What is a Swede doing in Poland?

Ruthenia, Prussia, Mazovia, Samogitia and Livonia – this is what Sigismund is called in the inscription on this portugalöser of 10 ducats of 1612, which will be auctioned at Künker on June 26, 2019. King of Poland and Sweden? How did a Swedish prince become King of Poland? We recount the story.

Once upon a time there was a king who had three sons. This is the beginning of many fairy tales. In fact, Sigismund’s fate was less fairy-tale-like, but rather a juggling between the antipodes of the time: between Catholics and Protestants, and between nobility and kingship. But let us start from the beginning.

Similar to a fairy tale, Gustav I, the first of many Vasas to sit on the Swedish throne, had a vast number of ambitious sons, three of whom were to wear the Swedish crown one after the other. There was Gustav’s eldest son Erik, who was first to become king after him. There was Johann, only four years younger than Erik, who was made Duke of Finland by his father. There was Magnus, who later came to be excluded as heir to the throne because of so-called idiocy. And finally there was Karl, who was only 10 years old when his father died.

At first, Erik and Johann came to blows because Johann wanted to be more than the Duke of Finland, and was therefore looking for allies. He found them beyond the Baltic Sea, in Poland. If one considers the fact that the sea at that time represented a much better transport connection than any street, then Sigismund II Augustus, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, was the obvious choice.

Poland. Sigismund II Augustus. Ducat 1549, Vilnius, for Lithuania. From the Phoibos Collection. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2852.

On this ducat we see Sigismund II of Poland with a magnificent Renaissance portrait. The reverse shows the coats of arms of Poland, and Lithuania, including those of Kiev, Samogitia and Volhynia. The central shield of the coat of arms will look familiar to the connoisseurs of Italian coins. It presents the Biscione, the man-eating snake of the Sforza. After all, Sigismund’s mother Bona descended from this Italian family.

Sigismund had a beautiful and educated sister. Her name was Catherine and, as was the custom at the time, she became a pledge of trust between the allies Sigismund of Poland and Johann of Sweden – much to the annoyance of the royal brother-in-law Erik. He understood the extent of the power increase the alliance gave his brother. He accused him of high treason and locked him up in Gripsholm Castle for four years, together with his newlywed Catherine. In 1566, during captivity, the first son of the two was born. Programmatically, the parents called him Sigismund, like the brother and father of the Polish royal consort.

Poland. Gdansk. Medal by medalist Johann Höhn the Elder. Av. Circumcision. Rv. Baptism. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2919 – Medals like these were often given as baptismal gifts.

1566 – that was eleven years after the Peace of Augsburg, which had brought unstable and provisional peace to the Reich, without eliminating all conflicts. In the other countries there were still a lot of unresolved problems between the confessions as well. A wedding like the one between the Catholic Pole Catherine and the Protestant Swede Johann was possible, but now the fair – and quite political – question arose: How was their little son to be baptized? Catholic or Protestant? Of course, the baptism would also be a statement: Would baby Sigismund later orientate himself to Sweden or Poland?

The parents opted for a Catholic education. It was a safe bet for the prisoners. No Catholic prince would be able to dethrone a Protestant king in Sweden. In Poland, the situation was different: the country was an elective monarchy, and foreign princes had good prospects in every new election, as long as they were Catholic and brought enough money and soldiers.

We do not have to recount the entire history of Sweden here. Suffice to say that Erik’s decisions made him so unpopular with the nobility that they thought he was crazy. They decided to help Johann expel his brother in a bloody uprising, and to take over the crown in 1569.

He inherited not only the dominion, but also the struggle for hegemony over the profitable Baltic trade. The main competitor was Russia, while Sigismund II, brother of the Queen, remained the most reliable ally. Unfortunately, he died in 1572.

Poland. Stephan Bathory. ducat 1580, Olkusz. From the Phoibos Collection. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2854.

His successor Stephan Bathory was so vigorous and successful that he did not need the support of Sweden.

