What People Used to Pay With in South Africa

By Ursula Kampmann

Coins are only the most recent of the many means of payment used in South Africa. And yet, there is much to be told about the country’s numismatic past. We tell the story of South African means of payment from glass beads to the rand.

Content

To engage in trade, coins weren’t necessary. The seafarers working for Portuguese and Dutch merchants knew that well. It was far more profitable to barter goods, ideally for items that another nation needed or valued.

The Beginnings of a Monetary System

Metal was certainly part of that equation. The Portuguese brought copper and bronze to Africa, importing it in the form of heavy, standardized bracelets called manillas. Such items are said to have been found in South Africa too.

The Beginnings of a Monetary System

Metal was certainly part of that equation. The Portuguese brought copper and bronze to Africa, importing it in the form of heavy, standardized bracelets called manillas. Such items are said to have been found in South Africa too.

Beads were also used in African trade, although we have yet to fully understand how they were employed. Certainly not as mere decorative items appreciated by African trading partners. Instead, the beads formed part of a complex currency system in which different colors and types were accepted for various goods and services by different peoples.

A First Colony at the Cape: The Dutch East India Company (1652–1795)

The Dutch East India Company revolutionized overseas trade. It was no longer just individual merchants joining forces for specific ventures. Now there was a corporation – almost in the modern sense – with salaried employees and the intent to bring as many profitable trade partners as possible under its influence.

One of the VOC’s many trading ships was wrecked in Table Bay, and the survivors were rescued a year later. Their enthusiastic reports of the land’s fertility led company headquarters in Amsterdam to establish a station at the Cape, where food would be produced to supply passing ships – a lucrative enterprise. Jan van Riebeeck landed at the Cape of Good Hope on April 6, 1652, to establish this colony.

Spanish Empire. 8 Reales cob coin, Mexico City. Found on a shipwreck from the 1715 Spanish treasure fleet off Florida’s east coast. From Sedwick Auction 23 (2018), lot 1699.

What did people use to pay at the Cape back then? Most likely the same currency that dominated trade everywhere else at the time: Spanish silver coins of eight reales. We can assume that VOC merchants accepted any currency from passing ships, as long as it was made of good silver or gold. To maintain accurate records, a standardized accounting currency was used called the “Riksdaller,” into which all received and spent coins were converted for bookkeeping and balancing profits and expenses.

Great Britain for the Cape Colony. Counterstamp with the head of George III on a Spanish 8 Reales coin from 1791. From SINCONA Auction 63 (2020), lot 1072.

British Conquest

The Cape Colony was of too much strategic importance not to attract the attention of expansionist Britain. In 1795, the British seized the Dutch colony. Even though a different flag now flew over Cape Town, the problem of cash supply remained pressing. The British used whatever Spanish coins they could get hold of, stamping them with a countermark showing the portrait of George III. It was always stamped onto the neck of the Spanish king.

Great Britain. George III 2 Pence 1797, Soho Mint. Cartwheel coinage. From SINCONA Auction 83 (2023), lot 2055.

We know that the British 2-penny pieces also circulated at the Cape, as they had a local nickname: the very religious Boers called them “devil’s pennies,” since Britannia is depicted with a trident – the same symbol commonly associated with the devil.

Batavian Republic. Half guilder in gold, 1802, Enkhuizen. From Hess-Divo AG Auction 291 (2002), lot 68.

The Batavian Republic

In 1803, during the Napoleonic Wars, the Batavian Republic – aligned with France – briefly regained control of the Cape and Cape Town. As part of a reorganization, the military commander planned a new currency system and a mint to produce it. But minting proved to be too complex, so coins were ordered from Enkhuizen in the Netherlands. Both silver and bronze coins were produced. The gold coin shown here exists because a few rare off-metal strikes in gold were made using the dies of the silver gulden. These were first known as Cape guilders and later referred to in numismatics as “ship guilders” because of the beautiful ship design. These Cape guilders can be considered the first South African coins.

