Money Talks – Art, Society & Power

On August 9, a new exhibition will open its doors at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. “Money Talks: Art, Society & Power” delves into the complex, tense and often humorous relationship between art, money and society.

The exhibition will feature more than 100 objects from across the globe, from coins and banknotes to artworks by Andy Warhol, Guerilla Girls, Grayson Perry and Banksy, to the new phenomenon of crypto currency and NFTs. The exhibition will explore our complicated feelings about money – from disgust to desire – and reveal the art hiding in notes and coins that we rarely consider.

The “Hallifax Bowl”. Silver-gilt bowl set with ancient Roman coins and early 16th-century replica medallions, probably made in Eastern Europe. Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

The exhibition offers an insight into the painstaking process and marvellous creativity involved in the production of money across the globe and throughout history. Sculptors, engravers and calligraphers, graphic designers, painters and photographers have made impressions on everything from ancient coins and ingots to modern bank notes.

The exhibition explores the image of rulers found on currency, from Emperors like Nero, right up to the present. The show opens with a very rare set of coins with a complicated design process: those planned for Edward VIII. Edward’s challenging brief to his designers was to produce a ‘modern’ coinage. He also demanded that he be depicted facing left, believing his features to be more favourable on that side. Tradition held that new coinage depicts the monarch facing the opposite way to the predecessor, and it was Edward’s turn to face right. Neville Chamberlain, Chancellor of the Exchequer, ruled that the King was to have his wish. After heated negotiations over the final designs, the King abdicated, so the coins exist only as “patterns”.

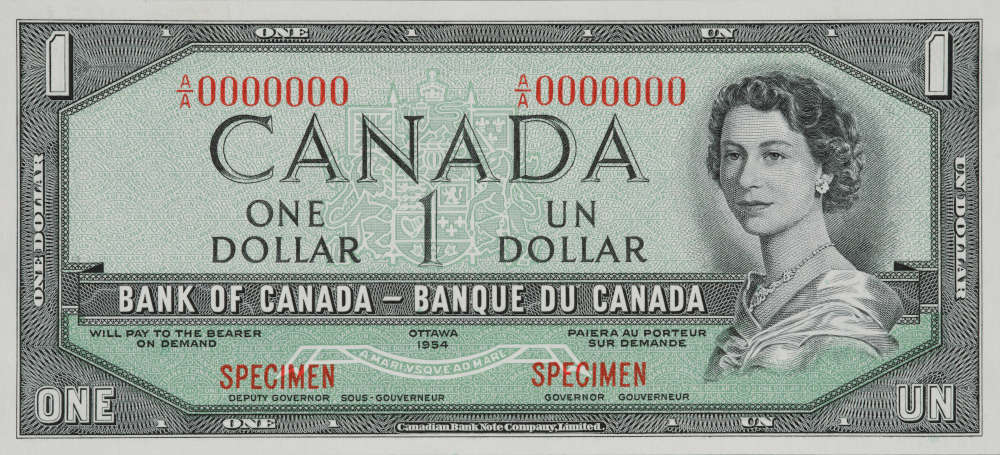

Money’s power to turn an image into an icon is nowhere clearer than the example of Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022). Across the globe, a vast population were familiar with the Queen through her monetary portraits. The first notes bearing her likeness were issued in Canada in 1954, based on Yousuf Karsh’s pre-coronation photograph. Her Majesty’s intricate curls of hair acted as a security feature against counterfeits. But a conspiracy theory soon caused controversy: on close inspection (and with some imagination) a grinning devil’s face appears in the hair behind the Queen’s left ear. The notes were redesigned and a new issue, “exorcising” the devil, came out in 1956.

Arnold Machin (1911–99) A version of the “Dressed Head” sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II, 1966 Plaster cast relief, 46.5 x 41.5 x 4 cm. The Postal Museum.

Visitors will also see one of the most reproduced artworks in the world – the plaster bust of Elizabeth II by Arnold Machin made in 1966 which appeared on billions of postage stamps as well as money.

Koloman Moser (1868–1918) Draft artwork for 50-crown note for the Austro-Hungarian Bank, 1902 Gouache and coloured pencil on graph paper, 11 15.2 x 10.4 cm Money Museum of the Austrian National Bank.

