Lars Emil Bruun (1852–1923): From the Local Inn to an International Enterprise

by Ursula Kampmann on behalf of Stack’s Bowers Galleries

The auction of the exceptional Bruun collection, 100 years after the collector’s death, has attracted a great deal of attention. But who was Bruun as a person? What inspired him? On behalf of Stack’s, Ursula Kampmann went in search of Bruun’s personality and compiled a short biography.

Content

Every collection is unique – and so is every collector. If you want to truly understand a collection, you need to know the person who assembled it. This is difficult enough when it comes to collectors who are still alive. With people like Lars Emil Bruun, who passed away 100 years ago, it is almost impossible. While it is easy to gather the most important facts and figures, it is a real puzzle to try to understand their personality. All the little pieces of information must be put together in the right way to paint an accurate picture. Each new piece has to be placed carefully and can sometimes change the picture in a surprising way. In this article, we will try to put together what we know about Lars Emil Bruun. It is only possible for us to do this because Lars Emil Bruun’s grandson, Ioann Bruun, and the regional historian Flemming Weye published a monograph called Smør og mønter (Butter and Coins) in 2006, presenting a comprehensive study of the archival sources on the subject. Their work forms the basis of the following article.

A Dynasty of Rural Innkeepers

Lars Emil Bruun was born on 29 March 1852 in the small Danish village of Havdrup Ulvemose.His cradle stood in a mill that his father Ole Bruun had leased. Lars Emil’s father must have had an adventurous spirit. Although he could have comfortably continued the successful business of his ancestors, he chose to become a sailor at a young age. The Bruun family – the Danish equivalent of the English “Brown” – had run the thriving local tavern in Ordrup, a small village about 11 kilometers north of Copenhagen, since 1768. Their establishment was a kind of inn where guests could stay the night. It was also a place where farmers could buy and sell their goods. The Bruuns also owned large tracts of land, which Ole’s enterprising grandmother had acquired.

Ole did not want to help his father with the local inn. Instead, he obtained his boatmaster’s license and did not return to Ordrup until after his father’s death on 4 April 1844. It is unclear why he did not stay in Ordrup once he had returned. Instead, he leased the mill of Havdrup Ulvemose in a completely different corner of Denmark as early as November 1850. Perhaps he did not get along with the people in Ordrup. Or perhaps the inn did not make enough profit under his management – after all, Ole Bruun did not seem to have much of an entrepreneurial spirit. He also stopped running the mill at Havdrup Ulvemose in 1857, even though he had been granted a concession to operate the mill.

He returned to Ordrup, where in the late 1850s there was increasing economic opportunity. A railroad line connecting Ordrup directly to Copenhagen was completed in 1863, allowing both goods and people to be transported quickly to the capital, in turn stimulating growth. This period from 1800 is now considered the golden age of Denmark, a time when everything seemed possible. But one year later it all came to an end: the 1864 Second Schleswig War (also known as the Prusso-Danish War) shattered Denmark’s dreams of becoming a superpower.

The conflict was over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig, which were claimed by both Denmark and the German Confederation. As the war wore on, it became clear that the Danish troops were no match for the combined Prussian and Austrian armies. Little Lars Emil was 12 years old at the time and, of course, far too young to fight. But he was old enough to make friends with the many Danish soldiers who stayed at his father’s inn. He eagerly studied the newspapers, which published long lists of war casualties. He followed the fate of his new comrades closely and became an ardent patriot in the process. For him, Schleswig and Holstein always remained Danish.

Ole Bruun in August 1886 with his four daughters Sophie, Johanne, Annette and Emilie. The girl on the far right is probably his foster daughter Godtfrede Hemmert. Photo: Stack’s Bowers Galleries.

