Was Anarevito a Slave Trader?

by Chris Rudd

Until recently, the name Anarevito was completely unknown. It first appeared in 2010 on a coin likely issued by a king in Kent, England, shortly after the birth of Christ. Now the name has surfaced on another coin. Chris Rudd discusses this ruler, his coins, and his connection to the slave trade.

Content

A Remarkable Discovery

At 11:00am, Saturday, 4th March 2024, metal detectorist John White, 75, made a remarkable discovery near Dover. He unearthed a screamingly scarce gold stater of Anarevito who, two-thousand years ago, was probably king of east Kent. He may also have been one of the first British slave traders that we know by name. This superbly preserved gold stater – one of the prettiest I’ve seen – is important for five reasons:

Anarevito Horseman gold stater, struck in east Kent, c.AD 10-20. Only the second known. Found near Dover. PAS no: KENT-06535F. To be sold by Chris Rudd of Norwich, 17 November 2024. Picture: Chris Rudd.

- Until recently Anarevito was utterly unknown. No ancient author had mentioned him. No modern historian nor archaeologist had ever heard of him. No coins bearing his name had ever been found.

- It is only the second gold stater of Anarevito recorded. The first was found in 2010 and is now in the British Museum.

- This one is unique, struck from different dies, with a slightly different inscription. It confirms beyond all doubt that the ruler’s name was Anarevito, not Avarevito which, until now, had been a possible reading of the legend.

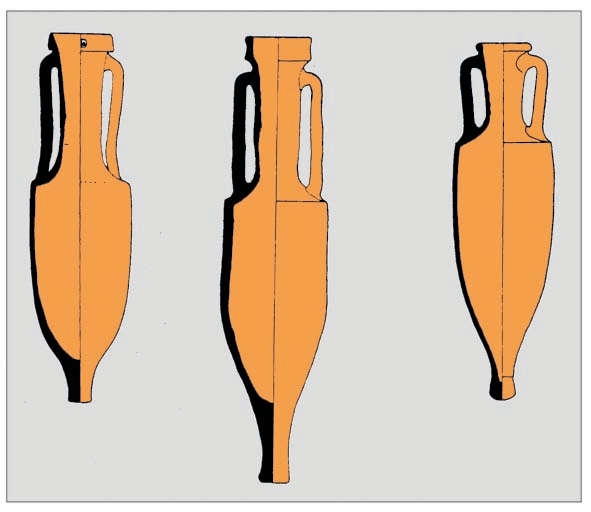

- This second gold stater of Anarevito was discovered only a mile or so from the first and only seven miles from Folkestone which in the Late Iron Age was the most convenient port in Britain for ferrying folk to France (ancient Gaul). Dover didn’t become a popular cross-Channel port until Roman times.

- This fact, plus the fact most of the other gold and silver coins attributed to Anarevito have also come from east Kent, leads me to believe that, of all ancient British rulers, Anarevito, possibly based at or near Folkestone, was perhaps geographically best placed to export slaves from Britain and to import wine from Gaul. The two gold staters, both found not far from Folkestone, also hint that Anarevito had the financial and political power to profit from slave trading. David Holman, who has extensive experience of Kent’s Iron Age coins and archaeology, agrees. He writes: “The evidence of Anarevito’s gold staters indicates that he would have held a sufficient level of power to have been a likely beneficiary of slaves.”[1]

Slave Trade

That Iron Age Britain exported slaves to Gaul and that slaves were traded for wine in Iron Age Gaul are both well attested by ancient and modern authors. Strabo (c.60 BC-AD 10) said that slaves were one of Britain’s main exports, along with hides and hunting dogs. [2] The skull of a large Iron Age dog was found at Folkestone (a hunting dog scheduled for export?). Diodorus Siculus (first century BC) specifically linked the Gauls’ love of Italian wine to the Gallic slave trade. He wrote: “In exchange for a jar of wine they receive a slave, getting a servant in return for the drink.” [3]

Plutarch, the Greek historian (c.AD 46-120), reports that Caesar was responsible for a million Gauls being captured and sold into slavery. This is celebrated on a silver denarius of Caesar which shows Gaulish captives with a trophy of captured arms. It is surely no accident that highly stylised images of this scene appear on three gold quarter staters (ABC 189, 192, 195) which were struck in Kent by Cantian kings who probably profited from selling captives to Romans in Gaul. Finds of these gold ‘trophy’ coins are concentrated in east Kent, including two from Folkestone.

