The Birth of the Krugerrand

by Ursula Kampmann

The South African Krugerrand is the world’s oldest bullion coin. When it was first minted in 1967, the concept of producing a coin that matched the weight of an investment unit –one ounce – was both new and innovative. Learn more about the economic background and the meaning of its design here.

Content

“Honor Lycurgus,” Pythagoras is said to have once proclaimed, “honor him, for he outlawed gold, the root of all crime.” Today, we tend to see things a little differently. Since currencies are no longer tied to gold, governments have started speculating with enormous amounts of money, pushing national debt into the realm of fantasy. Citizens fear inflation and seek refuge in gold. Fortunately, bullion coins offer an alternative to the traditional 12.44 kg gold bar, making investment more accessible for everyday people. And leading the way for these small-format gold pieces is the Krugerrand.

The Krugerrand Concept: A Circulating Gold Coin

On July 3, 1967, the first Krugerrands were struck at the South African Mint in Pretoria. Behind them lay a bold new idea: even though the Krugerrand had no face value, it was technically a legal tender coin in South Africa, its value determined daily according to the current gold price. To simplify things, it was minted with a fine weight of exactly one troy ounce (31.1034768 g).

The success of the Krugerrand quickly validated its concept. From modest beginnings with only tens of thousands minted between 1967 and 1969, production soared: 90,018 coins in 1970, 686,400 in 1971, and an impressive 869,300 in 1973.

Weak Currencies Drive People to Gold

The genius idea behind the Krugerrand was to distribute South African gold directly to small investors via banks and coin dealers, bypassing several links in the value chain. South Africa was the first nation to do this and would remain the leader for a long time. Not until 1979 did the Canadian Maple Leaf emerge as a serious competitor. No surprise, then, that the Krugerrand remains the most recognized bullion coin worldwide, despite today’s overwhelming range of gold investment coins.

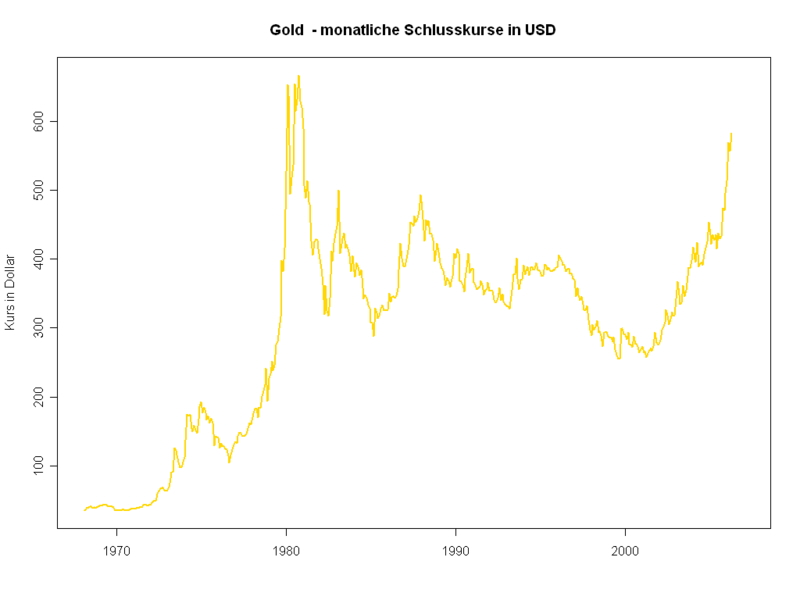

The Krugerrand benefited directly from global monetary policy, which, in the 1970s, drove countless thinking individuals to seek alternatives to the traditional savings account.

Let’s take a step back: Since World War II – more precisely, since the 1944 Bretton Woods conference – the US dollar had been the world’s reserve currency. In return, the US committed to backing its currency with a 25% gold reserve. Central banks outside the US, whose currencies were pegged to the dollar, had the assurance that they could exchange their dollars for gold at any time – at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

The 1970s: The Krugerrand’s Golden Decade

As is so often the case, government ambitions exceeded the means available. The United States began printing more money than its gold reserves could support. For a time, governments tried to manage the situation through new agreements. Member states were urged to redeem dollars for gold only as a last resort.

Since this made currency reserves useless, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) were introduced instead, controlled by the International Monetary Fund. Every five years, a central decision was to be made on how much additional money each country was allowed to print—without backing.

Gold was no longer the anchor of the global economy – and people quickly caught on. Ordinary citizens turned into investors, pouring their money into real estate or tangible assets when property was unaffordable.

The result? A massive boom in the coin trade – intensified even further in 1971 when the United States officially abandoned the gold standard. At that time, the gold reserves in Fort Knox were worth just around $10 billion – a laughable amount compared to the circulating currency. In fact, the five largest German corporations at the time could have bought up the entire U.S. gold supply with their liquid assets alone.

