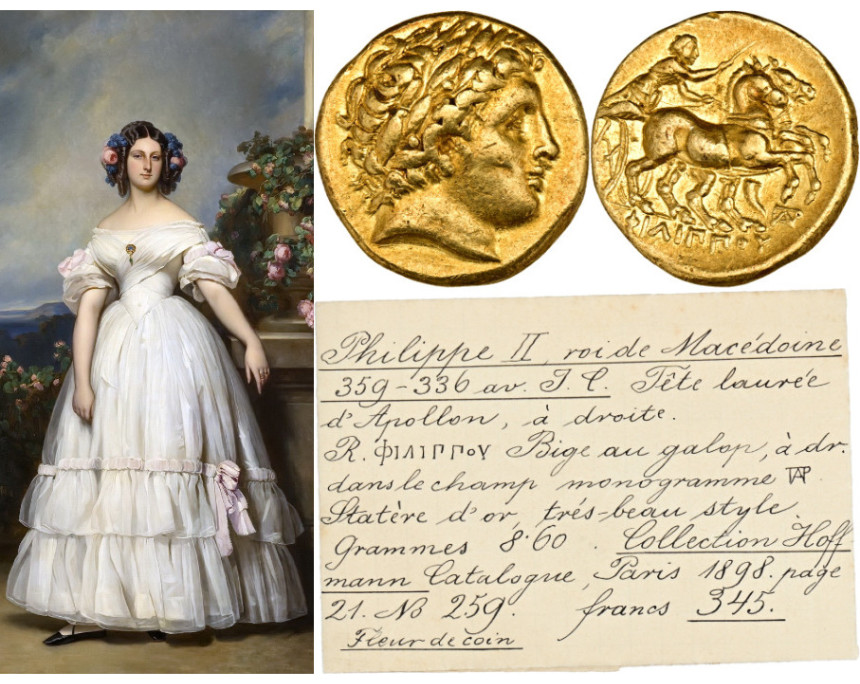

Clémentine d’Orléans: Extraordinary Woman and Coin Collector

by Ursula Kampmann on behalf of Künker

Few women have left such a decisive mark on the history of 19th-century Europe as Cleméntine d’Orléans, and yet it was not until 2007 that her life was honored with a biography. Künker is delighted to be able to offer a coin collection that once belonged to this woman.

Content

On 3 June 1817, Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily, wife of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, gave birth to her sixth of what would eventually be ten children: a daughter, elaborately christened Marie Clémentine Léopoldine Caroline Clotilde. At the time of her birth, Louis Philippe was far from a contender for the throne. He was serving as general in the French army and was a loyal supporter of the recently restored Bourbons Louis XVIII and Charles X.

There may have been a slight uneasiness, however, as Louis Philippe’s father – an enthusiastic supporter of the Enlightenment – had supported the French Revolution under the name Philippe Égalité. Although, like many others, he had died on the guillotine during the Reign of Terror, he had raised his son according to the ideals of a new, enlightened and economically strong bourgeoisie. Maybe this is what gave Louis Philippe his uncanny ability to read the signs of the times. He traveled to England and the United States and had discussions with (for that time) progressive politicians like George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. At the same time, though, he also maintained strong ties to important banking houses such as Rothschild and Laffitte.

Louis Philippe perfectly knew how to handle money, including his own. He used the most modern investment methods to expand the already enormous family fortune. Even before his accession to the throne, Louis Philippe was one of the wealthiest men in France. As early as 1821, his fortune was estimated at around 8 million francs – and it was to increase considerably.

A Modern Upbringing for the Children

Louis Philippe also shared the upbringing ideals of the French bourgeoisie. The fact that family life should be loving and involve plenty of contact between parents and children was a given for him. Clémentine – or Titine, as she was affectionately called by her siblings – experienced an almost normal upbringing. They dined and celebrated as a family; they traveled together to the countryside, where Titine and her siblings gallivanted in parks and swam in ponds.

