Women and Finance. An Evolving Image

Wertpapierwelt – Museum of Historical Shares and Bonds has recently opened its new exhibition “Women and Finance. An evolving image”. We publish exclusively parts of the catalog: Read here, why exotic women and ancient goddesses were pictured on security certificates and how role models changed – not only on these papers, but also in real life economy!

Women have always played a key role in the stock exchange landscape. At first this may come as a surprise given the perception that the world of securities is dominated by men, although if you take a look back at shares and bonds of the past, a very different picture emerges: the female touch is everywhere! However, until women were allowed to actively get involved in the financial world, for hundreds of years their role was limited to that of marketing icons.

An impression of the exhibition.

Seen as an embodiment of fertility and prosperity, women for a long time represented the value of a company on its share certificates with both grace and virtue, with the goal of making predominantly male investors feel comfortable entrusting it with their money. While women actively supported the transactions carried out by their husbands or fathers up until the industrial revolution, legal and social norms dictated that they themselves could not usually invest on the stock market. Social change in the 20th century not only gave women the right to their own wealth, but also brought about the necessity of actively managing it, at the very least as some form of retirement fund. The times of women being legally dependent on a “benefactor” are long gone.

The showcases are combined with informative wall charts.

Nowadays, women not only hold the purse strings in many homes, but are also playing a greater role on the political stage – and this is not just with respect to traditional family issues; women are increasingly involved in shaping financial and economic policy. Women have wealth and they are keen to invest it. For some time now, banks have specifically targeted female clients. Numerous studies have been conducted looking into the worldwide distribution of wealth between the sexes, including the differences in male and female attitudes towards investment and the stereotypes associated with this.

Women in real life’s financial world: To this aspect part of the exhibition is dedicated as well.

While there have always been women who took responsibility for their financial situations and left their mark on historical securities, the self-confidence women now show in the financial world and in dealing with investments is new. In times when the appearance of securities was more or less still used as a means of advertising, ancient goddesses, patron saints, allegorical figures and other, usually voluptuous, female figures were commonplace on share certificates. Nowadays it is a case of “curtains up” for women in the financial sector.

Goddesses, patron saints and allegories

Women have been represented on securities in the form of ancient goddesses and patron saints since the early days of public limited companies. When these companies discovered the power of share certificates as marketing tools in the 18th century, women were depicted as an embodiment of fertility, growth and prosperity.

Ceres and Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, were always shown surrounded by an abundance of crops and fruit. These two goddesses were also allegories for the abundant returns that could be gained by investing carefully. The image of Fortuna standing on the globe or with the Wheel of Fortune suggested a security would bring an investor happiness and wealth. Athena, the goddess of wisdom and strategy, was also commonly featured on companies’ certificates. In predominantly catholic countries, it was the Virgin Mary instead of the ancient pagan gods that watched over investors’ capital.

Other images including those of the goddess Industria – often depicted with a hammer, anvil and other tools – and Lady Justice, with her scales, sword and law book symbolizing a company’s law-abiding nature, all featured prominently on certificates issued by the new industrial companies. As individual nation states became more powerful, goddesses increasingly gave way to national symbols, such as Helvetia, Germania or Britannia, who personified their respective countries.

While these images of females were extremely varied in nature, they all shared one thing in common: they were not gentle, delicate figures, but strong, authoritarian women. Looking proudly out from the certificates into the eyes of investors, these aloof, graceful heroines instilled a sense of confidence in investors. However, they were merely symbols: the reality of life for women was very different.

Echoes of the classical antiquity promise success on this security certificate of 1869.

Ceres, the goddess of growth and abundant harvest, was one of the more popular figures on securities certificates in the 19th century and was meant to guarantee a company’s prosperity. Two female figures can be seen on the securities certificates issued by the real estate agent Società Anonima Italiana per Acquisto e Vendita di Beni Immobili in 1869, both of them surrounded by everything that could possibly be attributed to Ceres: a bundle of corn and sickle to the left and the horn of plenty and a harvester to the right – If this doesn’t guarantee success, who knows what will!

The goddess of hunting refers to the merits of a bicycle manufacturer.