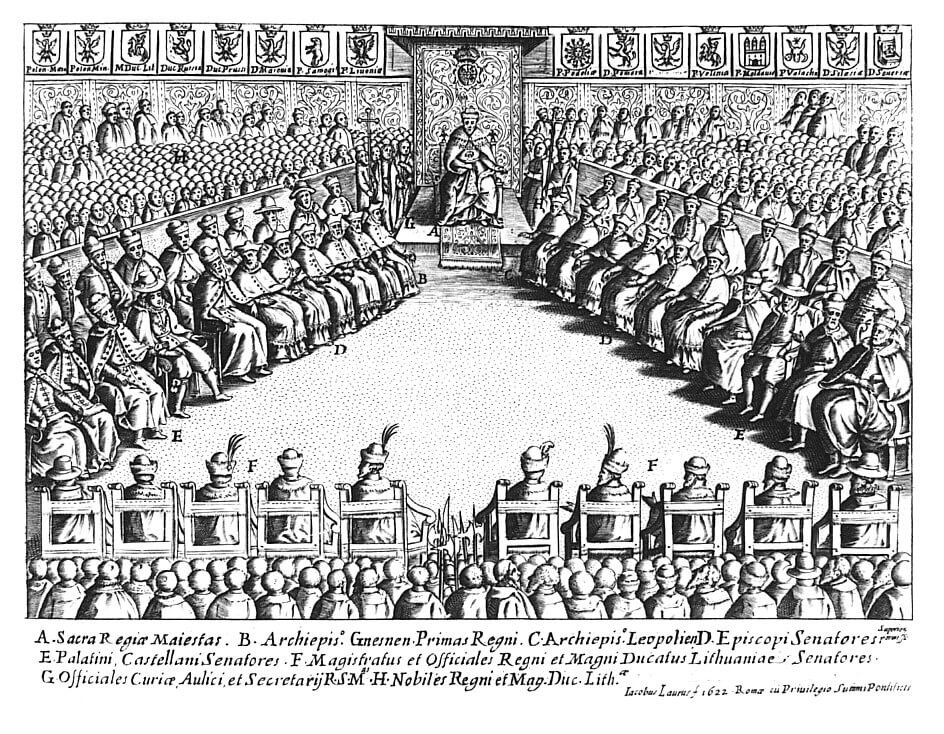

After Bathory’s death in 1586, Johann saw an opportunity for his now 20-year-old son: The Kingdom of Poland was an elective monarchy. As a Catholic and the grandson of Sigismund I of Poland, his son had great chances to be elected as the King of Poland by the Sejm. He succeeded. Unfortunately, he was not the only one. Maximilian III from Habsburg considered himself legally elected. However, Sigismund had a superior military, which enabled him to drive the Habsburg troops out of the country and arrest his rival.

Poland. Sigismund III 1/2 taler for presentation purposes struck in 1587 on the occasion of the coronation in Krakow. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2861.

After lengthy negotiations, Sigismund was crowned in Krakow on December 27, 1687. This coin is a reminder of this time. It depicts the Szczerbiec sword, the “jagged” sword, which is the only preserved part of the crown insignia of the Piast dynasty. It is named after a legend that links it to its first owner: it is believed to have received a nick when Boleslaw I struck the Golden Gate of Kyiv. Chronologically, this is not possible. Boleslaw died in 1025, while the Golden Gate was built in 1037. Either way, today you can visit the sword in the Wawel Castle in Krakow.

Incidentally, we know exactly how this sword was used in the coronation ceremony: The Archbishop of Gniezno picked it up from the altar before the actual coronation and handed it to the kneeling king. He recited a formula that asked the king to give justice to his people. A small reflection of this oath can be found in the inscription on the reverse: “For the Law and the People”.

Then the king handed the sword to the sword-bearer who sheathed it and returned it to the bishop. He girded the kneeling king. The king got up, pulled the sword out of its scabbard, swung it in the air three times in the shape of a sign of the cross, before putting it back in its scabbard. And of course, at each coronation, the entire nobility present whispered about how proficiently the king had handled the sword…

Poland. Sigismund III ducat 1609, Krakow. From the Phoibos Collection. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2858.

And so, a Swedish prince had ascended the Polish throne. Unfortunately, this prince was also the eldest son of the King of Sweden. As a result, he inherited the Swedish throne when Johann III died on November 17, 1692. Now, Sigismund was confronted with the problem of being Catholic.

Poland. Sigismund III reichstaler 1627, Bydgoszcz. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2859.

The youngest brother Karl played the religious card because it was his biggest asset. The Swedish nobility was firmly on the side of Sigismund. After all, a faraway king meant a lot of room for maneuver…

Karl, however, won over the common people. He is said to have gone to the markets even in the winter of 1596/7, in order to paint the horrors of a Catholic regime to the citizens and peasants. Thus at the Battle of Stangebro, it was not only Karl fighting against Sigismund, but also the nobility fighting against the people, and the tolerant fighting the fanatic Protestants. Fanaticism won. Karl became King of Sweden. Sigismund returned to Poland – of course without giving up his title and the coat of arms. Also on this taler from 1627, Sigismund is called King of Sweden and the Goths.

Poland. Wladyslaw IV 10 ducats ND (1636), Bydgoszcz. From Künker auction 323 (26 June 2019), no. 2862.

His son Wladyslaw IV Vasa, who in 1632 ascended the Polish throne, retained his title and coat of arms as well. We see the three crowns and read that he called himself the hereditary King of the Swedes, Goths and Vandals.

Sweden. Gustav II Adolf. Silver medal 1632 for the protestant victories under command of Gustav Adolf. From Künker auction 322 (24/25 June 2019), no. 1749

However, when this heir of Sigismund ascended the throne of Poland in 1632, the heir of Charles, a lion from the north, had already been devastating the German Reich for two years. His name was Gustav Adolf and he had become a fanatical Protestant. But that is a different story.

A detailed auction preview of Künker’s Summer Auctions is available on CoinsWeekly.

You can also find several videos on CoinsWeekly that show some of the most beautiful pieces of this auction.