British Rule

Due to a shortage of cash, the British continued using Batavian coins after retaking the Cape. It wasn’t until June 6, 1825, that the governor enacted a law making the British pound the sole legal tender at the Cape – in theory. In practice, troops had to be paid in whatever currency was available, which was usually Spanish 8 reales coins. We know this because the governor complained to the British government that it had set the exchange rate for the 8 reales at 4 shillings 8 pence, a value that was far too low. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that there were enough British coins available to actually pay all soldiers with them.

Griqua Tokens

Griqua refers to communities in southern Africa that emerged from the union of Khoikhoi, Nama, and Boers. Reverend John Campbell of the London Missionary Society used this name for a group comprising Chariguriqua, Basters, Koranna, and Tswana. When he visited a mission station in 1813, founded by two missionaries of the same society, he persuaded the clergy to rename the station from Klaarwater to Griquatown.

The money for Griquatown was also Campbell’s idea. He had it specially made for the mission’s wards. Naturally, these were not real coins but tokens. They were introduced into circulation in 1815 and already withdrawn again in 1817.

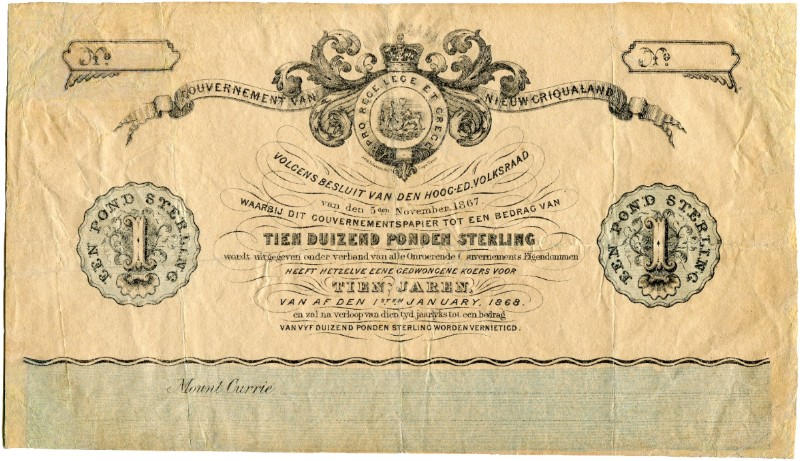

The 1868 banknote from Griqualand belongs to a different context. It was issued for the British colony of Griqualand West, where diamonds had been discovered in 1867. This prompted the British to force the Griqua to cede their territory to the British Empire.

Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek. Burgerspond 1874, die by L. Wyon. Only 695 pieces minted. From Auction SINCONA 80 (2022), No. 3277.

Coins from South African River Gold

In 1872, the Boers elected Reverend Thomas François Burgers as their fourth president. Burgers planned to introduce a national currency and commissioned the private mint R. Heaton & Sons in Birmingham, England, to produce coins that matched British currency in weight and fineness. He is said to have used river gold found at the northern foothills of the Drakensberg Mountains. The settlement of Pilgrim’s Creek was established at the discovery site a year later.

Only a few hundred Burgersponds were struck before the Volksraad (the parliament) prohibited further minting.

A Mint for South Africa

The discovery of gold in 1886 in the area of present-day Johannesburg enabled the South African Republic to mint its own coins in larger quantities. In 1890, the Volksraad authorized the establishment of a national bank, which was also granted the right to issue coins and banknotes. The currency system was based on the British pound, although the first patterns were made at the Berlin Mint.

LINK

The National Bank was built on the northwest corner of Church Square in Pretoria and officially opened on July 6, 1892. Coin production at the mint located there began shortly thereafter. Incidentally, the cornerstone of the National Bank can still be viewed in Pretoria today.

