Springtime in Turkey – Part 7

by Ursula Kampmann

June 6, 2013 – Given the number of tourists about the place, one could be forgiven for thinking that pretty much everyone in the world has already walked along the Curetes Street of Ephesus. And we were taking in Ephesus on a quiet day too, relatively speaking …

Sunday April 28, 2013

After one last elaborate breakfast and a friendly send off from the woman who runs the Hotel Erguvan, we said our goodbyes and set off to continue our travels. We were headed for Ephesus, the heart of tourism on the Turkish west coast. And where were we planning to find accommodation? Well that’s easy – in Kusadasi, along with hundreds of thousands of other tourists who flock there every year to go swimming.

But getting there didn’t prove easy. From Izmir, we had to get on the highway. I had figured I had a pretty good grasp of most road tolling systems in the world, but in Turkey, I failed miserably. There was no ticket to pull out at a barrier gate, just as there was no obvious tollbooth where you would pay. With an incredibly bad conscience, we passed the last toll post, but it was only when we realized that the police were lurking behind the station that we really got nervous. As a precaution, we slowed down and stopped, and I got out of the car and I ran over to the police car to at least show my good intentions. The policeman smiled and calmed me down. He didn’t make any moves to arrest us. He also couldn’t really tell us what we should actually have done toll-wise, since he spoke nothing but Turkish. And my Turkish is rather limited. Later, after searching long and hard in my guidebooks, I finally came upon a bit that explained that you’re supposed to buy a ticket from the Turkish post office before getting onto the highway, and that ticket is then automatically charged. In any case, we hadn’t come across any post offices during our entire stay, and I highly doubt that the postal workers speak foreign languages well enough to understand what we would have been asking for. So, it seems that if the Turkish are looking to collect road tolls from everyone, including ignorant tourists like me, they’re going to have to consider a simpler system.

We passed Selcuk first, then continued along the coastal road and arrived in another world. The sea alone isn’t enough – nowadays tourists are looking for more than just a little salt water. The secret is the ‘aqua park.’ With a multi-coloured plastic backdrop, today’s modern beach-goer gets to swim among dolphins and have their senses tickled by sliding headfirst through miles of tunnels into the water. Or at least that’s what the billboard at the side of the road proclaimed. Kusadasi has ‘Adaland’ ‘one of the ten best ten aqua parks in the world,’ says the New York Post. From the highway, you can see three towers, which look amazingly like St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow (the Adaland website is in three languages: Turkish, English and Russian). At Adaland, you can get close to crocodiles and feed stingrays by hand. There are dolphin and seal shows. And the price for this pleasure: 15 Euros. Swimming with the dolphins will cost you 100 Euro. We decided to spend our holiday budget elsewhere.

We stayed in what was once a pearl of the Turkish seaside. The slightly dusty, formerly plush hotel had previously played host to the Queen of England, the Belgian and Swedish royal couples, the Crown Prince of Spain, as well as well-known politicians like Jimmy Carter and Lech Walesa. That was back in its heyday, of course, when the hotel on this beautifully situated cape was still new and gleaming. The grand dame of Turkish tourism has gotten on a bit in years since then, and in the off-season, you can even catch a glimpse of some German tourists there, in a filthy car, just like the one we were driving, hmmm …

Its charming appearance almost makes you forget how the vast influx of people and hotel construction has spoiled the once beautiful coast. We took it in, and were also looking forward to a siesta in the huge hotel park. But before we did this, we decided we would drive to Ephesus. There are two quiet times to visit: midday, and late afternoon.

According to Myth, Ephesus was founded by the Athenian prince Androklos. There are actually traces of a first Greek settlement dating back to the 11th century BC, but the city only really becomes tangible from an archaeological standpoint later, in the 9th century, when the first Artemision likely came about. In the 7th century, Ephesus was a thriving Greek city ruled by tyrants. It’s during this period that the first coins could have dropped, such as the famous stater of Phanes, which because of its depiction of a deer is associated with Ephesus.

Sometime in the 6th century, Ephesus came under the control of the Mermnadae. First, a relative of the King of Lydia ruled, and Ephesus is later said to have been conquered by Croesus. There’s a desire to link the electrum coins with the lion’s paws with the Lydian influence. In any case, Croesus was a great patron, and is to have provided considerable funds towards the construction of the Artemision. We don’t know what the city looked like back then, since its remains are completely buried under alluvial land.

