VOC: The Other Side of the Dutch Golden Age

by Ursula Kampmann

VOC coins from Künker’s upcoming Auction 420 tell the story of the Netherlands’ colonial past. The States General granted the VOC all the rights of an independent state: it could declare war, make treaties and issue its own currency. Join us on a trip to Indonesia, the place where the spices grew that financed the Dutch Golden Age.

Content

Dimly lit offices, the heady scent of cloves and nutmeg, respectable merchants dressed in black skirts with stiff ruffs: Is this the image that comes to mind when you think of the Dutch East India Company – the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie)? Or do you think of nutmeg plantations on the tropical Banda Islands, where sweating whites beat their Malay slaves for not harvesting fast enough? The VOC was both: a company whose organizational form still shapes our economy today, and an exploitative system that made a few men very rich and countless people very unhappy.

But let us start at the beginning: on 18 March 2025, Künker will auction off part 3 of the Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection with Dutch coins. This time, the sale includes issues of the VOC. They tell the story of how today’s economic world emerged and how money was detached from responsibility.

A spice market today: what used to be valuable treasures have become objects of everyday use. Photo: KW.

The Spice Trade as a Hope for Wealth

The story begins with a rather normal company, it just had an unusual destination. In 1594, a group of Dutch merchants founded the Companie van Verre (= Company for the Trade Beyond). It was normal for merchants to organize themselves in this way. No experienced merchant would invest in a single voyage. They spread the risk. If one ship did not return, another one brought a high return, which was shared proportionally among the investors.

The Companie van Verre, on the other hand, aimed to explore an unusual destination. After all, the Portuguese controlled the trade with the Moluccas. Pepper, cloves and nutmeg grew there. And these spices were much in demand throughout Europe – especially at court. The nobility were proud of their privilege to hunt big game and eat venison. We would probably have preferred to eat the grain porridge of the peasants. After all, the fridge had yet to be invented and the meat would go off quickly. Spices were the preferred means of masking its foul flavor. As a result, spices became incredibly expensive.

To make money from the spice trade, the merchants equipped four ships with 290,000 guilders. The ships returned in 1597 without having even reached the Moluccas. The leader of the expedition was truly incompetent. He brought home less than half of his crew and had bought only a few barrels of pepper. Still, those were enough to make a nice profit.

East Indiamen off a Coast. Painting by Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, between 1600 and 1630. Rijksmuseum / Amsterdam.

The Precursors of the VOC

Naturally, the whole of Amsterdam was talking about this expedition. And there was a consensus: with better leadership, the profits would have been even greater. Some well-read merchants quoted Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, who had published a detailed study on the spice trade the previous year. Huygen had travelled there on behalf of the Portuguese and claimed that the Portuguese system there was run-down. Their trading monopoly was protected by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which was guaranteed by the Pope. The Pope? The Dutch Calvinists were not interested in the Pope. After all, they had driven out the Spanish king. So, the merchants probably argued among themselves, why they should be intimidated by the Portuguese? A second expedition was equipped with haste, and it brought a return of impressive 400%. The result: by 1598, five different trade organizations sent their ships out; and 1601, 65(!) ships set off.

The Money for the Spice Islands

Until then, European merchants in the East Indies had used Spanish currency. The peso de a ocho had established itself as the most popular coin. The Vereenigte Amsterdamsche Companie therefore demanded to issue its own coins in the same weight standard. It was granted this privilege by an edict of the council issued on 1 March 1601. The Company of Middleburg was granted the same privilege in December of the same year.

The Lodewijk S. Beuth Collection contains the complete range of denominations minted by the Amsterdam company. The coins show the coat of arms of Holland on the obverse, and that of Amsterdam on the reverse. The lines and dots on the side of the coat of arms of Holland are remarkable. They allow even those who cannot read the Latin letters to see what the coin is worth.