Naturally, each of the children also received an excellent education. For the girls, this meant a troupe of governesses and tutors who taught them embroidery and dancing, etiquette and conversation, and, of course, the mastery of a musical instrument (the harp, in Clémentine’s case) that was inevitably expected of every little girl. The syllabus was rounded off by various languages as well as religious education personally provided by Maman. The father was also involved in educating his children. He had some experience, after all, having taught French to make ends meet during his years of exile. Louis Philippe taught his children history and geography using memorabilia from the family estate. Clémentine completed her education by embarking on the Grand Tour, which was more usual for young men at the time. She journeyed to the mountains of Switzerland and beheld the wonders of Italy.

Whether Clémentine had already begun to take an interest in coins at this time cannot be known for sure. But we do know that she was not the only family member interested in numismatics. Among her close relatives were several prominent collectors. The most well-known of these today is Henri, Duke of Aumale, who assembled such an extensive collection of paintings and art objects that his coin collection tends to be forgotten. Clémentine’s eldest son Philipp was also an ambitious numismatist. He published works on oriental numismatics, and his collection was auctioned off by the Leo Hamburger auction house in Frankfurt in 1928.

Although, in the 19th century, it was widely considered good form for an educated man to collect at least a few coins, this was not really the case for women. And the reason for this probably was not even a lack of interest: most women just did not have the necessary financial means to purchase coins. But this was not the case for Clémentine. She had one of the largest fortunes in Europe.

Old Nobility, New Funds

Clémentine had learned from her father how to handle money: how to invest it, grow it, and ultimately use it to achieve one’s political goals. Her father Louis Philippe was masterful at this, after all.

Bear in mind: when Charles X was overthrown by a bourgeois revolution on 28 July 1830, the rebels did not dare confront Europe with a new republic. Instead, parliament elected (!) a “compromise king” who represented bourgeois ideals but still had enough royal flair to function as king. This compromise king was Clémentine’s father, Louis Philippe.

The implications of this are best summarized in a scathing comment made by Prussian King Frederick William IV when, in a similar situation 18 years later, he refused to accept the title of German Emperor: “Any German nobleman with a cross or line in his coat of arms is a hundred times too worthy to accept such a diadem, forged from the dirt and sediment of revolution, treachery and high treason.”

Let that sink in and consider how the old high nobility must have felt about the children of a king who had done exactly that. In the past, the sons and daughters of French kings had married heirs to the throne of the most important royal houses in Europe. Louis Philippe had no choice but to seriously reconsider the marriage plans for his offspring. Of all the daughters of the Citizen King, only one became a queen. And even then, she married Leopold I, who only acceded to the Belgian throne following the revolution of 1830.

Clémentine, who was strong-willed and did not conform to the beauty standards of her time, took a particularly long time to find a suitable husband. She eventually married 1843 – at the (for that time) ripe old age of 26.

One of Europe’s Wealthiest Women

As her husband, she chose the slightly younger Prince August of Saxe-Coburg-Koháry. On his father’s side, he belonged to the most well-connected noble house, and he could expect to inherit a vast fortune from his mother’s side. Even if not for Clémentine herself, this presented great potential at least for her descendants.

Was there another aspect that made this marriage attractive to Clémentine? We can only guess based on a letter written by her mother shortly after the wedding: “Il [meaning the groom] dit toujours Amen à tout ce qu’elle veut.” (= he says yes to everything she wants).

August gave Clémentine free reign to handle and expand the family fortune. Her dowry had amounted to one million francs. Added to this were her trousseau and wedding gifts, worth a total of 300,000 francs. Her husband received an annual allowance of 100,000 francs and Clémentine herself 50,000 francs. A lot of money, but by no means a large fortune. With clever investments, however, Clémentine turned it into one.

Imagine the practicalities: thanks to her ties to many leading European families, Clémentine was able to obtain reliable insider information. She likely utilized this knowledge to mercilessly game the stock market and rake in huge sums.

The mother of Clémentine’s husband, August, died in 1861. He inherited most of her property, including estates, forests, mines and factories on more than 150,000 hectares in Lower Austria, Hungary and present-day Slovakia. This inheritance catapulted Clémentine into a completely different league financially.

Ferdinand I. Large gold medal commemorating the completion of the railroad line between Yambol and Burgas. 110 ducats, 1890. From the estate of Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria. Estimate: 50,000 euros. Hammer price: 170,000 euros. From Künker auction 395 (13-15 November), No. 323.

