Aquileia: A Centre of the Late Roman Empire

by Ursula Kampmann

Nowadays, Aquileia is a small town of a little over 3,000 inhabitants. Therefore, it does not really deserve its status as a city today. And yet Aquileia can look back on an impressive past, as it used to be a centre of world politics. In the 4th century AD, Aquileia was one of the capitals of the Roman Empire. It is where Maximianus Herculius spent much of his time. And it is where coins were minted that were used to pay the soldiers who fought off Germanic tribes on the Danube River. Depending on the estimate, up to 100,000 people used to live and work here.

Content

Located about halfway between Venice and Trieste, Aquileia is well worth a visit. However, you should not travel here in the summer when thousands of tourists with a keen appetite for culture invade the city from neighbouring Grado. While the quiet little town is visited by only one or two Italian school classes and a handful of tourists in the spring, in the summer Aquileia turns into an outpost of Venice’s Piazza San Marco – complete with a maximum number of people allowed in on weekends.

We were there just before Easter and enjoyed the peace and quiet. Not to mention the unobtrusive kindness of the guides, who made it their personal mission to show us every last piece of mosaic.

The ritual furrow around the colony is ploughed. Marble relief, 1st century BC, found in the southwest of the city. Today in the MAN, Aquileia. Photo: KW.

A Brief History of Aquileia

The area around Aquileia was originally inhabited by the Celts. This is what Livy tells us. They fell victim to the ambitions of the Roman consul Marcus Claudius Marcellus. He was looking for an alternative to war with the Macedonians, after the popular assembly had forbidden him to break the peace treaty with the Macedonian dynasty. Thus, Marcellus fought the Celts in Cisalpine Gaul instead, killing enough enemies to justify a triumphal procession.

This created a power vacuum in the Italian foothills of the Alps, and the Senate decided to fill it by having 3,000 veterans settle down in Aquileia.

With this colony, the Senate created a strategically located base that could be used time and again for military campaigns to the north and the east. After all, Aquileia was connected to several roads. For one, of course, there was Via Flaminia, which ran north from Rome via today’s Rimini and was extended to Noricum by Augustus’ Via Iulia Augusta. Moreover, Via Postumia ran through Aquileia, coming from Genoa via Cremona and the first bridge over the Adige to the east. But Aquileia did not only have excellent land routes. The city also had a river port, which connected the bustling commercial and artisan town to all the cities of the Mediterranean. And after the construction of a second canal, Aquileia became the most important port on the Adriatic.

Augustus acknowledged Aquileia’s importance by making it the main city of Regio X Venetia et Histria. Therefore, Aquileia was the centre of the civilian and military administration of Venetia and today’s Istria.

World history – at least in Roman terms – was first written in Aquileia when the city submitted to the Senate and closed its gate to Emperor Maximinus Thrax. The latter went on to besiege Aquileia and was murdered by his own troops in April 238.

Aquileia’s strategic position made the city a constant point of contention. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that Maximianus Herculius chose this city to set up his main residence. Understandably, this also included a mint.

The Mint of Aquileia

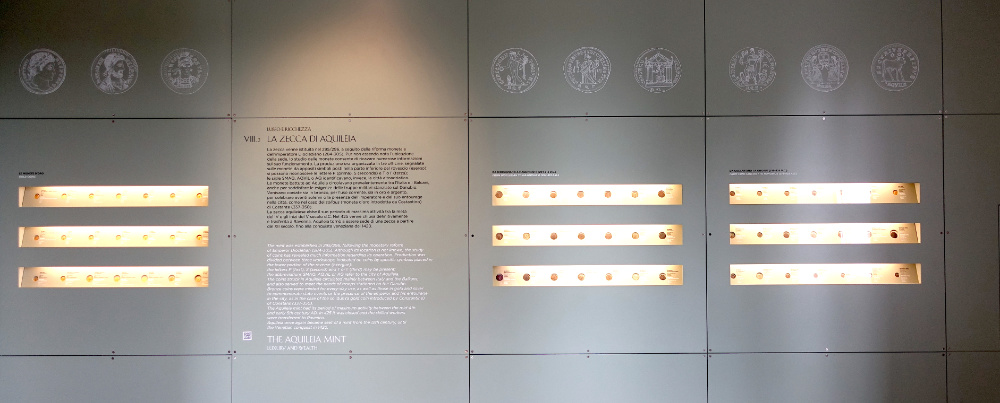

Although many traces of Roman civilisation have survived and can be visited in Aquileia, there are no archaeological remains of a mint to be found. The city’s numismatic legacy, on the other hand, is abundant and can be viewed in collections around the globe.