In symbolism, arrows represent speed and agility and the bow stands for strength and the instinct to live, two attributes which the designer of the security certificate of the bicycle manufacturer Companhia Ciclista de Portugal made use of. Both emblems are also associated with Diana, the Roman goddess of hunting, who is portrayed on this certificate as a rather scantily dressed beauty in the hope that she would persuade investors to part with their money. However, she is not the only pretty feature in this scene, for really it is the winged wheel of speed – derived from the bicycle of course – which dominates this picture.

The Bank of Athens assembles ancient gods in front of the Acropolis. In 1919 it was their job to push the national economy.

The Banque d’Athènes adorned its security certificate from 1919 with the tutelary goddess and patron deity of the city that was named after her. Athena is also the Greek goddess of wisdom, arts and crafts, as well as strategy. Fortified with a helmet and breast plate, she protects the city, which is represented by the figure sitting before her. Hermes, the god of tradespeople, and a female character similar to that of Lady Justice with her blindfold, greet them in a friendly manner, indicating that the company will also flourish with their support.

Housewives, workers and consumers

Women’s role on securities began to change in the second half of the 19th century: for the first time, they were portrayed as housewives, consumers, and workers. Women who were active in the real world now replaced these idealized figures that embodied hope and belief.

Realistic representations of women clearly showed the hardworking and exemplary housewife going about her daily business, running her household and cleaning the home. She took responsibility for shopping for the family, and – at least in the lower social classes – contributed to the family’s livelihood. Above all, the image of a women in her home by the stove, surrounded by children and bubbling pans, reflected the clichés of the time. Caring mothers and indeed female members of the bourgeoisie, who dedicate their lives to the muses and the fine arts, reflect an idealized world view. But the money needed to finance such a world still largely remained in the hands of male investors.

However, at a time when for most middle-class women paid work was the exception rather than the rule, securities were already beginning to feature images of women at work. Portrayed as farmers, harvesters or textile workers, the women on share certificates still performed traditionally female activities. Yet still this was a somewhat glorified representation, with women often dressed in traditional garments.

This began to change towards the turn of the century as female factory workers were portrayed more realistically working with machines. As such, shareholders, who generally came from a different social class, could rather patronizingly view themselves as “employers”, who provided these women with an income. Ultimately though, it was more to do with the fact that shareholders were profiting from women’s hard work. Working conditions and even equal pay were a long way off from being considered an issue. As workers’ representative bodies became more important and a greater proportion of the population began to own shares, these representations of women again disappeared from securities certificates.

When the first major department stores began to appear in the middle of the 19th century, consumerism was still seen as immoral. The temptation of consumer goods was considered a threat to the traditional, thrifty housewife. Once many of these temples of consumerism became limited companies around fifty years later, shareholders were also keen to make a profit from those giving into consumer temptation. Every time the cash registers in department stores rang and consumer goods were sold, investors saw their investment grow. As such, female consumers are shown on certificates indulging in goods and full of the joys of life. However, the money that most women had at their disposal was only housekeeping money and gifts from their husbands. These images of women were thus designed to encourage shareholders to offer their wives and daughters such lives.

A housewife on a certificate issued by the Hungarian ‘Household’ General Consumer Cooperative.

The certificate issued by the Hungarian “Household” General Consumer Cooperative leaves no doubt as to who was in charge of running the home and everyday shopping at the beginning of the twentieth century. Completely in the style of naïve art, a proud housewife stands on the steps of her garden with an apron, bowl and wooden spoon. The first agricultural cooperatives in Hungary were created in the 1890s. Over time, the consumer cooperatives of the industrial workers and city residents merged to form a cooperative society.

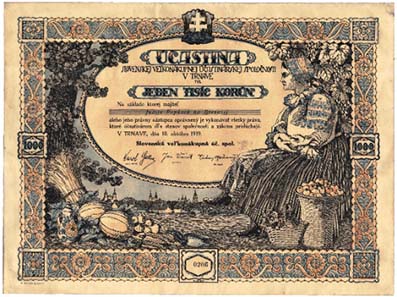

In 1919 Slovakians observed traditional values.

The founders shares issued in 1919 by this Slovakian wholesaler in Trnava is based on traditional values. The down-to-earth farmer’s wife is shown wearing the national dress sitting in the field with her baskets full of local agricultural produce, while in the background you can see a silhouette of Bratislava’s skyline. This typical Slovakian image was used as an advertisement by the company, which enabled smaller merchants from the west of the country to buy in bulk.

