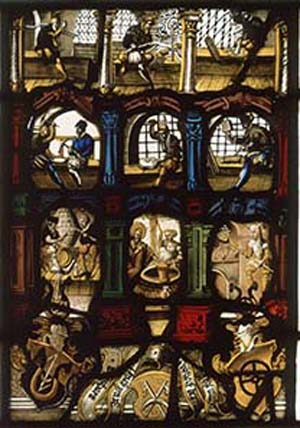

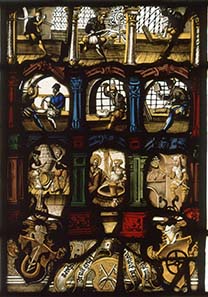

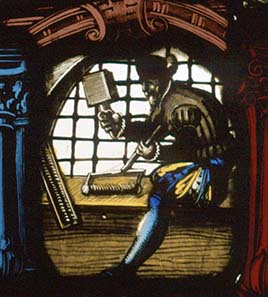

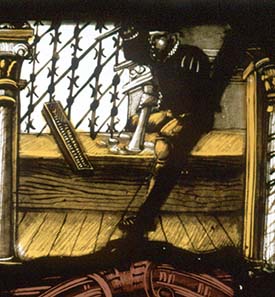

Images from a minting workshop of the 16th century

A pane featuring the coat of arms of Werner Zentgraf, mint master in Schaffhausen

In 1565, the Schaffhausen mint master Werner Zentraf commissioned a pane featuring his coat of arms which is an interesting testimony of the coin production until the present day. Looking at it comes close to a visit of a 16th century mint.

Glass painting from the Schaffhausen mint depicting the operations in a minting workshop. Made in 1565, it is today housed in the Münzkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, and on display in the Bode Museum, room 241.

The commissioner, Werner Zentgraf, is well-known from the records. He was first mentioned as Schaffhausen mint master in 1550 although he was not new to that business. His father had already been a mint master, albeit in neighbouring Constance. As son of the former Constance mint master Jakob Zentgraf, Werner Zentgraf learned his craft from scratch. His advent in Schaffhausen coincides with an era of rich taler production although it was not he that initiated it but Benedikt Stokar (1516-1579) who had rented the mints in Bern, Solothurn and, likewise, Schaffhausen.

Schaffhausen. Reichstaler 1551. Wiel. 683. From auction Münzen und Medaillen AG, Basel 91 (2001), 977.

Benedikt Stokar was a controversial figure since he made good profit when he recoined full-value money into sub-standard one. After Stokar was forced to retire from the money business in 1560 on public bequest, Zentgraf took over his office for a short time and worked as mint master and mint contractor in personal union but his coins, too, were found wanting which lead the persons responsible in Schaffhausen to seriously contemplate appointing Jakob Stampfer from neighbouring Zurich with the coin production for Schaffhausen. But an agreement with famous Stampfer was never reached and Zentgraf stayed although the coin production significantly decreased in the following years: on January 8th, 1563, Zentgraf still had to promise to coin refined silver and silver ingots only but the raw material was hard tom come by because Emperor Ferdinand wanted to force the Confederates to adopt the Imperial mint ordinance.

Thann. Reichstaler 1556. Dav. 9910. From auction Münzen und Medaillen AG, Basel 91 (2001), 704.

Ferdinand established a new mint in its own right in Thann which was supplied in preference with silver. Hence, in Schaffhausen the coin production decreased although Zentgraf did not suffer financially from that limitation. With a letter of recommendation from the Schaffhausen Counsel, he applied for the office of mint master in Thann; after 1564, he worked for Colmar, Breisach and Freiburg – simultaneously, that is, without quitting his office as mint master in Schaffhausen. Business, therefore, was thriving. It is hardly surprising that the successful mint master was able to commission an expensive glass painting which glorified the craft he earned his and his family’s living with.

It is possible to identify on the glass painting many single operations involved in the production of coins although the order is not from top left to bottom right, as we today are used to – instead, the scenes were arranged according to their significance. On bottom left the process of manufacturing coins starts with the melting of the material. In most of the mints that stage had to be supervised by two confidants responsible. From the edict issued in 1567 for Mühlau in Tyrol we know that the mint master and the one administering the office of warden and assayer in personal union had to be present when the alloy was made. Both had a key for the silver vault where the coined money was stored at night. It was their responsibility to ensure that the coins contained the necessary content of silver – that not being the case Werner Zentgraf had been accused of time and again.

The material is melted.