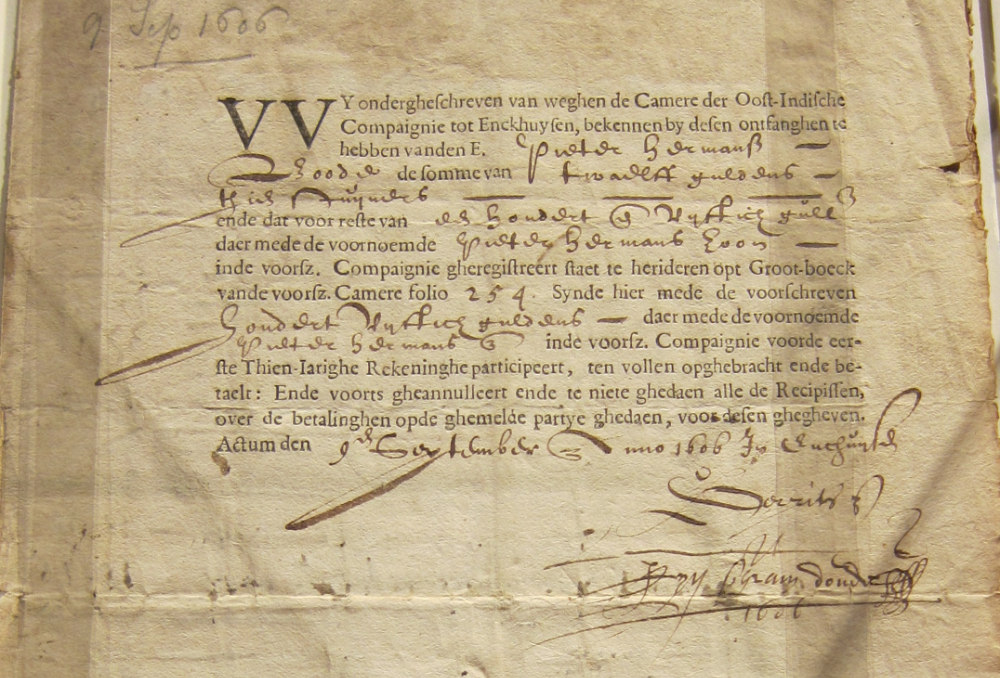

Share certificate of the VOC, issued on 9 September 1606 in Enkhuizen, purchased by Mayor assistant Pieter Harmensz. Westfries Archief, Hoorn, Oudarchief Enkhuizen. Inv. No. 424. Photo: KW.

Founding the VOC – a Matter of Supply and Demand

65 ships sailing to the Spice Islands, competing for spices there and bringing their goods to the market at roughly the same time – you do not need a degree in economics to understand what this means for the profit margin. It fell drastically. This gave rise to the idea of merging the various companies into one large corporation.

On 20 March 1602, the States General signed a privilege that gave a monopoly on East Indies trade to the newly formed Dutch East India Company (VOC) for 21 years. But this was not all. The VOC was also granted the right to sign treaties, declare war, establish colonies, raise an army, administer justice and mint coins.

In this way, the Dutch government outsourced the conquest, occupancy and exploitation of the Spice Islands to a privately funded company controlled by a board of directors at home. The so-called Lords Seventeen consisted of eight representatives from Amsterdam, four from Middelburg and one from Enkhuizen, Hoorn, Delft and Rotterdam. All involved cities, with the exception of Amsterdam, took turns in appointing the voting chair. This ensured that Amsterdam alone never would have an absolute majority.

Today, the VOC is known as the world’s first modern joint-stock company. Historians have pointed out that there were, of course, precursors. Think of the bonds of Italian cities that were traded like shares; or the so-called “kuxe”, mining shares that were used to finance the development of a new mine. And yet the VOC differed from previous financing models in two key aspects:

- Their financiers had no say in what the company did.

- The money was not invested in a single enterprise, but for a period of 10 years after which dividends were due. After that, shareholders could reinvest the money in the VOC – or refrain from doing so.

In theory, any Dutch person could invest in the VOC. In practice, this was only an option for very wealthy citizens, as each share was worth 3,000 guilders. In this way, 6.5 million guilders were raised by 1,800 investors.

The marketplace of Haarlem as a meeting place for merchants. The first stock exchanges were nothing but marketplaces with a roof, protecting merchants from the weather. Painting by Gerrit Adriansz Berckheyde around 1690/98. Kunstmuseum Basel. Photo: KW.

VOC shares immediately became a product whose price fluctuated daily. Even before shareholders had paid for their shares, the price had risen by 17%. The shares were bought and sold on the market. And since the affluent probably did not like to stand in the freezing cold – the Little Ice Age had Europe firmly in its grip at the time the VOC was founded – Amsterdam stockbrokers moved to the commodity exchange that the city had just built in 1612. As a result, the Amsterdam stock exchange is said to be the oldest one in the world.