The mint was set up in 295/6, shortly after Diocletian reorganised the monetary system. From then on, it used the letters AQ as its mint mark. It mainly produced bronze coins, but also gold and silver issues if needed. Three workshops were in charge of the production of coins for Italy and the Balkans. Especially the troops on the Danube received their pay in the form of coins struck in Aquileia. In 324, the mint was closed for 10 years. When it was reopened, it was reduced to two workshops. The mint was permanently closed in 425 and the mint’s technicians were transferred to Ravenna.

The large and extremely interesting archaeological museum of Aquileia – MAN for Museo Archeologico Nazionale Aquileia – dedicated half a room to the city’s extensive coinage. The exhibition is well worth a visit. It systematically presents the Roman mint with a focus on issues from Aquileia and some coin hoards.

By the way, if you are interested in gems: the museum has an exquisite and excellently presented collection that is not to be missed – even though you have to climb up to the second floor to see it.

Aquileia: A Centre of Amber Carving

Unlike one might assume, the gems are not a collection but pieces that were found in Aquileia and the surrounding area. The fact that so many of them were discovered can be explained by the fact that Aquileia used to be a centre of Italian jewellery production – and this does not only concern gems. Aquileia was considered – as Pliny the Elder tells us in his Natural History – “the” centre of amber carving. It was here that the raw material, which had been brought to Italy from the Baltic coast, was transformed into works of art that were often used as burial objects.

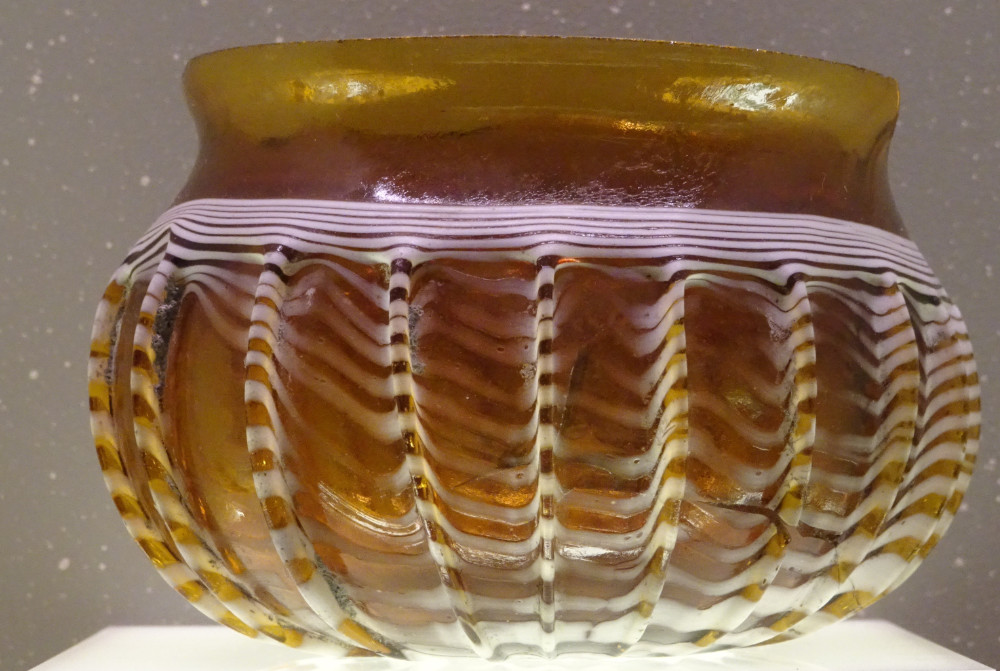

Aquileia’s Glass Production

Moreover, Aquileia was famous for its glass production. Even if historians now claim that neighbouring Murano acquired its glassmaking skills from the Middle East, another theory seems rather appealing to me. After all, the glassblowers of Aquileia were forced to leave their old home during the Migration Period and settled down in the Venetian lagoon. Perhaps some families preserved their glassblowing skills before the burgeoning economy of the High Middle Ages turned this luxury product once again into a speciality of Venice, which was distributed throughout the Mediterranean.