The melting began at 1 or 2 a.m. when the oven was heated up. By adding oxygen the temperature climbed up until the metal’s melting point was reached. It took approximately 4 to 5 hours until the oven was hot enough to melt the silver. That process took place in a big pan a pan watcher looked after. The hot metal was poured in cold moulds and therewith shaped to a bar. On the illustration we see the procedure where an assistant pours the liquid metal into an elongated mould held by a patrician clad in elegant garments, possibly Zentgraf himself.

The ingot is hammered by two assistants.

In the next step, the bar was hammered to produce the level ingot from which the planchets were made. They were hammered first coarsely, then finely. By the way, that technique was already out of date in some mints at the time the painting was made. In Hall / Tyrol the roller coining machine was introduced in1523/4. That apparatus, operated by water, had two rollers with which the raw metal strips were rolled out to an even diameter. It took up to seven operations during which the ingot was alternately annealed and rolled out.

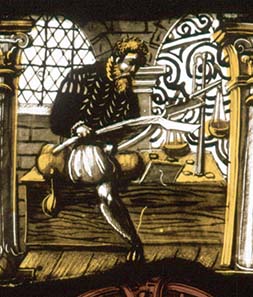

The planchets were weighed piece by piece; the ones too heavy were reduced in size by a metal shears, the ones too light were to be picked out at this point to be melted again.

After even an ingot was produced the planchets were punched out by a hollow punch. The glass painting does not depict that stage because another work step was much more important to the mint master he himself was responsible for: the checking of the minting blanks. In the background one can see the coins scale necessary to check the weight of each planchet. If too heavy, the mint master took the metal shears to clip off a small piece. The significance of that task is made clear by the fact that the person working – it seems safe to call him Werner Zentgraf – sits on a voluminous cushion and wears an elegant costume.

The planchets are crushed: the assistant hits the planchets with a hammer to make them ready for minting.

The man shown below prepares the planchets for minting by levelling them with a hammer. The punching and clipping sometimes resulted in them having sharp edges and an uneven surface which the working step described corrected.

The minting blanks’ edges are smoothened.

Afterwards, the edge of the minting blankets, fixed by a clamp, was smoothened.

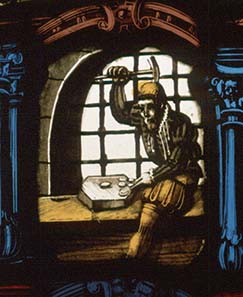

The actual minting.

Then, the actual minting took place. One can see an assistant hitting an overlong obverse die with his hammer; the reverse die is inset in the anvil and hence not visible. On the left-hand side one can discern a counting board which the produced coins were laid in.

The mint’s apprentice anneals the planchets before they are thrown in a mix of water, common salt and spirit of wine.

A step which was important to get visually appealing coins was the sweating. A mix of water, common salt and spirit of wine was prepared that had to boil for half an hour. The planchets, too, were heated. The minting apprentice is depicted wearing his characteristic costume which an impaired observer would most likely associate with a medieval jester. As a matter of fact, similar costumes of minting apprentices have survived to the present day (the Historical Museum Hanover, for example, exhibits an original costume of a minting apprentice). The glass painter therefore, did not use his imagination when painting these peculiar clothes. The thick layers of cloth may have served to shield the apprentice, which anneals the planchets here, from the heat that was usually created in a mint.

The planchets annealed by the apprentice were thrown into the boiling liquid and left there to boil for three minutes while the liquid was stirred continuously. After that, they were taken out and put in a cask, in which they rotated for 15 minutes and cleansed with cold water. To avoid a yellow cast, they were dried on live coal afterwards.

By the way, the commissioner of the coat of arms, Werner Zentgraf, died a destitute man, expelled from his long-time home. The decline started when Werner Zentgraf, already well advanced in years, married young and beautiful Barbara Wissler in 1584; she allegedly had not only free access to the mint but was also devoted to the black arts. Rumours spread in the neighbourhood that she performed magic, searched for treasures and banished ghosts. The only reason why hitherto no measures taken against her husband was his son being married to the daughter of the rich Schaffhausen mayor, Dietegen von Wildenberg. The latter saw to it that Werner Zentgraf was allowed to continue minting albeit only in conjunction with his son. That, however, did not go well. The Zentgraf couple was imprisoned on dishonest practice and lot of debts. In a malefice trial they were sentenced to lifelong imprisonment which, however, was reduced to lifelong exile thanks to the intervention of former friends of Zentgraf and to his son’s good connections. On July 31st, 1594, Werner Zentgraf left Schaffhausen for good and left no further traces in history.

In order to view the glass painting featuring the coat of arms of Werner Zentgraf in the “Interaktiver Katalog des Berliner Münzkabinetts”, click here.

To have a look at other fascinating objects in the Berlin Coin Cabinet, please click here.