated corpse was placed. While all the mourners watched as the nearest male relative lit the fire, only the closest family remained until the fire burned down completely. Then the flames were extinguished with wine, and the remaining bones were collected from the ashes and placed in an urn.

Lucius Verus. Denarius, after 169. Rv. Pyre. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 75 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3367.

For emperors, more effort was put into the construction of the pyre. A huge frame with several floors was built from exotic woods. The lowest level, decorated with garlands, contained flammable material to ensure that the fire would generate enough heat to consume not only the imperial corpse but also the votive offerings and the construction itself. The corpse was brought to the next level by means of a small door that can sometimes clearly be seen on coins. Above it were further levels, decorated with statues. A quadriga crowned the pyre of an emperor, a biga that of an empress.

Eagle and Peacock

It is said that there was a cage hidden in the structure, which housed an eagle or a peacock. Ultimately, the fire would burn the cage and the bird flew out of the inferno. There is no written evidence to support this theory, but this is not important. In any case, the eagle became the most common motif on consecration coins.

Marcus Aurelius. Denarius, 180. Rv. Eagle. About extremely fine. Estimate: 60 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3313.

We see the eagle standing or soaring with its wings spread; on some rare coins it carries the figure of the deceased on its back towards the sky.

What is remarkable is that in The Physiologus, a late ancient anthology with strong Christian characteristics from the 4th century, the connection between eagle and eternal live is still maintained. One passage reads as follows: “When the eagle grows old, its wings become heavy and its face weak. What does it do? It seeks a pure spring of water and flies up to the ether of the sun, burning its old feathers and losing the dullness of its eyes; it then descends to the spring, plunges three times into the water and becomes young again.”

Septimius Severus. Denarius, 211. Rv. Eagle on globe. About FDC. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3516.

It seems so obvious that only the eagle was suitable for the task of carrying an emperor into immortality that we no longer think about why this animal was chosen. This probably has to do with oriental concepts, because in the East the eagle was seen as the link between the human and divine worlds. The first ascension by eagle can therefore be traced back to Sumerian Mesopotamia: according to myth, Etana, who ruled after the Flood, tried to ascend to heaven on an eagle during his lifetime, but of course failed.

Domitia. Denarius, 82/3. Rv. Peacock Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 1,250 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3093.

This seems to have been long forgotten in Rome. There, the eagle was associated with the supreme god Iuppiter, and therefore there was no discussion as to what bird was appropriate for the ascension of the empress. While the first deified women were still associated with eagles, by the middle of the 2nd century the peacock had established itself as their travel companion. After all, this bird belonged to Juno.

Iulia Domna. Denarius, 218. Rv. Peacock, with its tail spread. Very fine +. Estimate: 750 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3555.

Juno was part of the Capitoline Triad consisting of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. She was considered the wife of Jupiter, the father of the gods, and was identified with Hera during the Roman imperial period. One of the animals associated with Hera was the peacock, which owed the beautiful blue “eyes” on its tail feathers to her. She had taken them from the many-eyed shepherd Argos to give them to the peacock.

The close connection between the peacock and Hera was transferred to Juno. We can see the peacock on consecration coins with its tail spread or flying.

Faustina the Elder. Dupondius, after 141. Rv. Aeternitas holds a phoenix in her outstretched right hand. About extremely fine. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3265.

Other Motifs

In addition to eagle, peacock, and funeral pyre, there are other motifs associated with the consecration of Roman emperors. One of them is Aeternitas. Since the time of Vespasian, Aeternitas has had her own cult that associated her with the eternal duration of imperial rule. We see Aeternitas either with a phoenix or with the ouroboros, a snake that bites its own tail, forming an endless circle. She is also depicted in a chariot drawn by elephants, a motif that also appears on coins honoring deified members of the imperial family.

Our piece shows Aeternitas according to typical iconography with the phoenix in her outstretched right hand and the circular diadem that, according to the late ancient author Martianus Capella, symbolized eternity.

Antoninus Pius. Denarius, 161. Rv. Altar. Extremely fine. Estimate: 100 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3251.

While the alter can be found on many consecration coins of the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC, imperial temples tend to be reserved for provincial coinage. This may have something to do with the fact that many Roman emperors did not have their own temples in the capital, but were worshipped in the temple of another god.

Commodus. Tarsos / Cilicia. Bronze. Rv. Two neocorate temples, between them the crown of the priest of the imperial cult of the province of Cilicia. Very fine. Estimate: 500 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3412.

However, the neocorate temples that can occasionally be found on issues from the Roman provinces indicate a religious practice very different from that in Rome.

Head of an Athenian local politician, wearing the crown of the priest of the imperial cult. Athens. Museum of the Ancient Agora. Photo: KW.

After all, the title of neokóros did not only entail religious and ceremonial aspects but also came with political rights. If you were a neokóros, the Romans had granted you the right to maintain an imperial temple in your own city. Rarely was a separate temple built for this purpose; the imperial cult was usually practiced in the temple of another god. All the cities of a province regularly gathered there to celebrate a great feast in honor of the emperor. In addition to religious ceremonies and athletic contests, these gathering also provided local politicians with an opportunity to present themselves and to bring problems and concerns to the attention of Roman magistrates.

The right to set up a necorate temple did not require that the emperor in question was already dead and deified. This resulted in the fact that many a provincial city suffered the embarrassment of having a necorate temple in honor of an emperor who was to fall into damnatio memoriae after his death.

Traianus and Divus Traianus Pater. Denarius, 112/3. Rv. Father of Traianus with scepter and patera sitting on the sella curulis to the left. Very fine + / Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 100 euros. From auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3156.

Political Implications

After this brief side trip, let us return to why such a consecration was necessary in the first place. Emperors like Titus, Domitian or Trajan used consecrations to establish their dynasty. Elevating long-dead relatives to the ranks of a god increased the status of your own lineage. A good example of this are all the coins Trajan had minted in honor of his long-deceased father Marcus Ulpius Traianus.

Traianus and his deified fathers. Aureus. Rv. Busts of Divus Nerva and Divus Traianus Pater. Very fine / About very fine. Estimate: 2,500 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3158.

Particularly fascinating is the aureus of Trajan that shows both the bust of his deified adoptive father Nerva and that of his deified biological father.

Marciana. Denarius, 112-117. Rv. Eagle. Very fine. Estimate: 750 euros. From Künker auction 417 (31 October 2024), No. 3171.

Trajan even had his sister Marciana, who died on 29 August 112, consecrated by the Senate.

Did the Romans Believe in the Divinity of the Emperor?

To answer this question, we must set aside what we expect from a religion today. In ancient times, religious ceremonies were not proof of personal faith but a sign of loyalty to a community. It was not important whether a citizen of Ephesos, for example, believed in the greatness of Artemis Ephesia. What mattered was that he took his place in the procession. Neither the Greek nor the Roman gods demanded their believers to be faithful as we would expect it today. They did, however, expect all traditional sacrifices to be made to them. Or rather, people were convinced that the gods would take revenge if they were deprived of the sacrifices and rituals to which they were entitled.

We might find this funny today, but we should remember that the Romans might have found some of our beliefs laughable too.

Bibliography:

- Hans-Joseph Klauck, Die religiöse Umwelt des Urchristentums II. Herrscher- und Kaiserkult, Philosophie, Gnosis. Stuttgart 1996

- Peter n. Schulten, Die Typologie der römischen Konsekrationsprägungen. Frankfurt 1979