Cochin-China – an almost forgotten episode of French history

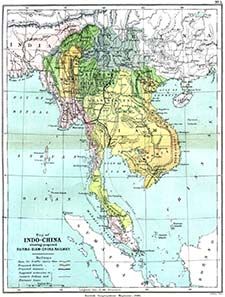

Cochin-China was located in the present-day South quarter of Vietnam (fig. 1). It became a French colony at the end of the 19th century. And this is how it happened:

Map of Indochina with Burma and Siam. Source: Wikipedia.

Since the beginning of the 17th century, the Jesuits had built a lively mission in Indochina. Especially French patres worked in present-day Vietnam. They intended to establish a closer economic connection to their mother country and, therefore, first petitions already reached the French King Louis XIV. In 1787, in the last years before the French Revolution, France – at the intercession of church dignitaries – managed to intervene in disputes over the throne. The bishop of Adran and vicar of Cochin-China established contact to Nguyen Pukh Anh who was about to become founder of the Nguyen Empire with French aid. In return, France gained trade privileges as well as the permission to missionize at will.

Tomb of Emperor Minh Mang. Photo of Pierre Dieule / Source: Wikipedia.

That was a thorn in the Confucian traditionalists’ flesh. Already the son of the first emperor, Minh Mang, strongly opposed any French intervention. On January 6, 1833, he issued an edict prohibiting the Christian faith. He is said to have torn down every church and forced the Christians to trample on the cross as self-evident proof that they had renounced their faith. To which extent that legend was influenced by Catholic circles touting for support at home is hard to tell.

In the following decades the Christian congregation had their share of good and bad times in the Nguyen Empire. Although back home in France the churchmen interposed gruesome stories about horrible martyria and heroic martyrs in their sermons on a regular basis, the motherland was too busy with its own affairs to do anything. That only changed when Napoleon III underwent a major crisis of confidence. He had assumed office to help his country becoming an important big power of great industrial significance. He had promised the people to implement social reforms in order to improve the life of all. With the latter, he wasn’t successful. Hence, at the end of the 50s, his popularity plummeted. What he needed was a quick victory, without much effort but even more impressive. The persecution of Christians at the back of beyond came in useful!

Conquest of Saigon. Illustration of the 19th cent. Source: Wikipedia.

Napoleon III sent a fleet and had Saigon conquered in 1859. In 1862, the emperor of the Nguyen had to surrender the city together with Cochin-China. It took until 1867 to get the entire Cochin-China as safe province under French supremacy. Simultaneously, neighboring Cambodia became a protectorate. France, therefore, had a foothold to China. China, that meant access to the source of silk, tea and luxury goods. China, that promised flourishing trade and maximum profits. France fondly hoped to get thriving business thanks to its new colony.

Cochin-China. Pattern for a piaster 1879. PP. From auction sale Künker June 22, 2011, 4481. Estimate: 10,000 Euros.

During this time our pattern for an own currency for Cochin-China was made. Probably in 1878 the chief die-engraver of the Paris mint, Albert-Désiré Barre whose mark, an anchor, can be found on the reverse on both sides of the mint mark A for Paris, created the dies for a trade coin for Cochin-China. The obverse depicts a figure which is easily identifiable as a close relative of Lady Liberty. Barre definitely got his inspiration for his die from the American Statue of Liberty. France after all collected money since 1875 for a present to the United States of America; until 1886 when the statue, in individual parts, reached New York the French newspapers were full of news about the work of art. It is highly likely that Barr, too, had read the reports and might have regarded the lady with the radiant crown a splendid allegory of the endless opportunities waiting overseas.

The lady, crowned by a wreath of beams and laurel, respectively, sits to the left and holds in her right hand the Roman fasces bundle as symbol of freedom and supports her left elbow on rudder and anchor which stand for the trade. To the left we see rice plants indicative of the exotic atmosphere around here. To the left of her foot the name of the die-engraver BARRE can be read. REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE states the issuing authority. The date of the edition reads as 1879.

The reverse shows an oak and laurel wreath bound together with rice. This being a trade coin is already made clear by the legend: PIASTRE DE COMMERCE (= commercial piaster). To facilitate the circulation of this coin in countries with no French currency the weight (27.215 g) and the fineness (.900) are stated. COCHINCHINE FRANCAISE indicates the French colony. The term ESSAI makes clear that this is a pattern, and indeed this coin did never circulate.

French Indochina. Piaster 1924 A. Extremely fine to brilliant uncirculated. From auction sale Künker June 22, 2011, 4484. Estimate: 400 Euros.

That honor was bestowed only on the second pattern from 1885 with the term COCHINCHINE being changed into INDO-CHINE for the circulating coins. Following this model, money was to be produced for many years to come for the French colony since the situation in Indochina had significantly changed.

French Indochina. Silver-coated bronze medal n. d. (1902/3) by O. Roty on the exhibition of the General Government of French Indochina in Hanoi. From auction sale Künker June 22, 2011, ex 4483.

In the Sino-French War between China and France from April 1884 to April 1885, France had inflicted a defeat on the old protecting power of Indochina, China. France had succeeded in establishing a coherent colonial power consisting of four heterogenous parts: the old colony Cochin-China, whose French inhabitants had a say in the Parisian parliament, and the four protectorates Annam, Tongking, Cambodia and Laos which were governed by French residents.

French Indochina. Silver-coated bronze medal n. d. (1902/3) by A. Patey on the exhibition of the General Government of French Indochina in Hanoi. From auction sale Künker June 22, 2011, 4483. Estimate for both pieces in original case: 250 Euros.

The commerce between colony and motherland were tax-free whereas the French tax tariffs applied for imports of third parties. Indochina was planned as French India but it never became such prosperous as the politicians had hoped for.

In 1931 and 1947, there were French coins minted for Indochina. During the latter time, however, the French were heavily engaged in the one of the bloodiest wars after the World War II…