Hard Years in Holbæk

In 1866, the Danish government had to accept that Schleswig and Holstein were lost. This not only cost the country 40% of its population but also meant losing a number of important ports, the second university in the country, numerous industrial enterprises, and – particularly painful – the most agriculturally productive provinces. Lars Emil Bruun, who corresponded in many languages, never could bring himself to write in German, and this traumatic loss may be the reason why.

Denmark was to recover economically quickly. Astute politicians pushed for reforms to “gain from within what was lost outside.” During this renewal, the Danish education system was also modernized. However, these reforms came too late for Lars Emil Bruun. He received his patchy education partly in a public school, partly in private schools, and through home schooling with the local pastor. On August 1, 1866, his father put him into an apprenticeship, as was customary in the bourgeois circles of Europe since the late Middle Ages.

Thus, the 14-year-old learned the trade of a merchant in the business of C. E. Nissen in Holbæk. This meant working hours from 6:00 AM to 10:00 PM in summer and from 7:00 AM to 9:00 PM in winter. Sunday? Theoretically, the shop was closed during mass, but the back door remained open because the farmers had time to do their business on Sundays. The work was hard and physically demanding. Young Lars Emil particularly hated “laying herrings,” which meant transferring pickled salted herrings from the merchant’s large barrel to the smaller containers of the farmers. He later vividly described how the salt particularly affected his frostbitten hands in winter. During these four years, Lars Emil saw his parents only twice. Traveling the approximately 65 kilometers to Ordrup was time-consuming and costly.

No apprentice had extra money back then. He received only food, clothing, and lodging for his hard work. He shared a tiny room with a journeyman, where rain dripped through the ceiling. The bed was too narrow, rags served as covers, but that was not the worst part. Bruun later recounted with horror that the housewife always bought too much meat, which then spoiled. Of course, it wasn’t thrown away but served to the apprentices, who were relieved if they didn’t have to eat it under the housewife’s watchful eye. That gave them the chance to get rid of it.

Essentially, there was only one thing that comforted Lars Emil back then: the coins with which he could splendidly dream away into past times and other worlds. In these tough years, Bruun’s love for numismatics developed. It not only provided him with relaxation but also the friendship of an artist who was also interested in coins, whose wife gladly mothered the apprentice. The young collector acquired 49 silver and 87 copper coins during that time. Even much later, he would be proud of them.

First Steps in the Business World

The apprenticeship ended on September 25, 1870. From that date, young Bruun received an annual salary of 200 Rigsdaler, plus room and board. Bruun stayed with Nissen for another year and a half before leaving with an excellent reference.

Instead of immediately seeking a new employer, the barely 20-year-old decided to make up for his lack of theoretical education. He enrolled as a student at Grüner’s Commercial Academy. Its founder, Haldur Grüner, was then considered the leading Danish economist. The sons of major merchants also studied at his Copenhagen institute. Lars Emil, though far superior in practical experience, had a rather poor basic school education. He had much to catch up on before graduating with one of the best exams of his year.

This earned him an excellently paid position for his age with the wholesaler P. F. Esbensen. He now received 1,000 Rigsdaler annually, though without room and board. This position was crucial for Bruun. Here, he learned everything he would need to know later about the butter trade. His enterprising boss was among the first to turn to this highly lucrative commodity. Esbensen bought butter on a large scale; although Lars Emil Bruun didn’t actually like butter, it was his job to sample butter from hundreds of barrels to ensure the quality of the merchandise. Esbensen packed the butter in small tin cans to ship it as a luxury item, especially to the warm countries of the world where butter was hardly used until then. Bruun fondly remembered this time, although the working hours now seem unimaginable: from 7:30 AM to 12:00 PM, from 12:30 PM to 4:00 PM, from 5:00 PM to 8:30 PM, and from 9:00 PM to 10:30 PM, a total of 13 hours. On Thursdays, they worked far past midnight because the load had to be ready for the steamships that left for England every Friday morning. England was one of the most important markets for Danish butter, which led the coin collector Bruun to develop an interest in English coins.