The Rise of the Saxe-Coburg-Koháry Family

Clémentine had thus become one of the wealthiest, best-connected, most intelligent and best-educated women in Europe. And she used all her formidable skills to ensure her children were positioned in a manner that offered them the prospect of ruling over Europe. Clémentine had meanwhile learned that, when a dynasty came to an end, it was no longer the rulers who decided who should become king. In the 19th century, this matter had been taken over by the citizens of the newly emerging nation states. They would contact potential candidates, hear what they had to offer and ultimately choose whoever promised the best diplomatic connections and the largest infrastructure investments. And money was something the Saxe-Coburg-Koháry family had plenty of. The sons thus had to marry suitably to ensure they would be positioned as potential candidates for the throne.

It suddenly becomes clear why the eldest son, Philipp, had married the eldest daughter of King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold had no male heir, which meant the question of the throne would arise after his death. But it never came to that; the marriage between Philipp and Louise was dreadfully unhappy and they divorced in 1906 – three years prior to Leopold’s death.

The situation was similar for Clémentine’s second-eldest son, Ludwig August. He married Leopoldina of Brazil, whose father, Dom Pedro II, also had no male heir. In this case, however, the imperial father-in-law was dethroned in a military coup.

The youngest son, Ferdinand I, succeeded where his brothers had failed – and it did not even require a marriage. The Bulgarians came knocking and requested that Ferdinand accede to the throne. We do not know what promises they received in return; we only know that Clémentine’s immense fortune was crucial to the expansion of the Bulgarian rail network. We reported on this in detail last year in our article about Tsar Ferdinand I and the railroad.

Collecting Coins: A Meaningful Pastime for the Retired

Clémentine was born on 3 June 1817. She died in Vienna on 16 February 1907, having reached the impressive age of 89. Like many people who have led a full life, she too sought interesting pastimes to keep her occupied in her old age. One of these was coin collecting. The Künker auction house is proud to offer the coin collection of this interested and educated Princess at auction 416, where it is sold as lot 2166.