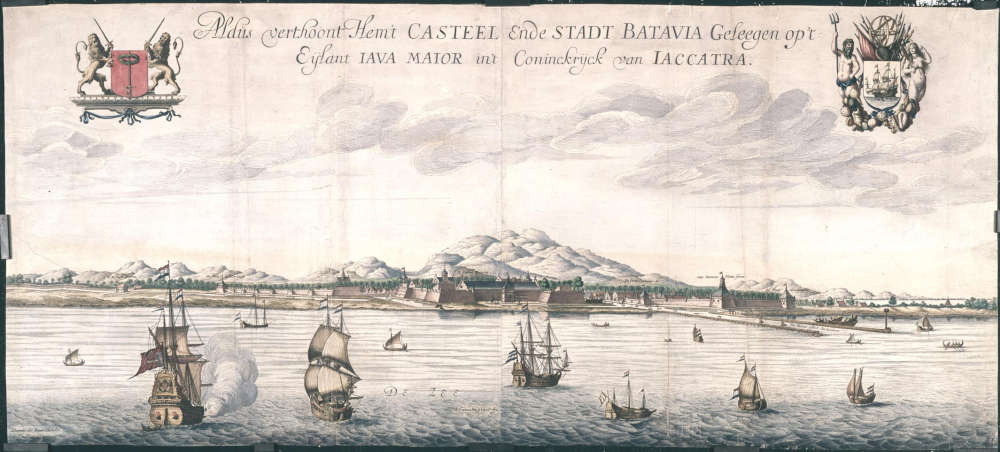

The Founding of Batavia

On 18 December 1603, the first fleet of the VOC set sail. Its mission was to seize the East Indies from the Portuguese, to make a rich booty and also to trade a little. The first conquest of the VOC dates back to 1605: the center of the clove trade on the island of Ambon. It was not to be the only coup. Nevertheless, the Lords Seventeen felt that things were moving too slowly: in 1610, they appointed Pieter Both as governor-general to improve local coordination.

Both had several forts built to ensure the VOC’s military presence. He recognized the strategic position of the city of Jayakarta on Java. However, the local sultan forbade the construction of a fort and allowed only a trading post to be set up. While Both had respected this, his successor, Jan Pieterzoon Coen, used brute force. He defeated the combined forces of the sultan and the English, burned down the town of Jayakarta and had Fort Batavia built, from which he controlled the whole of eastern Java.

To provide the necessary labor, he had 1,000 Chinese kidnapped from Macau. But only a few dozen survived the hardships of the voyage. Therefore, he ordered the survivors of the Banda massacre to settle in Batavia. There were 600 of them – after the conquest of the VOC, the 15,000 inhabitants of the Banda Islands had been reduced to 600 people.

By 1623, Coen could boast of having controlled the locals, and of having driven the Portuguese and the English out of the spice trade. The VOC now had a monopoly on all products from the Spice Islands. No one at home asked what Coen had done to achieve his.

Coins for the VOC’s Empire

Within a few years, the VOC’s trading empire stretched from the Red Sea to Japan. It was based on a dense network of fortified trading bases, where the goods to be traded were produced and collected. The VOC did not only operate as a long-distance trading agency. It engaged in any business that promised profit, ranging from glass making to textile production and beer brewing.

The VOC needed a well-working currency for its trading empire. Although it used the coins that were circulating on site, such as the Spanish peso or the Indian rupee, this was not enough. It was therefore decided to export coins minted at home. All of them feature the VOC’s monogram and often the coat of arms of the province of origin, as can be seen on these coins under the rider.

Batavia. 1/2 stuiver, 1644. Very rare. Beuth Collection. Very fine. Estimate: 100 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1604.

Nevertheless, cash shortages occurred time and again – particularly in Batavia. The administration made a first attempt to remedy the situation by granting a Chinese craftsman named Conjok the privilege of producing copper coins of 1/2 and 1/4 stuiver on 19 August 1644. Conjok produced these coins as he knew it from his homeland – by casting them. That is why the copper coins of the first issue from Batavia look different from the small change that was produced at the same time in Europe. On the obverse, the coins show the slightly altered coat of arms of Batavia: there is no laurel wreath on the upright sword. The reverse shows the face value and the monogram of the VOC.