P. F. Esbensen was becoming one of the largest butter traders in Denmark when Lars Emil’s father, Ole, reappeared to demand that his son drop everything to help him out of an economic crisis.

The Loss of the Family Fortune

One day, Lars Emil Bruun must have imagined throughout all those years, he would start his own company with his share of the family inheritance. But what he found in Ordrup at the beginning of 1877 was an economic disaster. The family fortune had been squandered, and there were substantial debts on all the properties. Father Ole had tried to upgrade the family’s real estate through infrastructural improvements to sell it at a high price. When he got into financial trouble due to the economic impact of the Long Depression, which was also felt in Denmark, he turned to one of the worst usurers in Copenhagen. He could no longer manage the annual interest burden of 28-48%. Lars Emil Bruun was left to manage his father’s bankruptcy in an orderly manner and to ensure that the name Bruun retained its good reputation in business circles. He personally took responsibility for all debts that could no longer be covered by the family fortune, even though it would take many years.

In 1877, Lars Emil Bruun was at his lowest point. He had lost his job and any hope of an inheritance. His mother had 2 kroner a day to feed the entire family. That wasn’t even enough for a servant in a time when only the poor and dispossessed did the rough housework on their own.

It says a lot about Lars Emil Bruun that he even used this difficult time to learn. He essentially became an apprentice again, working for room and board on an estate in southern Denmark, where he gained insight into the most modern techniques for butter and cheese production at that time. The detailed knowledge he acquired there would benefit him later.

Starting His Own Company

In April 1880, Lars Emil Bruun found a new position in the butter business of C. E. W. Kramer and Wilhelm Bagger. However, Kramer, with whom Bruun got along well, died in 1882. Bruun did not get along with Bagger, so he decided to start his own company, “The Copenhagen Preserved Butter Company.” In fact, he found two investors for this venture: a former farmer and a wholesaler.

Bruun had a loan of 60,000 kroner to work with, though it wasn’t a lavish amount. It was just enough to rent inexpensive premises and buy butter, which Bruun himself packed into cans with the help of a laborer and a cheap assistant.

Once again, Bruun faced bad luck: his two investors died unexpectedly within the first seven months. The death of the wholesaler was particularly tragic: he cut himself on an opened butter can and died of blood poisoning. The heirs terminated Bruun’s loan and demanded their share of all profits earned so far within six months.

As soon as Bruun learned of this, he disappeared abroad, causing wild rumors in Copenhagen. Upon his return, he found his beloved mother on her deathbed. Bruun hurried to Ordrup to be by her side and bury her. Here, Lars Emil Bruun’s incredible tenacity showed: instead of being paralyzed by grief, he traveled around the country to buy all the butter he could get. It turned out that his trip abroad had been to secure orders. The young man had a full order book, which he “only” had to process. Within the three summer months of 1885, he earned enough to pay off his investors’ heirs, buy the family villa in Ordrup from his father, and build enough capital to continue his business.