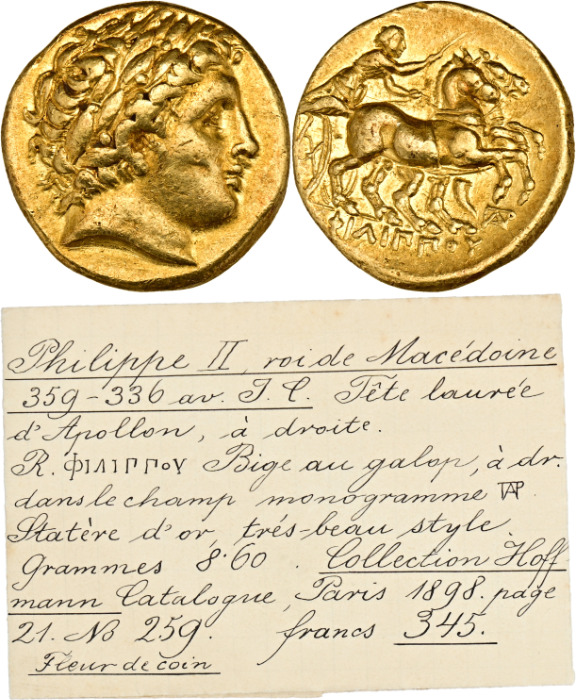

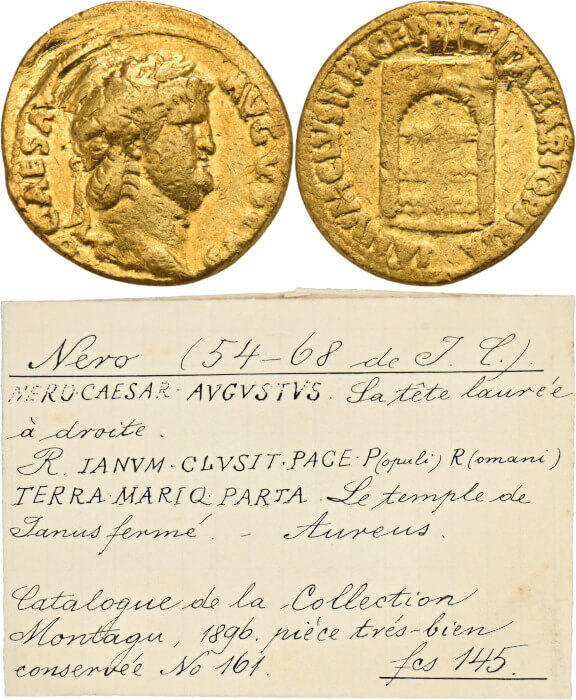

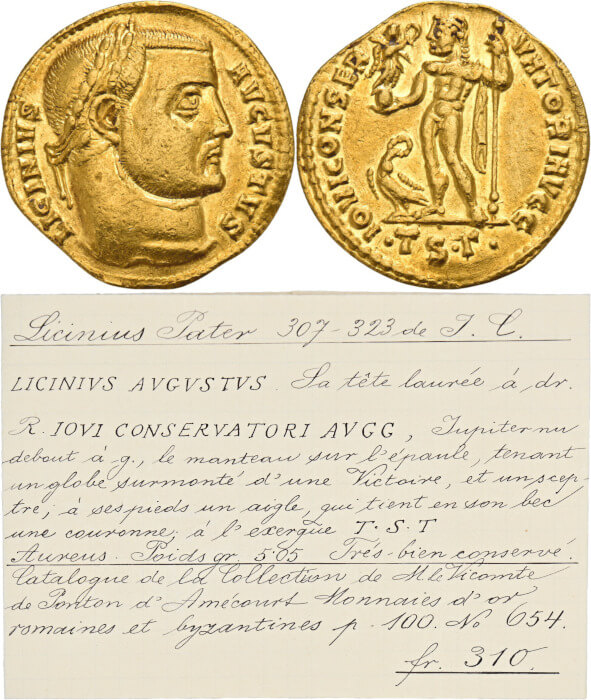

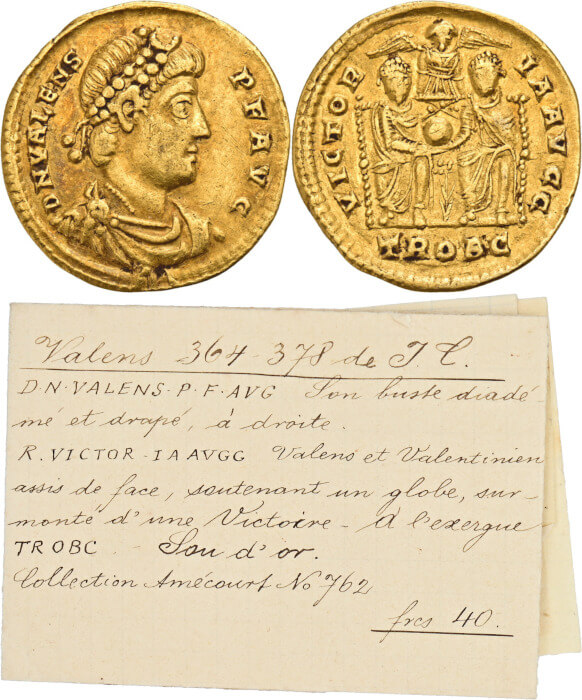

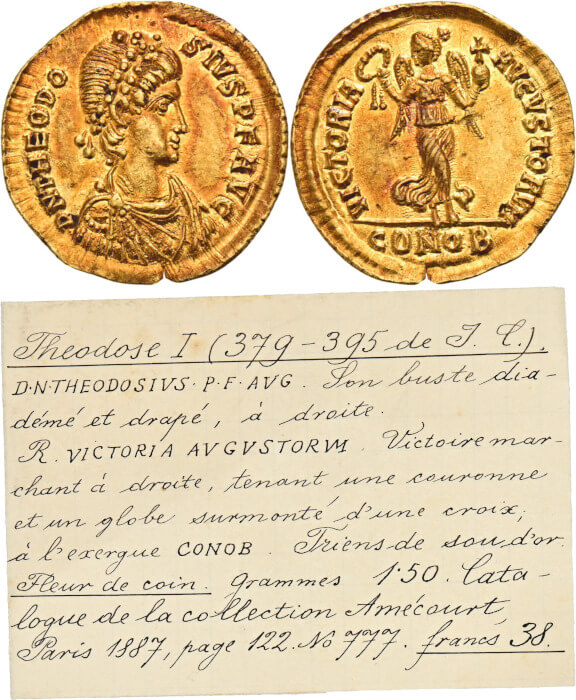

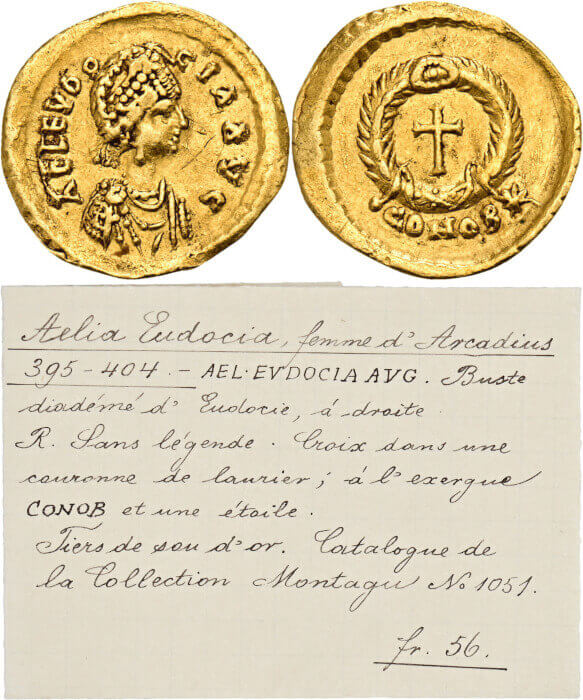

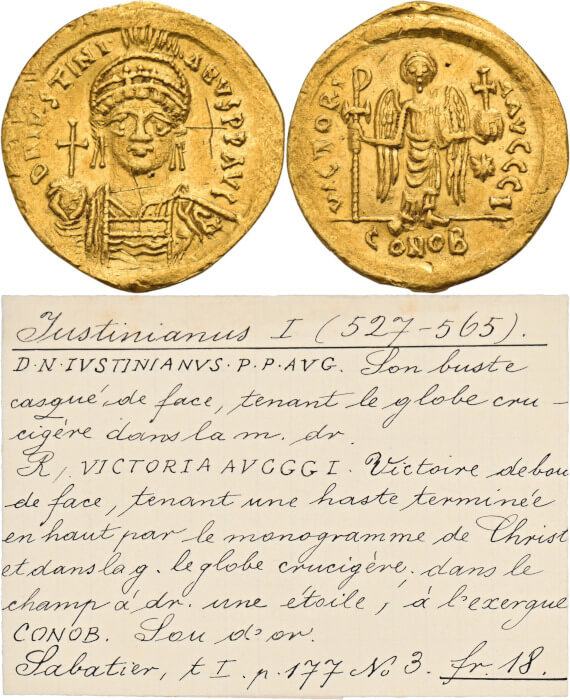

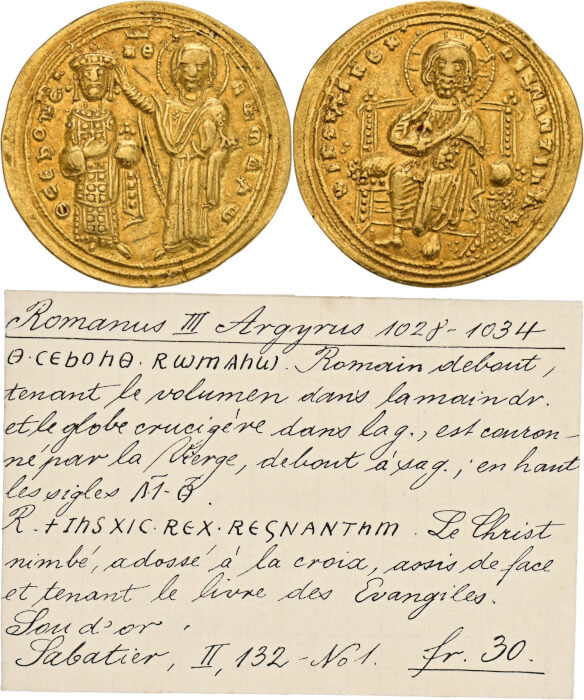

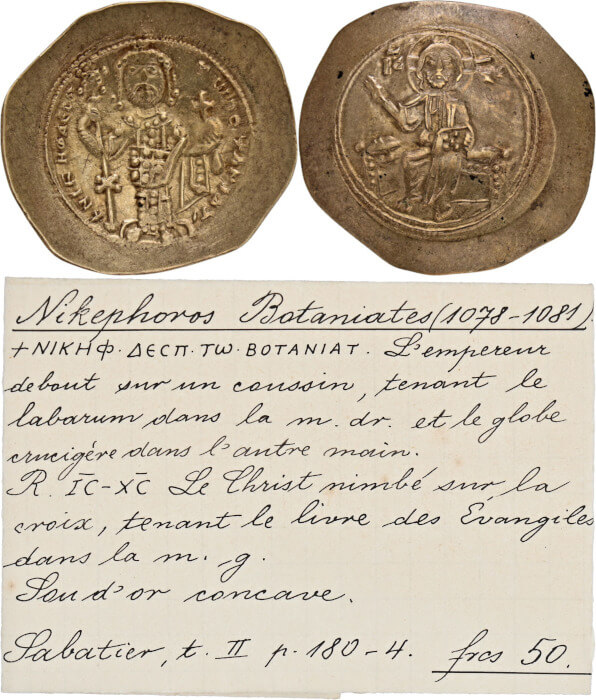

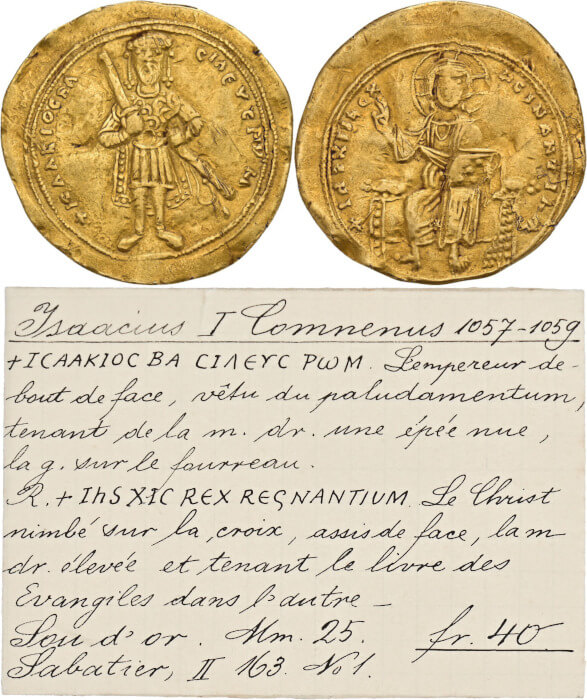

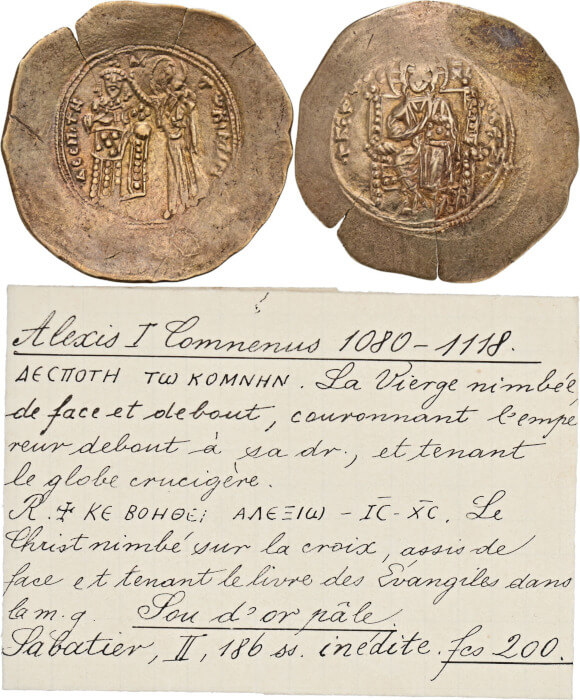

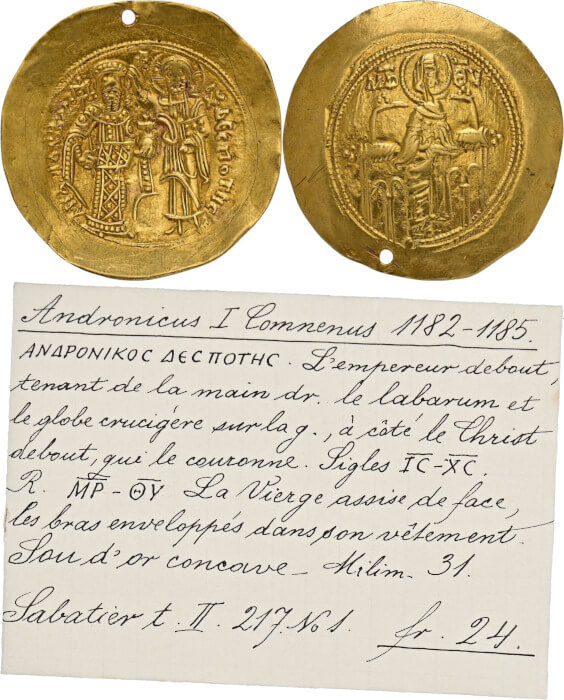

The collection comprises approximately 300 ancient coins, from the ancient Greek to the Byzantine era. As one might expect, the focus among the Greek coins is on the more well-known coin types, i.e. coins from the city of Athens or from the Macedonian rulers Philipp II and Alexander. The Celtic specimens are mostly imitations of the Thassian and Alexander coin types. Then there are numerous Roman coins, mainly denarii and bronze coins from the Republican and Imperial periods, and especially from the 3rd and 4th centuries. There are also some gold coins, mainly from the late Roman