Just like fashion, architecture and the visual arts, the design of money has been influenced by art movements and trends. In the early 20th century, Art Nouveau and Art Deco left their marks on money both in Britain and abroad. Viennese “avant garde” artists were the movement’s chief protagonists. The exhibition will show banknote artwork by Franz Matsch, Gustav Klimt and Koloman Moser. Their designs were typical of their wider work.

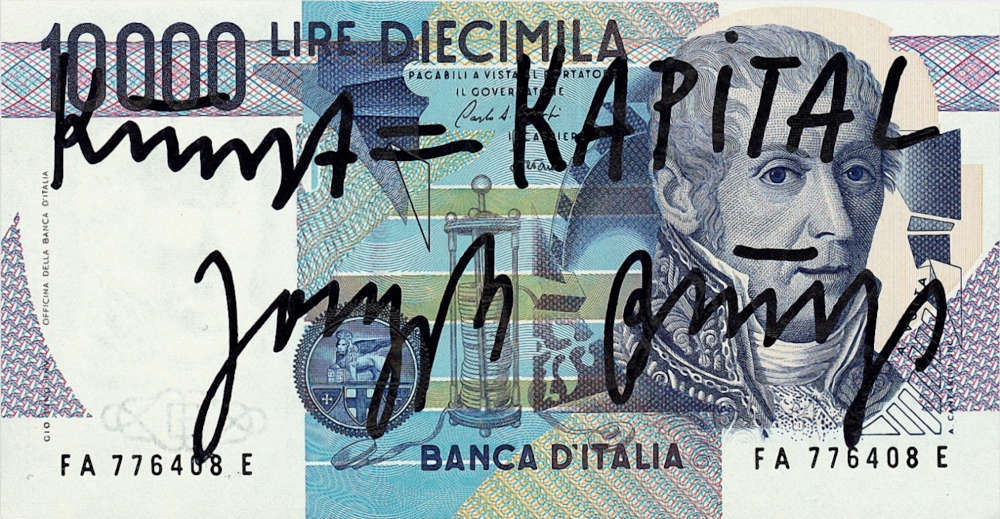

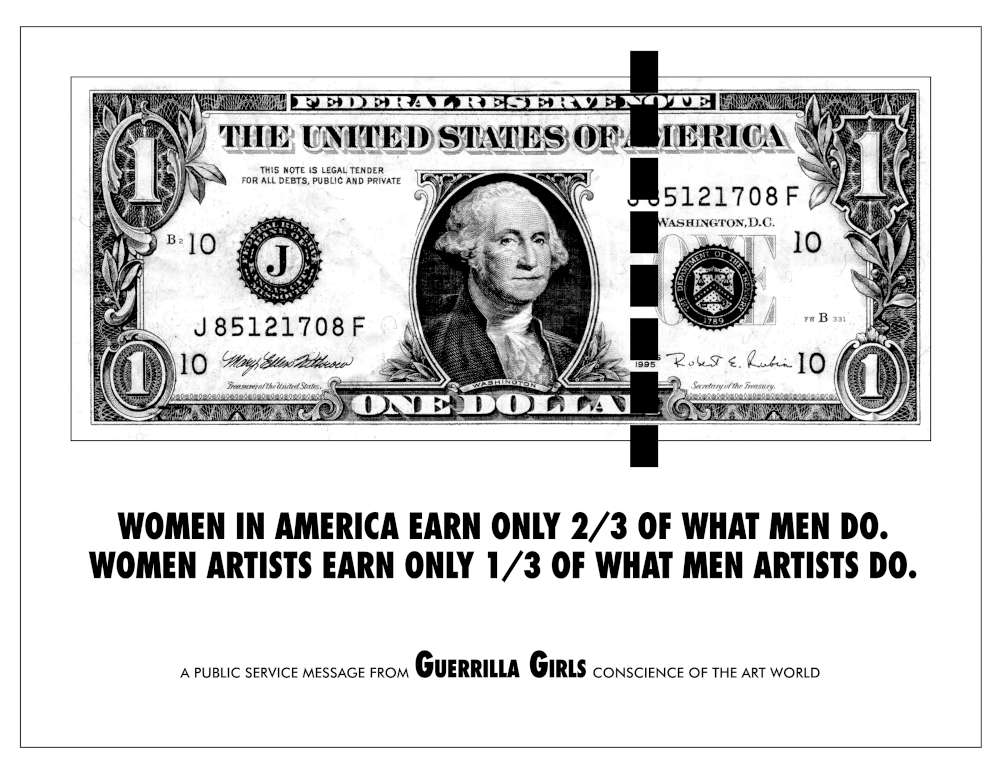

The exhibition continues by examining the depiction of money in art, contrasting western and eastern traditions. In historic European artworks, money typically has an image problem: we find scheming usurers, grasping officials and the dissolute rakes of Gillray’s prints. The tradition from the Indian Subcontinent and further east, though, treats money with a happier attitude: in many works money stands for prosperity, plenitude and fertility.In the hands of modern artists, money can be a provocative lens and even a medium itself to address politics and social values. The defaced note by the German artist Joseph Beuys is a commentary on the relationship between art and money and how it can be subverted. In the 1970s, Beuys used paper notes by adding the phrase “Kunst = Kapital” (“Art = Capital”) alongside his signature, making a statement on the commodification of art. Predictably, the notes themselves became collectable and more valuable than their denominations. Later, Guerilla Girls’ 1985 work, Women in America Earn Only 2/3 Of What Men Do, is an enlarged dollar bill marked with a dotted line two thirds of the way across. Banksy’s Di-faced Tenner (skit note) (2004), which replaced the head of Elizabeth II with the face of Princess ‘Di’, satirised their famously thorny relationship and the institution of monarchy.