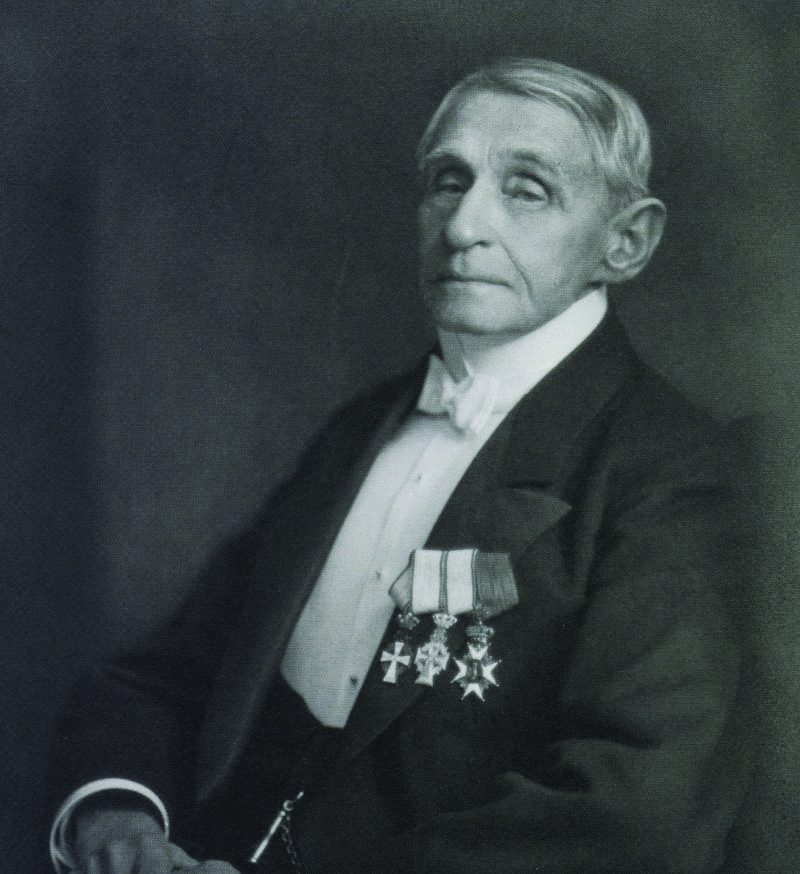

Rising to Better Circles

Lars Emil Bruun was hardworking, skilled, reliable, and knew the industry better than anyone else. Under his leadership, “The Copenhagen Preserved Butter Company” became one of the leading exporters of Danish butter. In 1895, the company employed over 200 workers during the summer season, packing over a million cans of butter. By 1900, Bruun declared an annual income of 910,000 kroner. In 1917, according to his tax return, he possessed a fortune of 18 million kroner.

No wonder the higher society took notice of this successful entrepreneur. He was invited to events and involved in cultural projects. Bruun was one of the founding members in 1885 of the “Coin Collectors’ Society of Copenhagen.” This was an honor back then. Such a coin society had at most one or two dozen members, all of whom were wealthy. A high membership fee and the guarantee required for joining prevented workers or employees from becoming members.