Gold from South Africa

The Krugerrand directly benefited from this global monetary instability. It was aimed at small investors who couldn’t afford large-scale investments. To meet demand, South Africa introduced fractional Krugerrands: the half-ounce (16.97 g), quarter-ounce (8.48 g), and tenth-ounce (3.39 g) coins.

Exports of the Krugerrand around the world gave a major boost to South Africa’s trade balance. At the time, South Africa was the world’s largest gold producer. In 1970 alone, it mined 1,000,439 kilograms of gold. For comparison: Australia produced 19,282 kg that year, the United States 54,225 kg, and the USSR 199,165 kg.

The Obverse Design: Oom Kruger

When the Krugerrand was introduced in 1967, John Vorster ruled the apartheid state with an iron fist. Under his predecessor, Verwoerd, the ANC’s internal opposition had been crushed; Nelson Mandela had already spent three years on Robben Island, and his political allies had fled the country. Unsurprisingly, the Krugerrand carried strong Boer symbolism, featuring national emblems of white South Africa on both obverse and reverse.

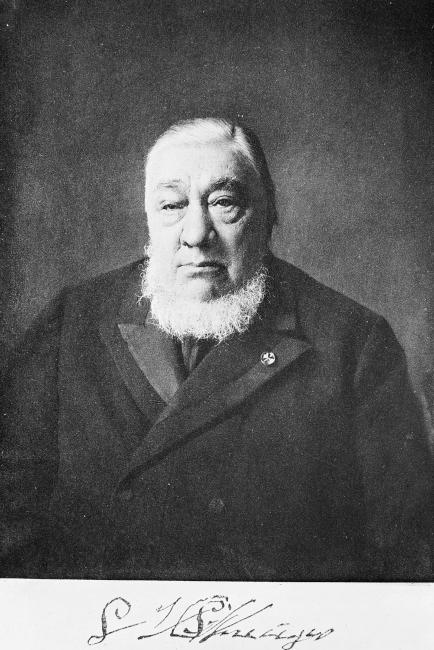

The obverse shows a left-facing bust of Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger – known as “Oom Paul” or “Ohm Kruger“ (Oom is Afrikaans for “uncle”). Kruger was a folk hero among the Boers.

Of German descent, Kruger was born in South Africa in 1825. His ancestor, born in Berlin, had come to the Cape in 1713 as a mercenary for the Dutch East India Company. At age 10, Kruger took part in the legendary “Great Trek,” when the Boers left the Cape Colony to settle further north. Throughout his life, Kruger saw himself as a deeply religious pioneer – part of a chosen people with a divine right to the land. He fought against indigenous groups such as the Ndebele and gained a reputation as a capable leader and organizer. In 1864, he was appointed commander-in-chief of the Boer forces in the Transvaal Republic. In this role, he repelled a British invasion in 1877 aimed at taking over the Transvaal diamond mines. By 1881, the British were forced to recognize Transvaal’s independence, and in 1883, Paul Kruger was elected the republic’s first president.

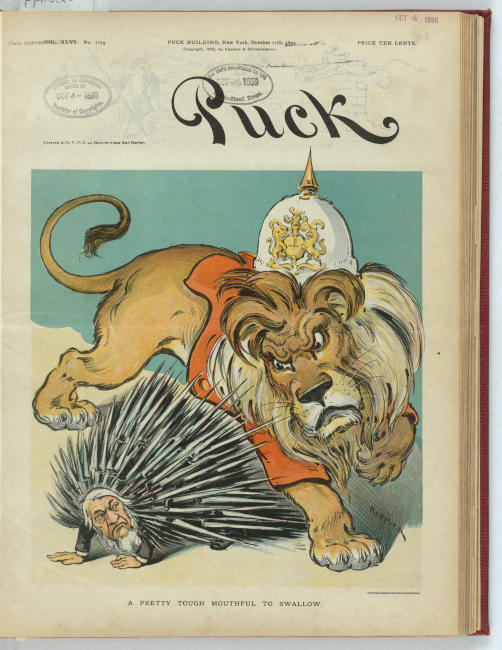

Caricature from the American magazine Puck, 1899. Porcupine Kruger proves not so easy for the British lion to swallow.

Kruger was still President of the Transvaal when gold was discovered in the Witwatersrand. Once again, the British – incited by Cecil Rhodes – tried to seize this wealth. However, their first small assault force in 1895, which had counted on the support of the “Uitlanders” working in Johannesburg, was repelled. Rhodes had to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1896 as a result.