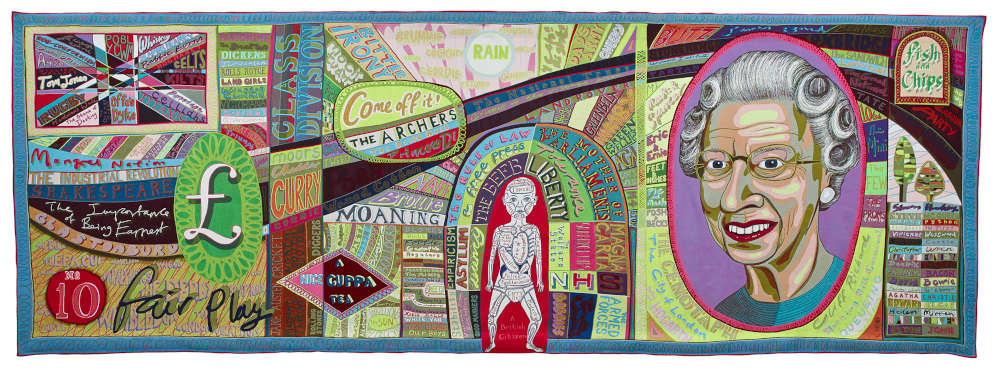

The exhibition will also show Susan Stockwell’s spectacular Money Dress (2010), a sculpture of a Victorian dress made entirely from worldwide banknotes. The artist’s original intention was to use only notes depicting women, but as these are so rare, they are confined to the collar, belt and cuffs. And Grayson Perry’s monumental Comfort Blanket (2014) is a tapestry based on a £10 note, that explores the relationship between British national identity and capital.

The final section of the exhibition considers the future of money in the wake of technological advance. The line between money and art has become blurred thanks to blockchain technology which is behind both cryptocurrency and Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). The exhibition will feature a new NFT commissioned by the Ashmolean for the show.

Dr Xa Sturgis, Director of the Ashmolean, says: “Although money is not usually considered an artform, the two have interacted and informed each other in many ways and from the beginning of time. Including a range of dynamic and striking objects, Money Talks challenges our views of how money comes to be in our pockets and what happens to it and with it.”

The exhibition will run from 9 August 2024 until 5 January 2025.

![James Gillray (1757–1815) MIDAS, Transmuting all into [GOLD] PAPER, 1797 Hand-coloured etching on laid paper, 25.9 x 35.9 cm New College, Oxford. James Gillray (1757–1815) MIDAS, Transmuting all into [GOLD] PAPER, 1797 Hand-coloured etching on laid paper, 25.9 x 35.9 cm New College, Oxford.](https://new.coinsweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024KW28aNews02EN_07.jpg)