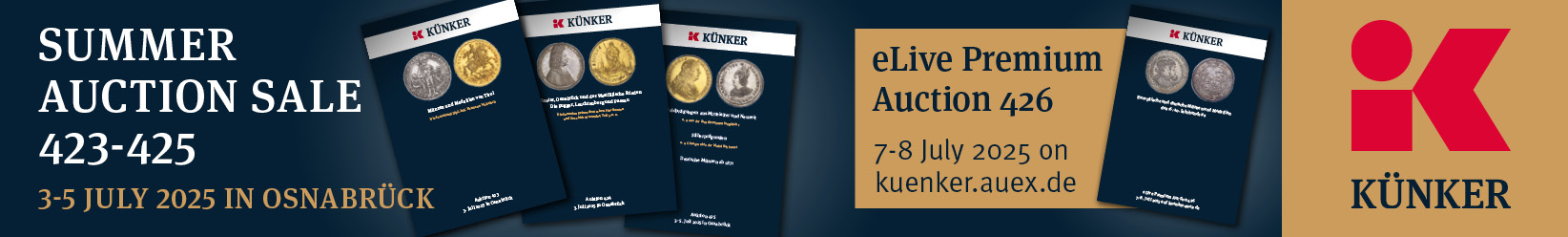

Types of imported wine amphorae found in Kent. Picture: D.P.S. Peacock & D.F. Williams, Amphorae and the Roman Economy, 1986.

Slaves in Exchange for Wine

Professor Sir Barry Cunliffe, Britain’s foremost authority on Iron Age Britain, writes: “Slaves were a valuable commodity in the Roman world and it is hardly surprising that British chieftains should capitalise on the fact… Slave-raiding, inspired by the profit motive, developed as trade with the Roman world increased following Caesar’s conquest of Gaul…Slaves become a cash crop practically overnight.”[4] The obsession that Britain’s Late Iron Age kings had with Italian wine is best illustrated by their coins. Many are wreathed in grapevines, adorned with vine leaves and bunches of grapes, and veritably clanking with silver wine cups, wine bowls and other vinous vessels. Importing fine Italian wine was evidently big business in pre-Roman Britain and, looking at the evidence of coins, it seems that Britain’s biggest pre-Roman rulers were deeply involved in this cross-Channel booze business, not just for profit, not just for prestige, but also for political advantage. In my view, Verica, high king of the Regini and Atrebates (c.AD 10-40) wins first prize for promoting himself as a wine merchant. Just look at his magnificent vine leaf gold staters, quarter staters and minims (ABC 1193, 1211, 1307). Verica makes it clear that his power as a wine importer is linked to his sea-power (see ABC 1259), as does Amminus, king of east Kent (see ABC 462). There is also compelling evidence from archaeology and numismatics that the Iron Age kings of Cantion (modern Kent), especially those in east Kent, exported slaves to Gallo-Roman traders in exchange for wine and that by the first half of the first century AD high kings north and south of the Thames had, or desperately desired, a controlling interest in Kent’s lucrative slaves-for-wine commerce.

- An Iron Age slave-chain was found at Bigbury Camp near Canterbury, only 12 miles from the pre-Roman cross-Channel port of Folkestone. Indeed, some archaeologists believe that Cantian hillforts such as Bigbury and Oldbury may have been used as holding stations for captives before they were taken to the coast via the North Downs trackway prior to deportation to Gallia Belgica in northern Gaul.

Two slaves (?) with amphora on coin from Kent, ABC 231. Similar ringed-bar on ABC 222. Picture: Chris Rudd.

- Many fragments of Gallo-Roman amphorae (two-handled wine jars) have been found in east Kent,including a piece from Bigbury Camp and some from Folkestone.

- A silver unit known as ‘Cantian Wine Carriers,’c.50-30 BC, ABC 231, found at Vagniacis (Springhead, coastal north Kent), shows two figures (slaves?) carryinga large, two-handled, Roman-style wine amphora between them. The two cabled bars with a ring at each end may represent slave chains and could perhaps be the first contemporary image of Britain’s Iron Age slave trade. A similar ringed bar can be seen on at least one other coin from Kent, ABC 222.