Emergency Currency in the Boer War

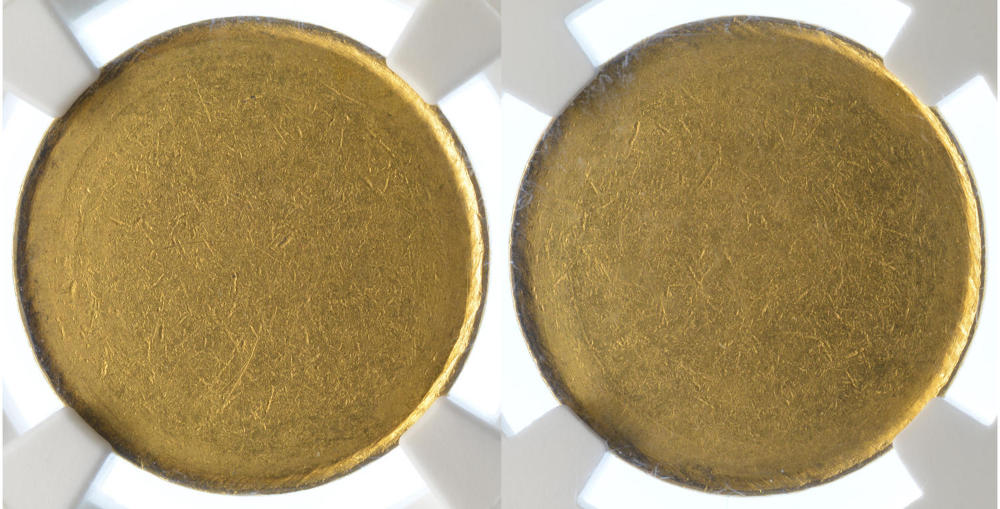

In 1900, British forces captured Pretoria. The mint had already ceased operations by then. Instead, unstruck gold planchets of the same weight as British sovereigns were used. These were referred to as “naked pounds.”

Later, the abandoned mint at Pilgrim’s Rest was put back into service. There, crude dies were cut and an improvised coin press was used to strike Ponds from nearly pure gold with a bullion value of 22 shillings. However, minting proved more difficult than expected: a single set of dies could only strike 986 coins. Furthermore, the coins came too late: by the time they were ready, the Boers had already surrendered to the British.

Under British Rule

With the British takeover came the British monetary system. However, mining companies and bankers pushed for a local mint to avoid the high costs and risks of transporting gold. Other British gold-producing colonies already had their own mints, so why not South Africa? The first request for a local mint dates back to 1902, but only the Pretoria Mint Act of 1919 officially permitted its establishment. Machinery was imported from Britain, and the dies were made by Kruger Gray in London. Naturally, the coins produced in South Africa matched their British counterparts exactly in size, fineness, and denomination.

The first sovereign was struck on October 3, 1923, by the Governor-General, Prince Arthur of Connaught. This marked the beginning of South African coin collecting, as the first proof sets were sold to collectors in the same year.

A Brief Interlude as a Munitions Factory

Just before the outbreak of World War II, the management of the Royal Mint in Pretoria contacted the British Chancellor of the Exchequer to point out that the mint’s spare capacity could be used for munitions production. Manufacturing began in 1938 and ramped up significantly with the outbreak of war.

The Pretoria Mint produced 18- and 25-pound shells, firing pins, and detonators. Coin production became secondary. A total of 14,300 people were hired to produce munitions for the British troops at five different sites.

In the early hours of March 1, 1945, a devastating explosion occurred at the main facility in Pretoria. The disaster claimed the lives of 146 mint employees. The South African Mint did not end munitions production until 1964.

A Decimal Coinage System for South Africa (1961–1964)

With the Balfour Report of 1926, South Africa gained de facto sovereignty, though the South African government only took control of the Pretoria Mint in 1941. In 1961, South Africa left the British Commonwealth and chose to mark this transition with a change in currency. A decimal coinage system was introduced.

Since then, South Africans have paid with Rands and Cents. Today, these coins are no longer made in Pretoria but at the South African Mint in Gateway, Centurion. This new facility was opened in October 1992.