Exotic and erotic

The Belle Époque saw wild beauties and seductive eastern women on securities, enticing investors with their exotic appearance. In real life, however, social conventions of the time dictated that women still had to dress conservatively in long, concealing dresses. Since the start of the 20th century, bare-breasted maidens have adorned securities from all sorts of companies. Share certificates featuring exposed breasts, or a naked leg, for example, were all designed to enchant and seduce investors.

As long ago as the 19th century, more and more companies were commissioning famous artists to design their security certificates. This was aimed not only at demonstrating a company’s cultural relevance, but also at giving the security a contemporary feel. Colonial companies in the imperial age decorated their certificates with half-naked women, for example, effortlessly carrying baskets and water jugs: a reflection perhaps of the cheap labor used by the company to maximize value for shareholders.

Scantily-clad, foreign women were a stark contrast to the daily lives of investors, while the accompanying images of agriculture or a company’s product highlighted the link to labor and productivity. But this may somewhat conceal the fact that certificates were largely designed to be pleasing on the eyes of investors.

As the age of Victorian prudishness drew to an end, giving way to the era of Art Nouveau, the way women were represented on securities veered increasingly towards the erotic. Whether banks, printing houses, electricity companies or builders merchants, they all placed great emphasis on female beauty, irrespective of whether this had any link to the company’s field of business. Images of women on security certificates no longer merely played a decorative and ornamental role designed to appeal to male investors – they had become objects of lust.

The slogan “sex sells” applied when it came to marketing many items, including securities certificates, until well into the 20th century. Or perhaps the idea was to suggest that owning shares – that is to say, money – made shareholders equally desirable and sexy? After all, the target group of companies issuing such certificates was still predominantly male.

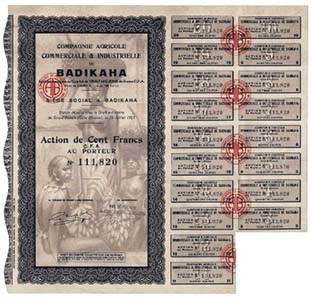

Those West-African women have to convince the share holders of the fertility of their country showing a lot of sex appeal.

This share certificate issued by Compagnie Agricole Commerciale & Industrielle de Badikaha in 1927 shows three West-African women, depicting them as majestic, bare-breasted wild females. Their erotic appearance not only hints at their fertility, but also the fertility of the soil they are tending. The women proudly carry the fruits they have harvested home on their heads.

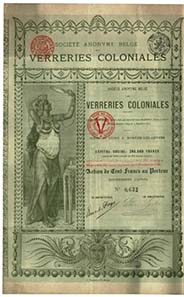

Manufacturers of glass pearls use exotic images as well to attract investors.

In 1898, the Société Anonyme Belges des Verreries Coloniales was already drawing on erotic images and clichés to attract investors. The company specialized in the manufacture of glass pearls, which also used to be used by Europeans as a means of payment in the colonies. The foreign beauty pictured on the share certificate from 1898 is adorned with an abundance of these pearls. In prudish Victorian Europe, the openly exposed legs and breasts are likely to have stirred – male – imaginations more than the company’s products.

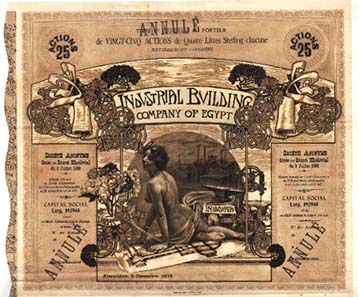

An Egyptian Building Company puts a desirable naked woman even in front of an industrial landscape.

You would never have expected quite so much sex appeal as appeared in 1908 on this share certificate issued by an Egyptian construction company, in this case the Industrial Building Company of Egypt, which features a desirable naked woman sitting casually on a set of architect’s plans. However, the use of the words “Labor” and “Industria” together with the chimney stacks in the foreground show that the company works hard for its shareholders.

Businesswomen, investors and heiresses

By the 19th century, women were beginning to move from paper into the real economy as investors and founders of companies. Certificates held by early female shareholders show that women have always been interested in financial investments. While the role of independent businesswomen and female entrepreneurs in the past was more of a minor one, security certificates can trace back the impact that they did have.