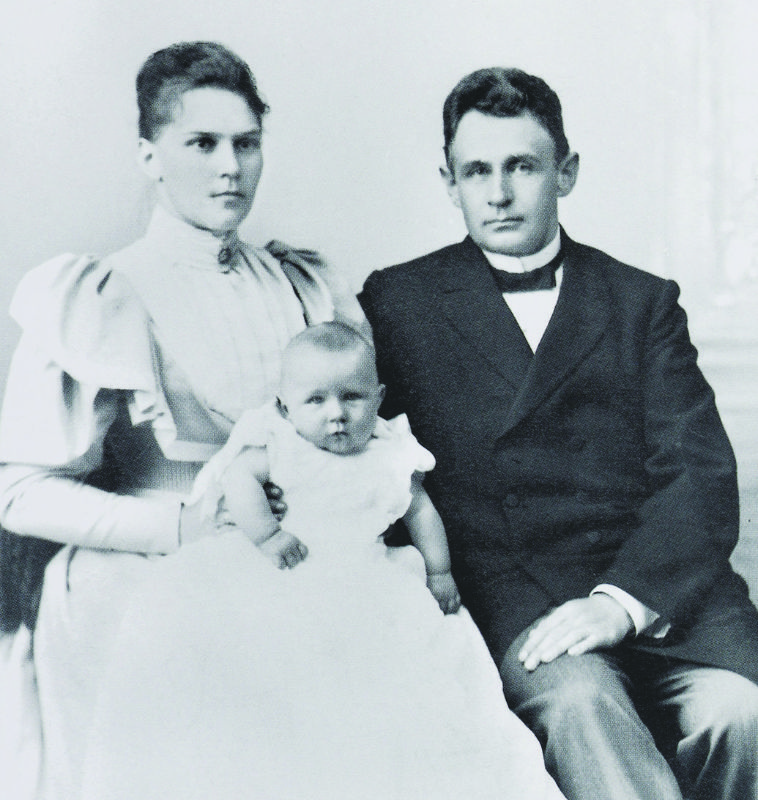

The down-to-earth Bruun was probably fascinated and flattered by all the attention he was now receiving. Did he fall in love with Ingeborg Bauditz because of this? After all, as we know from a letter dated May 26, 1886, he had been searching for a suitable wife for a long time. Lars Emil Bruun was 40 years old when he walked down the aisle with 28-year-old Ingeborg Bauditz on May 3, 1892. She came from the high society in Copenhagen. Her maternal grandfather—a merchant and politician—was influential and wealthy. Her father came from an old Danish military dynasty with excellent connections to the royal court.

A Peasant Remains a Peasant—At Least to Copenhagen Society

Was it love that led Ingeborg to say yes? Or did she marry Bruun because she had no other choice? We will never know. A photo taken in 1897 already hints at the couple’s estrangement: Ingeborg stands facing forward, without paying attention to her husband, who is almost desperately holding onto her arm.

How unhappy the marriage was is evidenced by a letter from Lars Emil Bruun on their eighth wedding anniversary. In it, he says that his wife never took an interest in his business. She only sought her own pleasure, putting his reputation at risk due to all her male acquaintances. Being a child of his time, Bruun blamed his wife and demanded that she fundamentally change: “I myself am unhappy, and only you can change everything if you want to; but you must completely change your behavior, otherwise it will not work, I assure you that. I send you these lines to ask you to stop and change for me and your children; otherwise, it will be a terrible catastrophe for me and the children, remember that.”

On the occasion of Lars Emil Bruun’s business’ 25th anniversary, his employees had a medal minted as a tribute to their celebrated employer. The medal was accompanied by a beautiful, calligraphic letter of congratulations. (1908). Photo: Stack’s Bowers Galleries.

Perhaps it was insurmountable differences in mentality that separated Lars Emil Bruun from Ingeborg. He came from the simplest background; she was a product of the better Copenhagen society. Lars Emil Bruun neither shared the prejudices of the old-established wholesalers, nor did he have a sense for their moral concepts. What were they to think of a company boss who personally ensured that his illegitimate sister found a good position? Who took the time to personally write a condolence letter just because the wife of one of his many subordinates had died? How much empathy Lars Emil Bruun showed for his staff is evident from excerpts from his diaries. This was not common. And then there was, of course, the incident that split the numismatic society.

It all began with the board’s decision in 1894 to issue a medal. This was an economic gamble, as even if each of the 24 members bought a medal, the costs for design, die cutting, and production were far from covered. Therefore, some members, including Bruun, promised to purchase not just one, but several medals. But even that didn’t help. The sale turned into a financial disaster. The association’s treasury was facing a dramatic loss. In this situation, the association’s president, Vilhelm Bergsøe, went to Bruun. What exactly happened during that meeting, we will probably never know. Bergsøe told everyone that Bruun had refused to buy ten medals at 5 kroner each, which he had agreed to. Bruun remembered the visit very differently. He confronted Bergsøe about it. Bergsøe avoided the unpleasant argument and called the wholesale merchant Bruun a “peasant.” Bruun retaliated by indirectly calling Bergsøe a liar. An incredible scandal! Neither of them backed down. A heated exchange of letters ensued, leading to the entire board resigning. The association existed thereafter in name only. And all because of 50 kroner—a lot of money for an apprentice, nothing for an industrial magnate.

