Charles Borromeo –The Saint of the Counter-Reformation, Part 1

translated by Annika Backe

In addition to the founder of the Jesuits, Ignatius of Loyola, Saint Charles Borromeo is probably the saint mentioned most often with regards to the exemplary implementation of the church reform after the Council of Trent. Here we tell his story as mirrored in the numismatic testimonies.

St. Charles Borromeo clad in the attire of a cardinal. Photo: UK.

Efforts to reform the Catholic Church

On December 2, 1560, a bull left the papal court. It dealt with the major concern of Pope Pius IV: the church reform.

The Calvinists in France worried him. The Pope feared that French King Charles IX, who was known for his Huguenot leanings, could copy his English brother and found a proprietary French church.

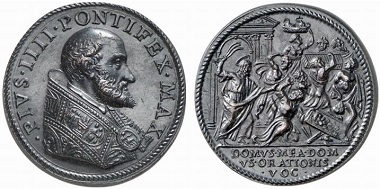

Pius IV (1559-1565). Medal. Rv. Jesus expels the traders from the temple. – This parable of the Counter-Reformation demands a return to a more simple church, in which offices and the accompanying benefices aren’t the center of attention. From Heidelberger Münzhandlung Herbert Grün sale 48 (2007), 721.

To prevent this, it thus became necessary to promote the church reform. There was still plenty of reason to criticize the institutional church. Although the first Council of Trent had met already 15 years before, the reform of the church had been stuck in its early stages.

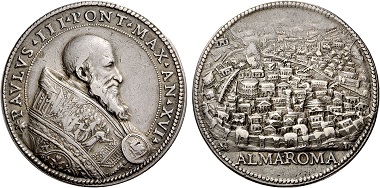

Paul III (1534-1549). Scudo d’oro, Parma. From Künker sale 207 (2012), 6222.

The opening of the Council of Trent

At that time Pope Paul III summoned the council as a concession to Emperor Charles V. It wasn’t a pleasure to the Supreme Pastor. But Charles sought papal help to re-integrate the Protestants into the church through concessions.

Paul remained skeptical, for he didn’t want to jeopardize the still young position as successor to Petri over some council, on the one hand; on the other hand, critics within the church already gave him hell in a particularly delicate matter. It was about the patronage system at the papal court, which constituted the basis of the power for every pope: Everybody who wanted an office needed a patron or a lot of money to buy himself the support of a powerful man.

Paul III (1534-1549). Silver medal no date (1550) on the Holy Year. From Nomos sale 5 (2011), 25.

Roman sleaze

The patronage system was the core of Italy’s powerful dynasties competing for the rise in the churchly hierarchy. The higher one of them had climbed the more benefices he could accumulate. And a benefice was as good as cash. A benefice was a spiritual office whose holder was rewarded with certain revenues. It wasn’t required to be present in person. The Pope was happy to grant a dispensation (against payment) that enabled the beneficiary to send a deputy who would represent him in this position for a small fee. The remaining duties were passed on to the official beneficiary.

And, of course, as soon as you had made it into this position, you could also give benefices to your family members and clients. The same here: The higher your position, the more – and the more lucrative – the benefices you could allocate.

Bully’s eye in this system was the office of the Pope, who provided his relatives with profitable posts at the head of the church hierarchy even when he had already served his term of office.

Christoforo Madruzzo. Medal by Laurentius Parmensius. From Rauch (Summer Sale 2010), 2206.

A half-hearted reform

And this system was put under consideration as the first thing at the Council. Christoforo Madruzzo was Prince-Bishop of Trento from 1539 to 1567. In this capacity, he opened the Council of Trent in 1545. Some reformist clerics demanded that the owner of a benefice should be compelled to reside in the very place of his benefice. This would have meant that each cleric could have been given only one benefice, a decisive leap forward in terms of the pastoral care’s quality. Considering his possibilities restricted, the Pope blocked.

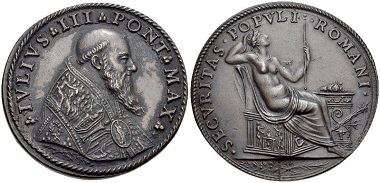

Julius III (1550-1555). Medal 1554/5. From Classical Numismatic Group Electronic Auction 210 (2009), 369.

The ‘Innocent scandal’

The story of a particularly foul testimony to papal favoritism proves that the reasons for the Pope to do this were no altruistic ones.

It was all about Innocenzo (= the Innocent), a juvenile from the most humble background. His good looks caught the eye of Cardinal Del Monte, later to be Pope. He took him to his court –as a toy-boy, rumor had it. In order to give him an official position in the household, the brother of Cardinal Del Monte adopted him.

When the Cardinal was elevated to become Pope, he made Innocenzo – who was 17 at the time – a cardinal, too. Innocenzo, though, didn’t meet the requirements of this position, for he wasn’t able to learn the ropes. Nevertheless, the Pope lent him the official title of ‘Cardinal Nephew’. In this function, Innocent should have been responsible for conducting the papal correspondence.

Julius III (1550-1555). Medal. From Classical Numismatic Group Electronic Auction 210 (2009), 370.

His mere existence was a scandal in Italy. He was accused and convicted of raping two women. He’s said to have killed two men for insulting him. In fact, for this he was imprisoned after his patron had died.

No reform under Julius III

And so, after two years, the Council more or less had come to nothing. It was planned that be resumed under Julius III in 1551. But in spite of his good will, the only result of it was that the Protestants were alienated by the freshly formulated doctrines of the Catholic Church so much that an agreement was no longer possible.

Even the publication of the reform proposals, prepared by a deputation for Julius III, was repeatedly delayed after the completion of the document. And when the reformist Pope died in 1555, they were shelved once and for all.

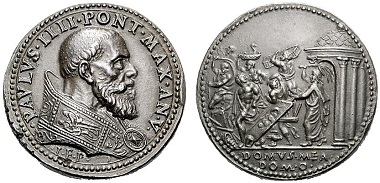

Paul IV (1555-1559). 19th century restitution medal modeled on a 1559 medal by Gianfederico Bonzagni from 1559. Rv. Jesus expels the traders from the temple. From Rauch sale 89 (2011), 2814.

Paul IV

The reformists pinned all their hopes on the Pope who was elected next. They were disappointed. Paul IV used force to better the people. What did not fit into his philosophy, should no longer be read. Thus, shortly before his death in 1559, he introduced the notorious Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the book through which the Catholics learned which books the Pope forbade them to read, in order to not put their souls at risk. What the people of Rome thought about this becomes clear by what they did when they learned of the death of this unyielding man: They stormed the Inquisition’s prison and knocked over the statue of the Pope.

Pius IV

His successor was an agreeable member of the family of the Medici: As Pope Pius IV, Giovanni Angelo of Medici rose to the Holy See in 1560, and he immediately began to revive the Council of Trent. His personal friend was his young nephew, who was to be known throughout the Catholic world under the name of Charles Borromeo.

In the second part of this series you can read how quickly Charles made a career in this corrupt church. And the third part is available here.