The Suffering of Leiden – A Siege During the Dutch Revolt

by Ursula Kampmann

The third part of the Beuth Collection that Künker offers in Auction 420 contains many historically interesting emergency and siege coins. They were issued by the Dutch towns besieged by Spain during the 80 Years’ War. One of these towns was Leiden, which to this day commemorates the end of the siege every year with a festival.

On 7 October 1571, the Spanish and the Holy League won a glorious victory over the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Lepanto. Since Lepanto is quite far away from the Netherlands, one would assume that the battle did not impact this country, where a conflict between the Spanish government and a small number of municipal regimes had been smoldering since 1568. However, the outcome of the battle had a massive impact: the great victory over the Turks allowed the Spanish to withdraw soldiers from the Mediterranean and to deploy them against the rebellious Dutch. The Governor General of the Netherlands, the Duke of Alba – who became infamous thanks to Schiller’s works – was expecting reinforcements to arrive and ended all forms of polite diplomacy with those who had remained neutral in the conflict. He acted mercilessly, embittering all the cities that had been friendly to Spain before.

This is why William of Orange was met with a much more favourable atmosphere when he entered the Netherlands a second time in early 1572. Most of the towns in Holland and Zeeland sided with him, including the proud city of Leiden.

Leiden, Roman Lugdunum Batavorum, was one of the most important cities in Holland. It had become a confident trading city whose citizens were open to Protestantism and Calvinism. They enthusiastically supported William of Orange. But despite the cheers, the latter was forced to withdraw from the Netherlands in August already. What remained were the deceived cities that had over-hastily spoken out against Spain. They all paid a heavy price. With the help of the many soldiers available, the Spanish governor recaptured all the cities for his king. Mechelen and Zutphen suffered disastrous consequences: although they had surrendered by choice, they were looted and pillaged as if they had fallen to the Spanish after a long siege. The reason for this was that there was never enough Spanish money to provide soldiers with regular pay. Therefore, the Governor had no choice but to ensure the loyalty of his troops by allowing them to plunder.

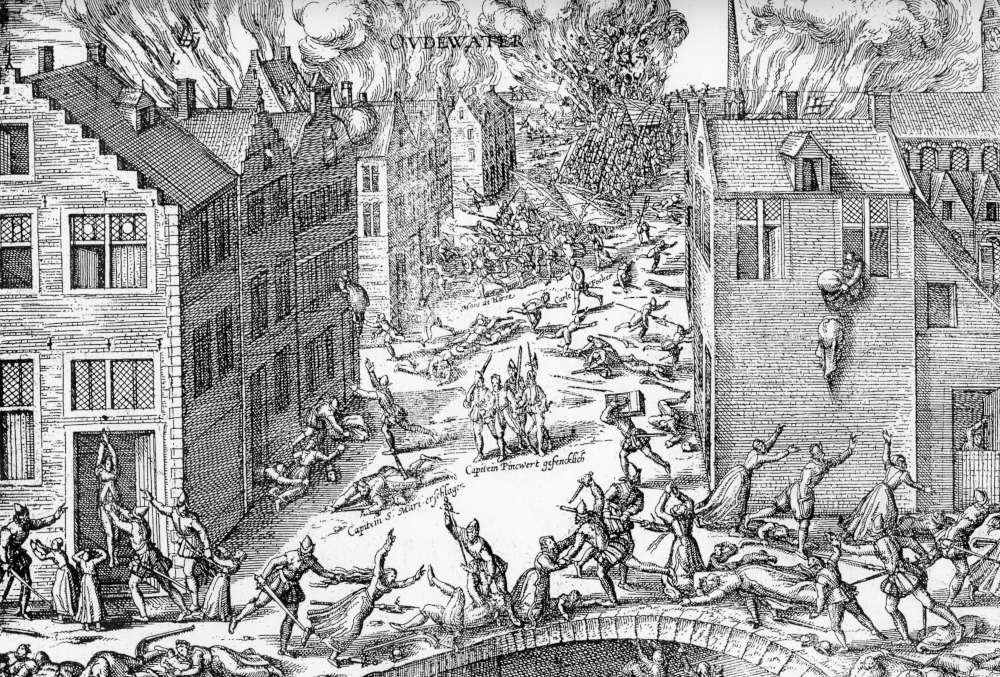

Dutch humanists had copper engravings produced that impressively illustrated the suffering that awaited a town after a conquest. These engravings were published throughout all Protestant regions. Here we see the sack of Oudenarde, conquered in 1582 after a long siege.

The fate of Mechelen and Zutphen prompted other cities allied with William not to surrender but to prepare for a siege. Haarlem became a shining example for all patriots. Although the city had to surrender eventually, its siege had cost so many Spanish lives that the city was henceforth known as the “Graveyard of the Spaniards”.

Leiden had all these stories in mind when it was surrounded by the Spanish troops on 21 August 1573. No supplies could get into the city, and no one could leave. Soon there was a terrible famine. In order to maintain control of the city, the city council of Leiden issued several edicts. Many of these were concerned with how to maintain an orderly economic life despite the adverse circumstances.

Leiden. Siege coin. 1/4 stuiver issued according to the edict of 12 November 1573. Very fine. Estimate: 100 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1431.