Noric Steel Worked in Aquileia

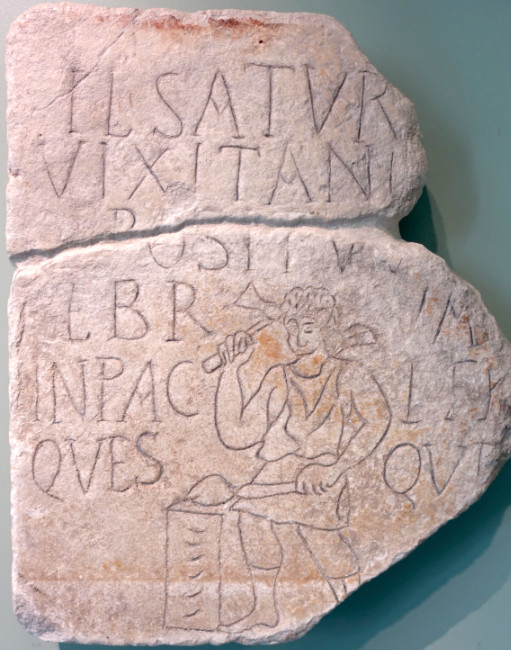

Aquileia was famous for yet another craft. In Aquileia, the Noric iron, which was highly appreciated by the Romans, was forged into the weapons the Roman army used against its enemies. The quality of the material was downright proverbial, as we know from Ovid. He compared the heart of noble Anaxarete to iron and steel refined in the fire of Noricum (Ovid, Metamorphoses XIC, 712).

View of the silted-up river port of Aquileia. You can still clearly see the steps that once led down to the water, and the embankments where ships used to be pulled ashore. In the background are the foundations of former warehouses. Photo: KW.

The River Port

All these objects were transported with ships. After all, the city had as many as two ports. Since Republican times, the marshland colony had been connected to the Adriatic Sea by the canalised Natissa River. In the late 3rd century AD, the city fathers built another canal. Thus, the city had a port in the east and one in the west, which made it the most important commercial port despite its position in the inland.

Luxury Goods from Egypt and Syria in Aquileia

This made Aquileia a major trade hub for luxury goods from the east, many of which can be admired in the archaeological museum today.

