Maria Theresa and Her Persecution of Jews

On 23 June 2023, the Osnabrück auction house Künker offers a collection of Jewish medals in its auction sale 389, including some extremely rare pieces that bear testimony to the fact that the path to equal rights for Jewish citizens in Europe was an extremely arduous one.

Content

In this article, we present one of the most important pieces of the collection: a medal that refers to the last edict of the early modern period that deprived Jews of their homeland. It had to be repealed. In an enlightened Europe oriented towards economic success, the young, inexperienced and uncompromisingly anti-Semitic Maria Theresa was not able enforce her plans. Quite unlike her compatriot some 200 years later.

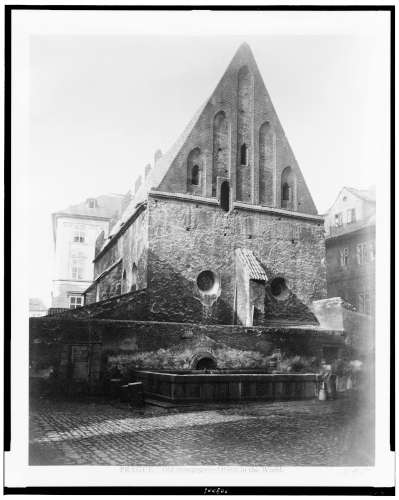

The Old New Synagogue in Prague, the oldest undestroyed synagogue in the world. Picture of 1860. Source: Library of Congress.

Josefov: Prague’s Jewish Ghetto

Today, the Jewish ghetto in Prague is one of the most visited sights in the Czech Republic. It is also known as Josefov (or Josefstadt in German) and was named after Joseph II. He issued the 1782 Edict of Tolerance, which brought freedom of trade to the Jews and put an end to the fragile autonomy within the Jewish ghetto. Joseph’s mother, on the other hand, had tried to solve Prague’s “Jewish question” in a completely different way.

The Expulsion

On 18 December 1744, Maria Theresa ordered all Jews to be removed from Prague by the end of January 1745, and from Bohemia by the end of June. It was a particularly severe winter when the more than 10,000 Jews of Prague’s ghetto had to set out to find a new home. This was a considerable loss for the capital of Bohemia: about one in four citizens had to leave.

The people flooded the surrounding villages, which obviously were not prepared for such a wave of refugees. Some unscrupulous peasants became rich by renting out stables and overcrowded houses to the desperate at exorbitant prices. Meanwhile, the Prague mob stormed the ghetto to get their hands on whatever the Jews had to leave behind.

State authorities and leading merchants reacted quite differently. They let the Empress know that her orders were completely unrealistic. In moving words, they described the misery of those who had to flee, their hunger, their fear, their helplessness. And they pointed out that the cramped conditions in refugee camps would naturally lead to the spread of epidemics, and those diseases would, of course, also infect non-Jews.

Even Maria Theresa herself came to realize that her orders could not be implemented as she had imagined. Shortly before the deadline of the second ultimatum, on 15 May 1745, she allowed the expellees to remain in Bohemia – but not in Prague – for the time being.

A Jew on a so-called Jews’ sow (Judensau) – an insulting allusion to the fact that Jews abstain from eating pork for spiritual reasons. This denigration can be found on the painted wood ceiling of a Prague town house and was created at about the same time as the Edict of Expulsion was adopted. Photo: UK.

Everyday Anti-Semitism

Although the educated opposed the edict on the Jews, Maria Theresa’s decision met with great approval within less intellectual circles. After all, it was wonderfully easy to brand Jews as scapegoats for the fact that first the Bavarians in the fall of 1741, then the Prussians in 1744 had been able to conquer Bohemia in the blink of an eye. If the Jews were to blame, the military did not have to listen to accusations of failure. If the Jews were to blame, Maria Theresa did not have to think about why she had not succeeded in enlisting the loyalty of Bohemian noblemen and peasants. If the Jews were to blame, no Prague craftsmen had to ask himself why his business was unsuccessful.

The expulsion of the Jews was a popular measure, and many simple-minded people believed it to be the silver bullet for a complex problem.

The Protest

Educated citizens saw this differently. Major Prague authorities opposed the order – not expressly but in spirit, and at great personal risk. They argued that, although the Jews were banned from living in Prague, this did not mean that they were forbidden to go about their business. Of course, they let Jews from surrounding villages pass the city gates during the day and did not check very carefully whether they had left the city before nightfall.

The highest authorities even passed laws forbidding the looting and seizure of Jewish property. In addition, officials regularly went to Vienna to persuade the monarch to revoke her edict.

Maria Theresia also received criticism from abroad. The first to intervene were the Netherlands. The powerful Jewish communities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam pushed through an intervention. The days in which Jews had been nothing but helpless victims were over and done with. They used their influence to support their co-religionists.

The same applied to the Jewish community of Hamburg, which convinced the Hamburg City Council to approach merchants in Vienna and make them aware of the economic consequences of the expulsion.

But also the Archchancellor of the Holy Roman Empire, the Mainz Archbishop, and his Cologne counterpart stood up for the Jews of Prague, stressing that an expulsion would result in an enormous damage to the Empire’s reputation.

The rulers of Great Britain, Denmark, Brunswick and Bavaria, even the Republic of Venice sent their ambassadors to protest. At first glance, Maria Theresa seemed completely immune to this.