- A silver unit of Solidu, the last Celtic king of east Kent, c.AD 40-43 – he almost certainly ruled on behalf of Cunobelin, high king of the Catuvellauni, Trinovantes and Cantiaci – boldly features what to me looks like a slave chain on the obverse, with Neptune, the Roman sea-god, on the reverse (ABC 474).Significantly, Solidu’s Neptune was copied from a coin of the Roman emperor, Caligula, who was tempted to invade Britain in AD 40 (presumably intending to land in east Kent) and whose Neptune coin commemorates his grandfather, Agrippa, a well known Roman naval hero. So, in several respects, Solidu’s blatantly maritime and clearly pro-Roman coin reveals a strong connection between Cantion, cross-Channel slave trading and Rome.

- A similar ‘slave-chain’ coin, ABC 447, was struck by Sego ‘the strong’ or ‘victorious’ who seems to have ruled in east Kent for his father, Tasciovanos highking of the Catuvellauni. Having previously called Sego ‘king of the cross-Channel slave traders’, I’m still convinced he merits this title. He remains one of the most seriously underestimated warrior-kings of pre-Roman Britain; partly because time has been wasted wondering if the word sego and its abbreviations refer to a person, a place or a self-congratulatory epithet; and partly because Sego’s comparatively small gold coinage in Kent has led some numismatists to suppose tha the was short-lived and that his influence in Kent was also short-lived. In my opinion, neither supposition is correct. Sego’s brother, Cunobelin, wouldn’t have bothered to issue a special Cantian coin for him, paying Sego the very pointed, very public compliment of punning on his name, ‘victorious’, with a picture of Victory striding into Kent, flanked by the large letters S and E. Nor would Sego’s famous son, Amminus (almost certainly the historical Adminius cited by Suetonius), have wasted precious silver in flattering Sego with a name-check on two Cantian coins if Segohad died 10-15 years earlier without making a big name for himself in Kent, or was still alive in Kent,but toothless and powerless. Yes, I agree with Dr John Sills that Sego was probably the father of Amminus.[5]

Dr Daphne Nash Briggs thinks so too.[6] I believe that young Sego may have trained as a naval officer, possibly with the Roman fleet and that he quickly took control of his father’s cross-Channel commerce, which probably included trading British slaves for Roman wine. Sego coin finds are concentrated in coastal east Kent, with one of his staters coming from Dover and another from a small island off the coast of Denmark.

Were ships like this (ABC 2939) used for Kent’s cross-Channel slave trade? Picture: Jane Bottomley, 2009, © Chris Rudd.

- Even more significantly, a bronze unit of Cunobelin (ABC 2939), which everyone agrees was specially issued for use in Kent, features what I think may be a cross-Channel slave ship on one side, and SE (for Sego) on the other. Professor Sean McGrail,an expert on ancient boats, says: “If these Cunobelin ships had a waterline beam in proportion to their depth of hull, they would have been stable seaworthy ships of good cargo capacity [my emphasis], but not outstanding for speed. These characteristics, together with their weatherliness and their ability to operate from informal landing places, were necessary in cross-Channel trade [my emphasis].”[7] In other words, theses hips would have been ideal for ferrying a cargo of slaves from, say, Folkestone to Wissant (Caesar’s Portus Itius?), where Cantian flat linear potin coins have been found. The majority of provenanced Cunobelin/Sego ship coins come from coastal east Kent where unusually high quantities of Gaulish coins have been found.

Anarevito staters found not far from Folkestone, coastal hub of Kent’s slaves-for-wine trade (?) Picture: Chris Rudd.

Anarevito’s uncle was ‘vine leaf’ Verica, ‘king of wine merchants’. ABC 1193, 1211, 1307. Pictures a & b: F.W.Fairholt for John Evans, The Coins of the Ancient Britons, 1864, 1890. c: Chris Rudd.

Kent staters of Anarevito’s father have prominent grapevine wreaths. ABC 384, 387. Picture: F.W.Fairholt for John Evans, The Coins of the Ancient Britons, 1864, 1890.