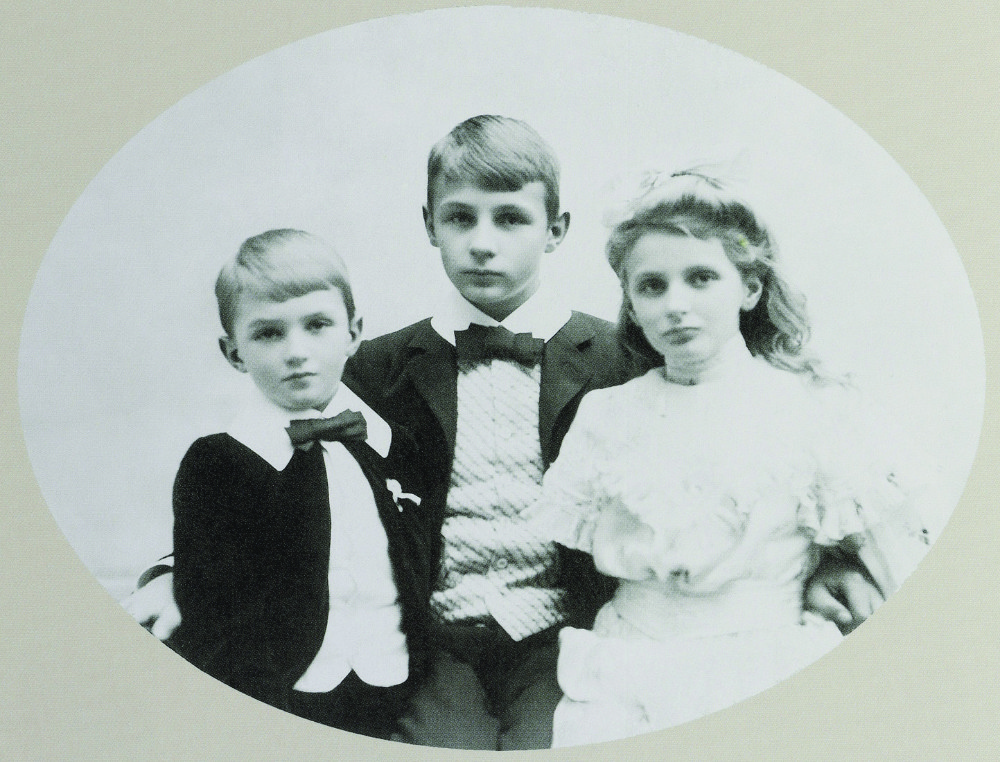

What might Ingeborg have thought about this? A more understanding wife might have explained the rules of her social class to her husband. But would Lars Emil Bruun have listened to her? The fact is that the marriage was dissolved in January 1906. Custody of the three children—Eivin, Hans, and Eleanor—was awarded to the father.

New Marriage, New Happiness

On October 14, 1908, Lars Emil Bruun married for the second time. This time, his bride did not come from high society, but from the same social class he himself belonged to. The 28-year-old Pauline Antoinette Juliane Kjær, affectionately called Tony, was the daughter of a landowner. In a letter, Bruun expressed his hope “that this marriage will be happier than my first and that God will grant me the peace for the rest of my life that I so deeply long for.”

A European Tragedy

In fact, the marriage to Tony was a very happy one. Lars Emil Bruun’s travel diaries bear witness to a deep mutual affection and consideration. However, the much longed-for peace was not granted to the successful merchant, nor to all the other citizens of Europe. The brutal battles before, during and after the First World War took the life of his eldest son, Leofred Eivin Bauditz Bruun, who was born on March 2, 1893.

The father did not have to blame himself for not taking care of his child. Although he sent his 13-year old son to the well-known boarding school in Birkerød after the divorce, the family would reunite once a year during the winter for three months to spend the holidays together on the French Riviera. Thus, the fate of Eivin is one of the great tragedies in the life of Lars Emil Bruun. His son was not a born businessman like his father but was passionate about the military. At 19, he eagerly and unpreparedly volunteered for the First Balkan War. Fortune favored him: he did not have to fight in a major battle. Instead, the dashing Eivin fought in smaller skirmishes with Turkish troops and Albanian bandits; he enjoyed the displays of appreciation from the local population and dreamed of a heroic battle against all evil.