But the gold finds were too significant, and England’s desire for them remained. This led to the Boer War in 1899. And England had vastly greater resources than the Boers. The war became a South African trauma. Both sides waged this conflict to the bitter end with great brutality, at the expense of the indigenous tribes. As an example: concentration camps were invented during the Boer War. Tens of thousands of women and children – and significantly more Black Africans than Boers – died from hunger and disease. Both British and Boers employed a scorched-earth policy, depriving tens of thousands of people of their livelihoods. After the war, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State had to be rebuilt from scratch.

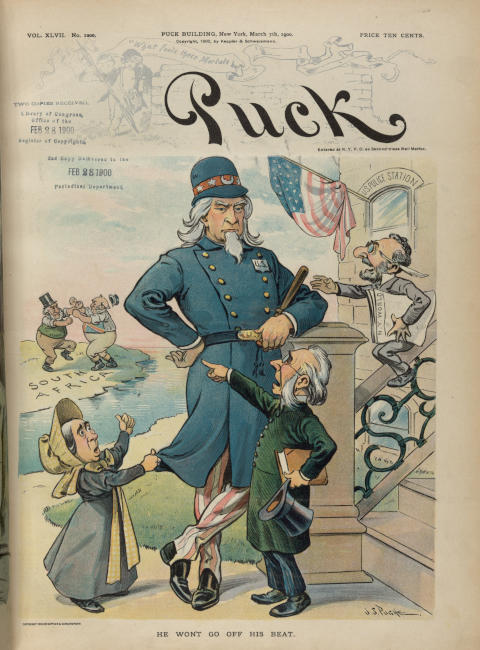

Caricature from Puck, 1900. Paul Kruger and his wife, together with the media, unsuccessfully try to persuade Uncle Sam to intervene.

Even though European sympathies lay with the Boers, no foreign power was willing to challenge the mighty British Empire over the Transvaal. Kruger, who traveled to Europe in 1900 in a final, desperate attempt to find allies, had to accept this reality. He resigned, remained in Europe, and died in exile in Clarens, Switzerland, in 1902.

Victorious England had lost so much face that it had to make concessions to the Boers in the peace treaty. Thus, Black South Africans were excluded from voting rights, while the Boers were granted full equality.

The morally strict Kruger was later romanticized as a tragic figure, a symbol of Boer resistance and of the suppression of Black South Africans. For many years, he was considered a founding father of South Africa, earning him his place on the obverse of the Krugerrand.

A male springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis). Photo by Yathin S. Krishnappa; edited by Wilfredor. cc-by 3.0

The Springbok

The reverse side of the Krugerrand features the springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), the national animal of the Republic of South Africa. It is not only depicted on the Krugerrand, but also on the circulating 1 and 2 Rand coins.

This magnificent animal inhabits the South African savannah and resembles the gazelle, though it belongs to a different genus and differs in the structure of its teeth. The name “springbok” derives from the vertical leaps it performs when startled. These jumps can reach heights of up to 3.5 meters. With speeds of up to 90 kilometers per hour, the springbok is one of the fastest animals in the world – only the cheetah is faster.

Boer-dominated South Africa adopted the springbok as a national symbol. The successful national rugby and cricket teams were both called the “Springboks.” Even the national airline, South African Airways, carried the springbok in its logo until 1997.

And Why Does the Krugerrand Still Look the Same Today?

The days of apartheid are long gone. South Africa has impressed the world with its commitment to reconciliation. A symbol of the hand Nelson Mandela extended to his former enemies is the Krugerrand, which still looks much the same as it did when it was first minted on July 3, 1967.

Nelson Mandela personally advocated for the retention of the springbok as a national symbol. The reason? The South African rugby team. In 1994, with the Rugby World Cup scheduled to be held in South Africa in 1995, the National Sports Council proposed renaming the now racially mixed team from the “Springboks” to the “Proteas,” after the national flower. Nelson Mandela opposed the change. He convinced proponents of the name switch that the team had the opportunity at the upcoming World Cup to redefine the burdened symbol in a new and unifying way.

And indeed, the team won the World Cup. President Mandela, wearing a Springbok jersey, personally handed the trophy to team captain Francois Pienaar amid thunderous applause. This day is now celebrated as a great moment of reconciliation, making the springbok not just a national emblem but a symbol of healing and unity.

That it’s also difficult to change the design of a globally recognized bullion coin in the international market… well, that’s a whole other story.

Caution! Some Krugerrands Are Collector’s Items

Do you have Krugerrands at home? Planning to sell them? Then be sure to check the minting year first. Because of boycotts against the apartheid regime, Krugerrand sales slumped in some years, and mintages were significantly reduced.

Rare mint years include: 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, and the rarest – 2000. While typically several hundred thousand Krugerrands were issued annually, the number of one-ounce coins minted in 2000 was exactly 6,657. Only 2,593half-ounce, 2,517quarter-ounce, and 19,567tenth-ounce coins were made that year.