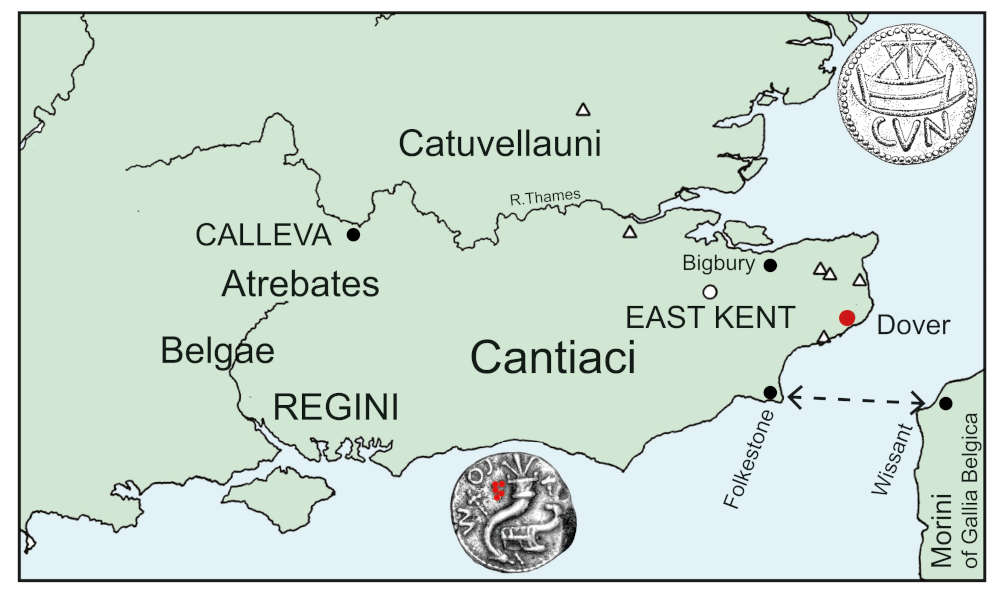

Iron Age settlement, Folkestone, with dog skull and Cunobelin Hunting Dog, ABC 2846. A safe port for Atrebatic slavers, Eppilllus and Anarevito, not near Catuvellaunian rivals in north and eastern most Kent. Pictures: Site photo David Holman, settlement reconstruction Smith Kriek Productions, drone image John Stevens, skull photo Canterbury Archaeological Trust, coin drawings F.W. Fairholt for John Evans, 1864.

Who Was Anarevito?

Like much of the above, what follows is very speculative. Anaverito seems to have been a privileged prince from one of the richest, most famous royal families in pre-Roman Britain – a privileged prince who, I fancy, may have taken advantage of his position, geographical as well as familial, to become a cross-Channel slave trader. Perhaps born at Calleva (Silchester) in the last decade of the first century BC, Anaverito was probably a son of King Eppillus, who was first king of the Atrebates of Hampshire, then king of the Cantiaci of Kent. He was probably a grandson of King Commios, founder of the great philo-Roman ‘southern kingdom’ south of the River Thames. He was also probably a nephew of King Verica, who was high king of the Regini and Atrebates. I suspect that Anaverito’s life was determined and dominated by the life (and death) of his presumed father, Eppillus, whose name means ‘little horse’ but who in reality was an eagle, a predatory regal eagle (see ABC 408, 411, 1160 and 1169) who swooped on his elder brother Tincomarus, and replaced him as rex at Calleva, probably prompted by Augustus. Then, after winning more wealth, more captives and more wine in Hampshire, this marauding warlord went to Kent, where he grabbed another even richer kingdom, again doubtless with the consent – even encouragement – of Augustus. I guess Eppillus took young Anarevito with him to help develop his new slaves-for-wine business in Kent. I also guess that the eagle and his eaglet nested high on the white cliffs of Folkestone, where they could see their shackled captives shipped off to Gaul and giant jars of Roman wine unloaded. A flight of fancy? Yes, but a substantial Iron Age settlement has been found at Folkestone – a clifftop settlement which would have overlooked the sea-eroded site of Folkestone’s Iron Age port. Anarevito was the last king in Kent to mint gold coins, but not the first to profit from people-trafficking. He apparently succeeded Eppillus in Kent, but I doubt that he was as successful as his father or that he lasted long. If Sego was the king of Cantian slave traders, Anarevito was at best a short-lived prince.

Acknowledgements

I’m most grateful to David Holman for all his expert advice and information.

Sources Cited

1.pers.comm. 14.7.2024.

2. Geographica 4.5.

3. Bibliothéké 5.26.

4. Iron Age Communities in Britain (1975 ed.) p.149, ibid (1991 ed.),p.524.

5. Divided Kingdoms: The Iron Age coinage of southern England,2017, p.785.

6. CR Auction 193, 17.3.2024, p.1.

7. Maritime Celts,Frisians and Saxons, ed. S.McGrail, 1990, p.43-44.