In both the liberal Netherland and the United States, there were securities over two hundred years ago that prove middle-class women were in charge of their own finances. Many covered their financial needs by using their – often inherited – land as collateral for loans. Heiresses also had the opportunity to have a career of their own. While their husbands were alive, many were often involved, both operationally and financially, in building up a company before taking responsibility for it after their partner’s death. It was often the case that these widows then led these companies to real success, as was the case with Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin, for example.

The ownership of shares was always passed on to future generations as inheritances. Registrations or transfers of share certificates showed the paths that capital took: from fathers to daughters, from husbands to wives. Nevertheless, women in the 19th century also invested their assets in public limited companies on their own initiative. These investors were often widows, who under law were allowed their own assets, but about whom there is little information available today. Philanthropic companies and projects that specifically took women’s needs into account received financial backing from female investors at an early stage. However, commercial companies waited until well into the second half of the 20th century before targeting women as shareholders.

If a woman wanted to become an independent entrepreneur, however, there were many obstacles along the way. Outside of homemaking and parenting, there was almost no education that was viewed as suitable for a woman. It was not until the 1870s that European universities began admitting women.

At around the same time in England, the women’s movement was bringing about changes to the law, under which the assets of married women no longer went to the husband and these women were able to conclude contracts independently. However, women were only allowed to take out loans with the consent of their husband or a guardian – in Germany, women needed permission from their husband to open a bank account until the end of the 1960s.

Nevertheless, examples such as Madame Tussaud through to today’s modern female managers, show that ambitious, decisive, disciplined women with initiative will always manage to build up their own companies and make it to the top of the world’s largest companies.

And long may it continue!

Here you do not see the woman on the certificate, because she is behind the scenes: In 1805 Barbe-Nicole Clicquot decided to run one of France’s biggest champagne houses.

“How sweet and airy sparkles the bubble / Of widow Clicko in the glass” wrote poet Wilhelm Busch in 1872 in his story about pious Helen. The international success of the Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin champagne house stretches back to 1805, when the then 27-year-old Barbe-Nicole Clicquot (née Ponsardin) decided to continue running the company on her own after the death of her husband. As the first woman to run a champagne house, she employed innovative ideas and a good business brain to make her brand of champagne known throughout the world. She ran the company for over 50 years. Her memory still lives on today in the form of the Prix Veuve Clicquot, a prize awarded in many countries to recognize female entrepreneur of the year.

Madame Tussauds and its waxworks were converted to a public limited company in 1926.

Madame Tussauds, the world famous tourist attraction, still bears the name of its founder. Having grown up in Berne in the household of Dr Curtius, a wax sculptor, Marie Grosholtz accompanied him to Paris, where he trained her in the art and subsequently bequeathed her his collection of wax figures. After the upheaval of the French Revolution, Marie Tussaud, as she was now known, left her husband and one of her sons back in Paris so that she could take her touring exhibition to England to earn some money. Starting in 1802 she spent 33 years touring the UK before opening her first permanent exhibition in London in 1835. In 1926, her descendants converted her waxworks to a public limited company.

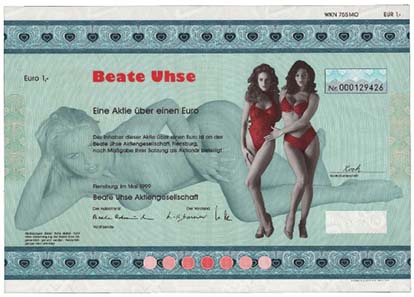

Beate Uhse floated her sex shop on the Frankfurt stock Exchange at the age of 80. On the share certificate you can see only her signature.

Beate Uhse opened her first “specialist shop for marital hygiene and specialist literature” in Flensburg in 1962, or as the press called it “the world’s first sex shop”. This followed years of building up a mail-order business and the distribution of pamphlets that explained the secrets of contraception to women who were in dire need of such information after the Second World War. In 1999, at the age of 80, she floated the market-leader in sex aids on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange before withdrawing from business life. As the chair of the group’s supervisory board, she signed the share certificate using her second married name, Beate Rotermund.

All texts are by Dagmar Schöning and Thomas Fenner. Text and pictures are taken from the catalog of the exhibition.

Published in CoinsWeekly by courtesy of Wertpapierwelt.

You will find more information on the exhibition on this site.