The VOC seems to have been pleased with the coins. They commissioned Conjok again on 26 February 1645, together with a Dutchman called Jan Ferman. This time, silver coins with the same design and values of 48, 24 and 12 stuivers were produced. These pieces are so rare today that not even an obsessive collector like Lodewijk Beuth has managed to aquire one.

Batavia. 1 rupee, 1750, Batavia. Very rare. Beuth Collection. Very fine +. Estimate: 300 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1605

It was not until around a century later that the next decree on coinage was passed. On 17 February 1747, the order was given to mint what we now know as Java Rupee or Batavian Rupee. Contemporaries called them dirham or Javanese silver money. The coin weighing 20.5 stuivers was intended as an equivalent to the Indian rupee and bears Arabic lettering as a tribute to its target group. As the VOC’s seigniorage was too low, it decided to end the production of these coins on 18 June 1754.

Batavia. 1 rupee, 1766, Batavia. Beuth Collection. About extremely fine. Estimate: 200 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1607.

Production was resumed on 6 November 1764 and stopped on 15 January 1768, when enough coins had been minted to satisfy demand.

Batavia. Copper duit, 1764, Batavia. Very rare. Beuth Collection. Extremely fine. Estimate: 500 euros. From Künker auction 420 (18 March 2025), No. 1612.

The Duit

The most important fractional coin in the VOC’s trading empire was the duit. It was also minted in Batavia to push out foreign coins made of base metal. No surprise: the seigniorage for local small change was much higher than the profit made from precious metal coins. On 9 November 1764, the VOC declared the Dutch duit to be the only valid fractional coin of Batavia. All other forms of small change were confiscated without replacement.

The value was also fixed: four duits were equal to one stuiver; 120 duits were equal to one silver Java rupee; 264 duits were equal to one Spanish peso; 1,920 duits were equal to one gold Java rupee.

Another colony tells us what could be bought with one duit. A letter from the Cape of Good Hope tells us that the price for a pound of fat mutton there fluctuated between 20 duits in 1705 and 13 duits in 1714. Two Afrikaans idioms show that the duit has left a linguistic mark on South Africa: If you want to reprimand someone for speaking their mind without being asked, you say “ʼn Stuiwer in die armbeurs gooi” (=a stuiver in the poor box). And if something is not worth anything at all, you say it is not even worth “’n dooie duit” (= a dead duit).

Incidentally, the first settlers on the east coast of the US spoke of the New York penny when they meant a duit. This is linguistic evidence that the Dutch had founded New York.

The Demise of the VOC

In the late 17th century, the VOC was the most powerful trading company in the world. It owned around 40 warships and 150 merchant ships that transported goods from the East Indies to the Netherlands. Around 50,000 employees worked for the VOC worldwide, which is all the more impressive given that only about 2 million people lived in the Netherlands at the time. According to modern calculations, only one in three of the more than one million Europeans that the VOC sent to Asia returned. Only some of them survived the voyage to get there. Conditions on the VOC ships were not much better for employees than for slaves. And tropical diseases killed new arrivals like flies. The damage to the VOC’s reputation became so great that the Lords Seventeen ordered the confiscation of all the diaries of the returnees.

The misery in the East Indies made the Netherlands rich. The VOC poured so much money in Dutch cities that it was able to finance what we now call the Dutch Golden Age.

By the end of the 17th century, however, a fundamental problem began to emerge – and we are not referring to the VOC’s much-lamented corruption and inefficiency issues. The cost of enforcing the trade monopoly on the Spice Islands with its countless bays and anchorages was enormous. 10,000 soldiers had to be paid to maintain the monopoly. This cut into profits, especially when spice prices began to fall for a variety of reasons. Although the VOC continued to pay dividends, it had to take on more and more debt.

When the VOC declared bankruptcy in 1799, it left debts of 12 million guilders. They were taken over by the Dutch government and paid by taxpayers. In return, the Netherlands annexed the VOC’s colonial empire. Its provinces did not regain freedom until 1949. Today, the colonial past of the Netherlands is a difficult legacy to come to terms with that continues to be a source of debate.

Literature

- Stephen R. Bown, Merchant Kings. When Companies Ruled the World. Vancouver (2009)

- John Bucknill, The Coins of the Dutch East Indies an Introduction to the Study of the Series. Reprint New Delhi – Madras (2000)