She did not react until 1747, when the Bohemian estates stood up for their Jewish fellow inhabitants. In a letter to the Court Chancellery in Vienna, they provided her with a detailed breakdown of the economic damage that the expulsion of the Jews had already caused and would continue to cause in the future. They, the estates, wanted the Jews to return. And this is when the monarch finally acted.

She was reorganizing the tax system at the time and needed the approval of the estates. They agreed and one part of their deal was the revocation of the anti-Semitic edict. Of course, the state earned money from this: Maria Theresa received 300,000 gulden for it. Thus, in 1748, the Jews could return to their Prague ghetto, which had been completely destroyed, and had a guaranteed 10-years’ right to stay. In 1755, this period was extended.

Silver medal by Niklaas van Swinderen commemorating the repeal of the edict expelling Jews from Prague in 1748. From the Dr. Arthur Polak Collection. Extremely rare in silver, probably the only specimen on the market. Extremely fine. From Künker auction eLive Premium 389 (23 June 2023), No. 2674.

The Medal

These events are commemorated by a medal created by Dutch engraver and gold smith Niklaas van Swinderen. He worked in The Hague from 1736 to 1760 and left his mark with the letters N.V.S.F. (= Niklaas von Swinderen fecit) on the obverse.

The heading on the obverse reads EXILIO MINATO (= when exile was threatening). It depicts ruler Maria Theresa seated on her throne, the virtues of Justice and Charity to her sides. The fact that the depictions of Justitia and Caritas are not to be understood ironically is evidenced by the inscription in the exergue. Its translation reads: so that the Queen would not be suspicious of her servants in such affairs. Thus, the medal refers to the suspicion that the Jewish community of Prague had supported Habsburg’s enemies.

The given reference is 1st Book of Kings, 22:15. However, this does not help as depiction and inscription actually allude to 1 Samuel 22:15. The verse describes the murder of the priest Ahimelech. The text, whose content differs substantially from the actual inscription, reads: Let not the king accuse your servant or any of his father’s family, for your servant knows nothing at all about this whole affair.

In front of the Queen stands a commander. He points at a Jewish priest dressed in ritual robes, probably to make him the scapegoat for his own failure. The priest raises his hand in a gesture of oath, testifying to the innocence of all Jews. In his hand, he holds Urim and Thummim, the ancient oracle through which high priests could learn about the will of God. The chronogram must be rearranged and the many V (= 5) added to 10 each, to get the year 1744 – i.e., the year in which Maria Theresa adopted her anti-Semitic edict.

The fact that the medal does not refer to a biblical scene but to the expulsion of the Jews from Prague is not only demonstrated by the exact date of the announcement (18 December = 13 Tevet), but also by the view of the Lesser Town of Prague with the bridge gate, which was henceforth closed to the Jewish community.

The reverse has the motto DECRETO ABOLETO (= when the decree was revoked). Again, the exact day of the decree is given, namely 15 May or 13 Iyar. We get to look inside the undestroyed Temple of Solomon, whose two pillars Boaz and Jachin form the entrance. A lamb burns on the altar as a sacrifice, its shape is suspiciously reminiscent of the Order of the Golden Fleece, which had been revived by Maria Theresa’s father. The smoke of the offering rises to the heavens, indicating that the events were pleasing to God. In the temple courtyard, Jews thank God for their salvation.

The translation of the inscription, which is again somewhat different from the original quote, reads: These are the days that no one will ever relegate to oblivion, and which will be celebrated in all the provinces of the world throughout every generation. The quote refers to a verse from the Book of Esther (9:28), which celebrates the institution of Purim: These days should be remembered and observed in every generation by every family, and in every province and in every city. And these days of Purim should never fail to be celebrated by the Jews—nor should the memory of these days die out among their descendants.

In fact, Purim is still celebrated to day and commemorates the fact that Esther, the Jewish wife of the Persian king, convinced her husband not to execute the plan of his grand vizier, who had ordered that all Jews be murdered.

The coats of arms that can be seen on the left and the right evidence that the biblical story refers to real events. They represent the nations that supported the Jews of Prague, namely Great Britain, Denmark (not Sweden, as can be read in standard works), Poland and the Netherlands.

The chronogram in the exergue can be read as 3762. A date that has not been successfully interpreted so far. It stands for a Jewish year that corresponds to year 1 of the Christian era. Perhaps the artist was alluding to the fact that by revoking the Edict of Expulsion, a Christian ruler finally behaved according to Christian ideals.

About Two Centuries to the Holocaust

The expulsion of the Jews from Prague was the last major Jewish expulsion in Europe prior to the terrible events of the 20th century. Although this medal suggests otherwise, Maria Theresa did not revoke her edict because she understood that it had been wrong. She did so because she could not jeopardize the stability of her state even further. Until her death she claimed that there was “no greater plague” for her country than the Jews.

The widespread solidarity that the Jewish community of Prague experienced both from fellow belivers and throughout Christian Europe is truly remarkable. The ideas of the Enlightenment had firmly established the concept of the fundamental equality of all people, at least in some leading minds.

Secondary literature

- Stefan Plaggenborg, Maria Theresia und die böhmischen Juden. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur der böhmischen Länder 39 (1998), p. 1-16.

- Prof. Kinsky, Antwort auf die Anfrage im Hesperus VII. Heft 1816 S. 270, referring to a Jewish commemorative coin. In: Hesperus (1817), p. 142-143.