Baldrs Horse: Detectorist Makes “Find of the Century” in Norway

By Anniken Celine Berger, Museum of Archaeology, University of Stavanger, translated by John Smestad Moore

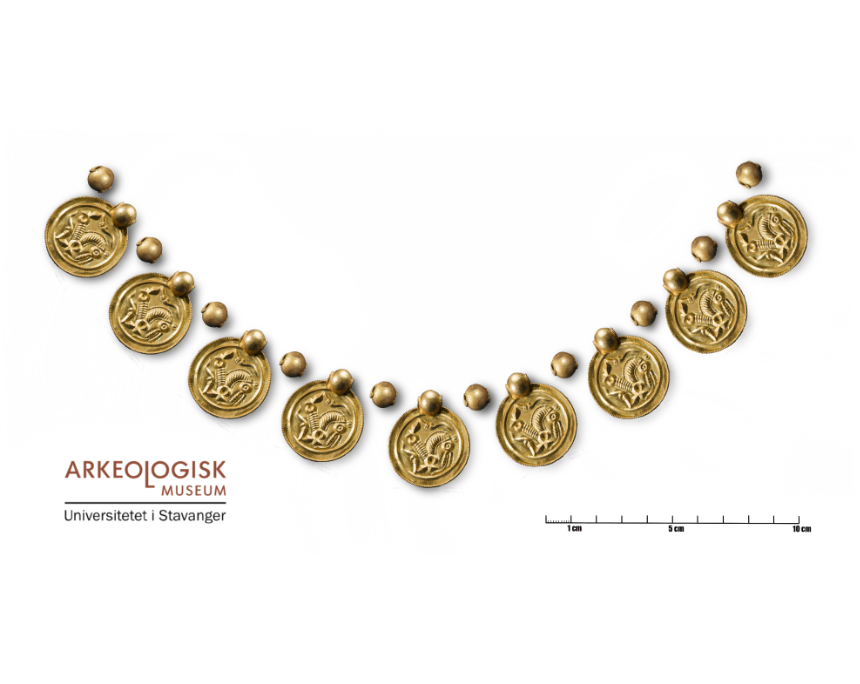

On the Norwegian island of Rennesøy, a metal detectorist recently discovered nine coin-like gold pendants engraved with rare horse symbols, along with ten gold beads and three gold rings.

Content

The find weighs just over 100 grams. “This is the find of the century in Norway. Discovering such a significant amount of gold at once is extremely rare,” said Ole Madsen, the Director of the Museum of Archaeology, University of Stavanger.

The Detectorist Thought He Found Chocolate Coins

Erlend Bore (51), a metal detectorist from Sola, just outside of Stavanger, made the discovery. He had purchased his first metal detector before the summer, partly to embark on treasure hunts but mostly to engage in a hobby that would get him off the sofa.

“I had been searching along the shore but only found scrap metal and a small coin. So, I decided to explore higher ground, and the metal detector immediately started beeping,” explained Bore. What he held in his hands was a clump of earth containing what looked to be gold coins. “At first, I thought I had found chocolate coins or plastic pirate treasure. It was surreal,” added Bore, mentioning how his heart raced when he realised the magnitude of his discovery.

The find was made on private property with the landowner’s permission. The Norwegian Cultural Heritage Act allows for finders of loose cultural artefacts to receive a finder’s fee, which is to be divided equally between the landowner and the finder. The determination of this finder’s fee will be made by the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage and has not yet been finalised.

First Such Find Since the 19th Century

According to Associate Professor Håkon Reiersen at the Museum of Archaeology, the gold pendants date from around AD 500, during the Migration Period in Norway. These gold pendants, known as “bracteates”, resemble gold coins but were used primarily as jewellery, not for buying or selling goods.

“The nine bracteates and the gold beads would have formed an exceptionally splendid necklace, which was crafted by skilled goldsmiths and worn by the most powerful individuals in society. Finding so many bracteates together is exceedingly rare. This is the first such find in Norway since the 1800s, and it’s also an uncommon find in a Scandinavian context,” stated Reiersen.

“Many of Scandinavia’s major bracteate finds were buried in the ground during the mid-500s, towards the end of the Migration Period. This period likely marked a crisis with crop failures, worsening climate and plagues. The numerous abandoned farms in Rogaland from this era suggest that the crisis hit this region particularly hard,” Reiersen explained.

“Based on the location of the discovery and findings from similar contexts, these were most likely either hidden valuables or offerings to the gods during that dramatic time,” Reiersen concluded.

Extremely Rare Horse Symbols

Professor Sigmund Oehrl at the Museum of Archaeology is an expert on bracteates and their symbols. So far, approximately 1,000 gold bracteates have been found in Scandinavia. According to him, the gold pendants from Rennesøy belong to a specific type that is extremely rare. They depict a horse motif in a previously unknown form.

“These motifs differ from those on most other gold pendants found so far. Typically, the symbols on the pendants depict the god Odin healing the sick horse of his son Balder. During the Migration Period, this myth was seen as a symbol of renewal and resurrection, believed to offer protection and good health to the wearer,” Oehrl explained.

However, the Rennesøy bracteates only depict the horse. A somewhat similar horse motif, along with serpent-like creatures, can also be found on a couple of gold bracteates discovered in Rogaland and South Norway.

“On these gold pendants, the horse’s tongue hangs out, and its slumped posture and twisted legs suggest that it is injured. Similar to the Christian symbol of the cross, which was spreading in the Roman Empire at the same time, the horse symbol represented illness and hardship, but also hope for healing and new life,” Oehrl noted.

Erlend Bore with the gold treasure and his metal detector. © Anniken Celine Berger, The Museum of Archaeology, University of Stavanger.

Shared Cultural Heritage

“This is an entirely unique find. None of the archaeologists in Rogaland County Municipality have ever experienced anything like this, and it’s difficult to describe the excitement we felt when we saw these,” said Marianne Enoksen, Head of the Cultural Heritage Department in Rogaland County Municipality.

All objects dating before 1537 and coins older than 1650 are considered state property and must be reported. The county municipality serves as the primary point of contact for archaeological finds made by private individuals. The finds are registered by the county municipality before being handed over to the Museum of Archaeology.

“We commend the detectorist for doing everything right when he made this exceptional discovery. He marked the find location and stopped searching immediately. He contacted us, and we informed the Museum of Archaeology. This allowed us to return to the discovery site shortly after to conduct further investigations,” Enoksen concluded.

This video lets you see more of the find and it’s location.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.