period. Clémentine furthermore specialized in Byzantine numismatics. She meticulously identified her coins using J. Sabatier’s catalog, Description Générale des Monnaies Byzantines, which was considered the standard reference even up until the 1970s.

The small slips of paper enclosed with her coins were probably from Clémentine’s own hand. A handwriting comparison with earlier letters – granted, a rather superficial one – suggests that she wrote the notes herself, albeit with a much higher degree of care and neatness than the letters.

Clémentine described the coins in accordance with standard practice of the time, including the complete legends on the obverse and reverse. She looked for a reference and gave a price in francs (the purchase price? an estimate? the insurance value?).

The references give us a hint as to when she was most involved with her collection. The publications mentioned on the slips of paper date to the end of the 19th century; it may therefore be that Clémentine only devoted herself to her coin collection toward the end of her life, which would also explain the careful script of an elderly woman. Incidentally, the auctions mentioned are probably rather to be understood as a reference than as a provenance.

The Princess apparently owned the work by Sabatier but not the most important catalog of Roman coinage at the time, which was written by Henry Cohen between 1859 and 1868 and was also available in a second edition from 1880. The Roman coins therefore appear to have been of less interest to Clémentine than the Byzantine coins. Otherwise, she most certainly would have acquired Henry Cohen’s work. She likely considered her interest in coins more as a historical diversion helping her to pass the long hours of her old age.

Please do not be surprised that Clémentine, despite her wealth, acquired coins that we no longer consider attractive today. As was common at the time, the collector did not see her coins as an investment, but as historical artefacts. As long as portrait and legend were clearly recognizable, a coin’s condition was not important. Even pierced coins and those with graffiti on them had a place in people’s collection since this gave collectors a sense of the myriad hands the pieces must have passed through.

And there is another modern viewing habit you will have to ignore for this collection: very much a child of her times, Clémentine took it for granted that the head or image of the ruler indicated the obverse of a coin. Whereas, today, we interpret the obverse and reverse technically – the obverse die is laid into the anvil, the reverse die is struck onto the coin – Clémentine describes her Byzantine coins in such a way that the obverse always features the image of the emperor.

It is a great stroke of luck that this collection has been preserved as an ensemble. We have therefore decided to keep it this way and offer it as a whole. After all, this collection is a superb example of a typical 19th-century coin collection. It deserves a detailed scholarly publication, as does the Princess’s activity as a collector. We would be thrilled if the collection attracts a buyer willing to undertake such a publication.

Bibliography

- Olivier Defrance, La Médicis des Cobourg: Clémentine d’Orléans (2007)