The Large Basilica

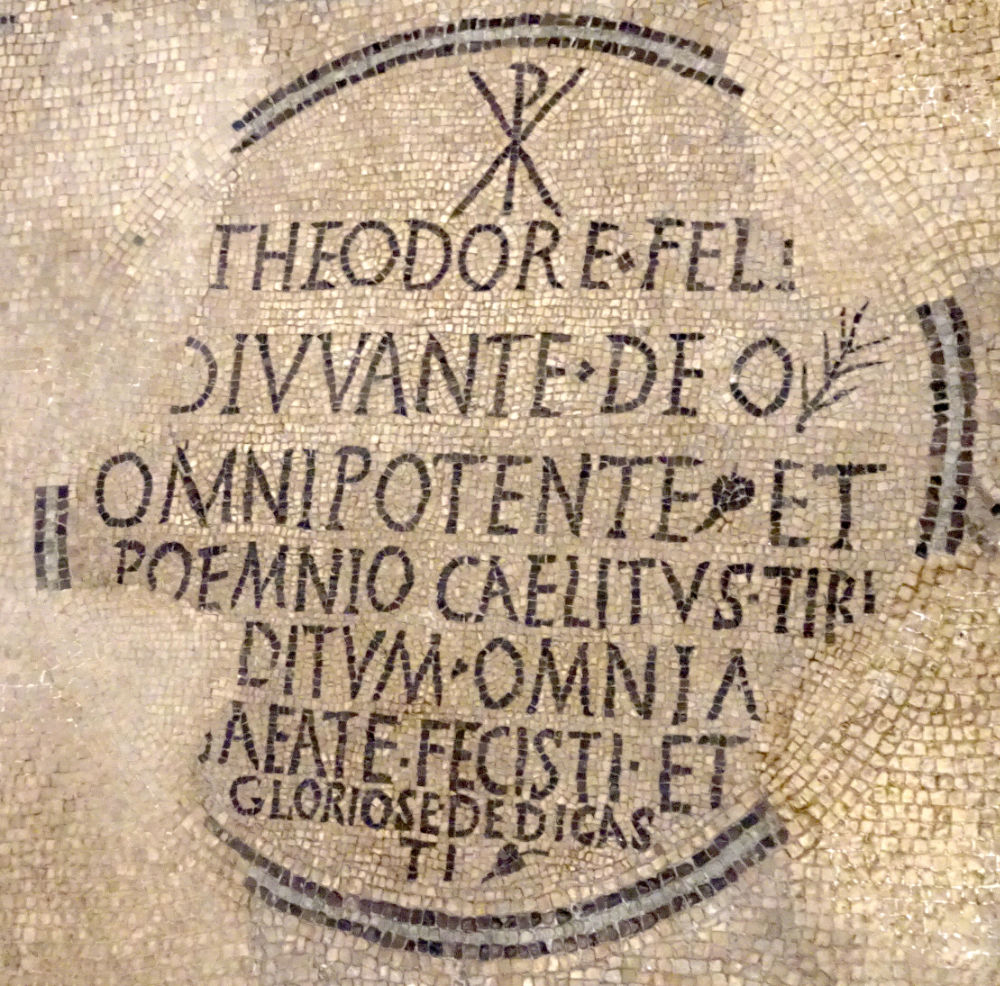

Let us face the truth: all those tourists do not travel to Aquileia to see the mint, the river port or the remarkable archaeological museum. They prefer another sight, the church of the Patriarch of Aquileia. What is special about it is that archaeological finds suggest that the construction began as soon as Galerius lifted all bans against Christians. Therefore, it can be proven that the basilica is one of the oldest churches in the world.

You probably remember that the Tetrarchs issued a sweeping edict against Christians in 303. Among other things, it included a ban on Christian worship and the destruction of all Christian churches. Galerius revoked the edict in 311.

Theodor, Patriarch of Aquileia, probably started immediately afterwards from 312 to 323 with the construction of a representative basilica, many of whose mosaics have been preserved to this day.

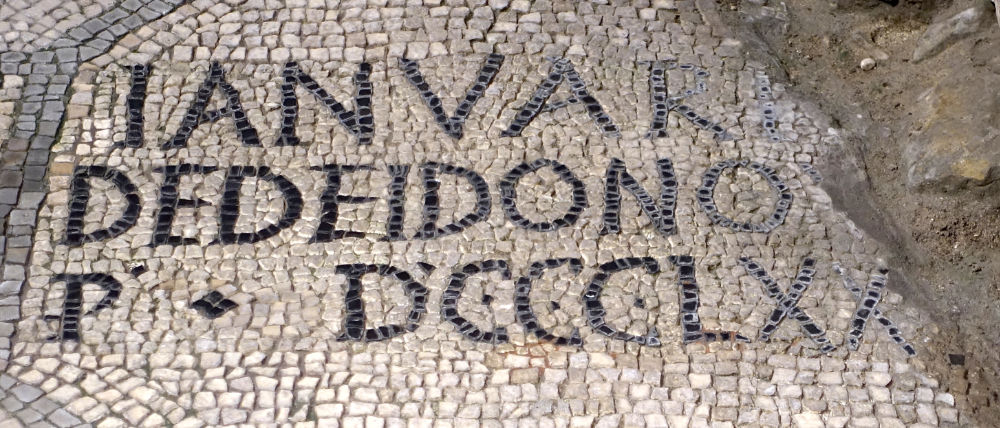

The translation of this inscription reads: Ianuarius promised 880 feet of mosaic as a gift to God. Photo: KW

The fact that those who funded the mosaics are named in the mosaic itself, together with the part of the work they paid for, is particularly fascinating.

It is a special experience for every visitor to see buildings with a history that dates back to the late Roman period still standing, because later generations preserved the Roman legacy and continued the construction – from the 5th-century baptistery to the Carolingian crypt, frescoed in the 12th century.

Berthold of Merania, Patriarch of Aquileia, 1218-1251. Pfennig, Slovenji Gradec mint. From Rauch auction 111 (2020), lot No. 203.

The church itself was built in the 11th century, following the model of the Church of St. Michael in Hildesheim, Germany. The Patriarch Poppo had a good connection to the German emperor, and was perhaps even related to Henry II. Anyway, after the latter died, even his successor Conrad II supported the Patriarch. Aquileia owes its minting privilege to this emperor, but only the succeeding patriarchs were to extensively make use of this right. The medieval Patriarchate of Aquileia reached the height of its power under Berthold of Merania, although the latter moved his official residence from Aquileia to Udine.

The Fortune of Decline

After that, not much happened in Aquileia. The world’s economic routes had shifted, and the marshland in the hinterland of the Grado lagoon was not a place where people wanted to spend time due to the illnesses that were widespread there.

This did not change until the 19th century, when tourists discovered Italian beaches. Aquileia belonged to Gorizia and thus to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. It even built a railway to Aquileia for its citizens, which is why sun-seeking tourists have been able to directly travel from Vienna to Aquileia since 1910 and then take the ferry to Grado. The ruins of the old patriarchal seat have become a major attraction and have been protected accordingly.

Aquileia has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998. The historical heritage is looked after by the Fondazione Aquileia, which coordinates the city’s attractions and makes them accessible to the public. Careful visitors may well need one and a half days to see everything. So allow for enough time if you get the opportunity to visit Aquileia.