Upon his return, he pursued a career in the Danish Army. Thus, he was spared the brutal reality of the trenches during World War I. Denmark was neutral; the Danish army was not deployed. In 1918, Eivin was discharged at the end of the war. But in January 1919, without consulting his father, he hurried to Estonia to defend Tallinn, a city with close historical ties to Denmark, against the Bolsheviks. As fate would have it, Eivin sustained a fatal injury during a “heroic” mission. At great personal risk, two medics rescued him from being captured by the Reds. It was in vain. Eivin died after five days in a field hospital. All that was left for his father was to bring the body home at his own expense, costing 822.75 kroner. The local newspaper of Gentofte reported on Eivin’s funeral: the coffin was draped in the Danish and the Estonian flag. It was almost hidden under all the wreaths from Estonia, Latvia, and Denmark. Did it ease the father’s pain that his son was celebrated as a ‘Danish hero’ by the media?

We know that both father and son believed in military heroism. This is evidenced by the large donation Bruun made to the French town of Pont-à-Mousson. The location was carefully chosen. Pont-à-Mousson was not just any town. Its residents had been awarded the War Cross with Palm by the French government in 1921 and the Cross of the Legion of Honour in 1922. During the First World War, fierce battles had raged here, costing nearly 7,000 French and German lives. The civilian population of the town temporarily shrank to less than 50 residents. Lars Emil Bruun handed the mayor of Pont-à-Mousson a substantial donation to establish a children’s home for the children of the slain civilians, which he visited in person.

An oil chalk drawing of L. E. Bruun by Danish artist Peter Severin Krøyer. Photo: Stack’s Bowers Galleries.

The 1920 Trip to the USA

Since Lars Emil Bruun could afford it, he had undertaken extensive travels with a varying agenda. He visited the agents and customers of his butter empire personally, got to know the wide world, and purchased coins from dealers around the globe. We have detailed travel diaries from two major trips he took with his wife Tony. They bring us closer to the man Lars Emil Bruun and testify to his numismatic passion.

During his trip to the United States, he of course visited the collector Virgil Michael Brand, who is still very well known today. In his diary, Bruun describes the peculiar circumstances under which Brand lived in his brewery, which had been shut down due to the Prohibition. Somewhat condescendingly, he notes that “the man looked like a small German innkeeper” and mockingly remarks that “his inner self mentally corresponds to his outer appearance.” Bruun pities him for keeping all his coins in the bank vault out of fear that they might be stolen. Therefore, Brand could show him only a few coins, including some extremely rare pieces: 5-Guineas of James II and George II, all in mint state. Ever the selfish collector, Bruun hopes that Brand won’t turn to Danish coins, because “then they would become expensive in the future!”

The Final Years

The somewhat caustic humor that emerges from the records of 1920 may be related to Bruun’s struggle with the early symptoms of his diabetes. Today, we have forgotten the terrible effects this disease had before the discovery of insulin. Those who developed diabetes back then had at most two or three years left. They literally starved, wasting away to the bone, before falling into a diabetic coma and dying.

The turning point came with the discovery by Frederick G. Banting and Charles H. Best in 1921. In 1922, they saved the first diabetes patient in a Canadian hospital. Since February 1923, insulin was also being produced in Denmark. The country was among the first three European nations where doctors used insulin. Bruun also received this treatment. However, it proved fatal for him that this new treatment method had not yet become established in France and Italy.

Bruun did not forgo his usual winter vacation in Monte Carlo. Insulin was regularly sent to him. But in November 1923, the package was lost. The Italian doctors refused to procure a replacement. This refusal cost Bruun his life. He died from diabetic shock on November 21, 1923, at the age of 72. His body was transported to Gentofte, where he was interred in the family crypt on December 27, 1923.