On 12 November 1573, the Hospital of St Catherine was authorized to mint copper coins worth 1/4 stuiver. On 19 and 24 December 1573, the council decided that more coins were needed. As there was not enough metal available, paper money was to be issued with a face value of 1 and 1/4 guilder. To make the job of counterfeiters more difficult, this paper was “struck” with coin dies. But even in a besieged city, paper money does not seem to have been very popular. Therefore, on 27 March 1574, the paper money was withdrawn and exchanged for copper coins.

Leiden. Siege coin. Cardboard guilder issued according to the edict of 19 December 1573. Very fine +. Estimate: 400 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1433.

Shortly afterwards, Leiden could breathe a sigh of relief. Louis of Nassau, the brother of William of Orange, had raised an army with French subsidies to free the besieged towns. The Spanish actually abandoned their siege and marched against the newly formed army. They destroyed the inexperienced mercenaries to the last man on 14 April 1574. Louis himself was killed in the battle. This brief interlude had given Leiden only a tiny break, and the city fathers had not even used the time to bring supplies into the city.

Leiden. Klippe of 28 stuivers issued according to the edict of 10 July 1574. Double taler. Extremely rare. About extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1437.

So things were back to square one, with Leiden being besieged by the Spanish. Nobody had taken the opportunity to quickly stockpile supplies. People suffered starvation, the plague was raging on, and the city fathers had to resort to church silver to issue new coins, one of which is the piece depicted here. The face value of the siege coin was 28 stuivers for a taler, and 14 stuivers for a half taler. Our example is a klippe, the blanks of which were easy to produce. On the obverse we see the city’s coat of arms in a cartouche. The inscription NOVLS – GIPAC is an abbreviation and stands for Nummus obsidionalis urbis Lugdunensis sub gubernatione illustrissimi principis Auraici. Translated, this means siege coin of the city of Leiden under the rule of the illustrious Prince of Orange. In addition, the specimen reads GODT BEHOEDE LEYDEN, invoking God to protect the city.

In fact, by the end of September, the situation was so desperate that the city fathers of Leiden decided on a last resort: they broke through the dikes and flooded the entire area. As a result, the ground could not be used for farming for years – however, the Spanish were unable to maintain their siege in the flooded area. They withdrew. On 3 October 1574, Leiden welcomed the Geuzen as liberators.

By this time, one third of the 18,000 inhabitants had died – mostly from starvation. William of Orange invested Leiden with the rank of a university city to honour their bravery. Thus, Leiden became the first Dutch university in 1575.

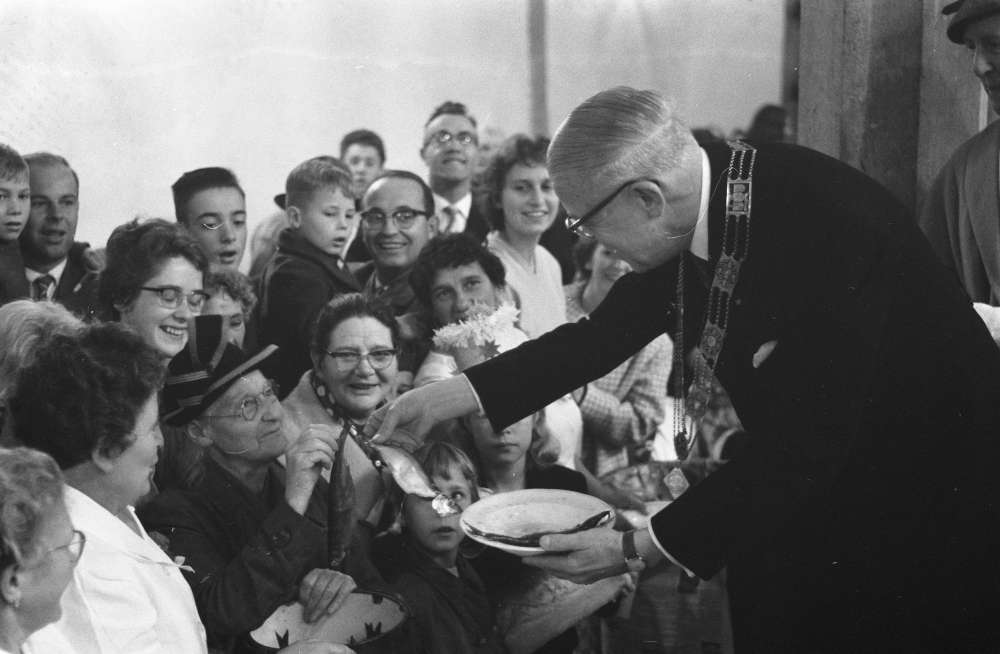

The distribution of herring in 1960. Nationaal Archief 911-6428. Fotograph Harry Pot / Anefo. cc-by 1.0.

To this day, the inhabitants of Leiden celebrate their liberation with great festivities on 3 October. Among the events of the celebration is the distribution of herring and white bread. Residents who come to the town hall at 7 am receive a bread and a herring. Few people today can imagine what it meant for the survivors of the siege to finally have bread and fish again.

Yet food still plays a central role in today’s festivities. On 2 October, people eat Hutspot together. This is a stew made from beef, carrots and onions. According to tradition, an orphan boy found a pot of this dish in the Spanish camp and brought it back to Leiden to prove that the Spanish had left for good. The pot is now in the museum and can still be seen there.