The Persians conquered Ephesus in 546/5. Everyone seemed to be on good terms with one another too, as Ephesus remained neutral during the Ionian revolt. Only when Athens was established as the new leading power did Ephesus switch fronts, only to return to the Persian side during the Peloponnesian War. The city fathers of Ephesus seem to have been masters of plodding on and muddling through.

At any rate, they told Alexander the Great that they did not need his help to reconstruct the Artemision, which had been set on fire in 356 BC by a certain Herostratus. They feared for their independence. That this fear was justified is shown by the actions of Lysimachus: When he became ruler of the city, he resettled the residents to where today, millions of tourists make their way along Curetes Street.

Sources report that he had the sewer system of ancient Ephesus rendered unusable so that the residents of Ephesus had no alternative but to retreat to the new Arsinoeia– named after Lysimachus’ wife. The new city name did not survive after Lysimachus’ death, however. When the city fell first to the Seleucids in 281, it was again referred to as Ephesus. The Ptolemies arrived around 260, then in 197, the Seleucids, and then in 188, with the Peace of Apamea, the rulers of Pergamum.

When the Attalids died out and the Romans took over Asia Minor as a province, Ephesus became their administrative capital. The governors resided there, and they certainly didn’t make any friends along the way – when Mithradates VI, King of Pontus appealed to all of Asia Minor to rise up against the Romans, Ephesus was there. Eighty thousand Romans and Italians were slaughtered during the Ephesian Vespers, which have become famous.

Ephesus was made to pay for these actions when, in 84 BC, Sulla made it see the error of its ways. The detractors of the Romans were killed, the city plundered, and the territory was downsized. And, of course, taxes for the years 88 through 85 also had to be paid retroactively.

For Arsinoe IV, rival of the famous Cleopatra, Ephesus, or rather the Artemision, became a place of exile. Caesar assigned this detention to her after she had played her part in his triumph. Arsinoe’s fate was sealed following Caesar’s murder, however, and after Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra had come to an agreement – she was executed.

Ephesus’ great heyday began with Augustus. The city recovered from having had its resources completely depleted by all the parties in the various Roman civil wars, and it evolved into one of the most important port cities in the Roman Empire.

The city that countless tour groups visit today is the Roman Ephesus, which was one of the most populous cities of the ancient world. The population is estimated at 300,000, which would be almost as many as in Roman Alexandria. In the 3rd century, however, the port began to peter out. A massive earthquake in the year 262 ushered in an economic downturn that was only slowed because Ephesus became a centre of Christian faith. Tradition has it that this was the last place of residence of the Virgin Mary (and no, we had neither the time nor interest to visit these ruins), and some important councils were held in the city. Shortly before the First Crusade, the Saljuqs conquered the city. And it’s in this context that the little town of Selcuk, which has made it all the way to the modern age, was born. The main mosque grew out of St. John’s Church. Trade flourished, even if it was no longer transacted through the old port. And once trade slowed, there was always piracy. The Venetians in particular had to contend with this problem repeatedly. With the Ottoman victory, however, Selcuk declined in status from successor of the ancient Ephesus to that of a provincial town.

Have you ever tried to study the manners and customs of groups of tourists? As a seasoned practitioner, I can tell you this: it’s easy to predict a group’s path. They all do the same thing at the same pace in the same way. We made up our minds to do things differently. Our first attempt failed, though – unfortunately the highly acclaimed local museum was in the process of being renovated when we tried to visit. Mind you, in Ephesus, there are two entrances by which you can enter it. We chose the lower one, much to the amazement of countless taxi drivers who explained to us that that was impossible, and that for very little money they could take us to the correct entrance.

Indeed, it was very possible. We entered the excavation site right around the theatre. Its size alone is impressive. The first modest construction is said to have started around 100 BC, and was then renovated and expanded several times during the Imperial Era. Therefore, when the Apostle Paul found himself confronted with the famed demonstration of silversmiths (‘Great is the Artemis of Ephesus’), the backdrop was considerably more modest than it is today.

The grand avenue that led to the former port area is, unfortunately, blocked off. The Arkadiané is over a half kilometre long, was likely built as early as the late Republican Period (albeit, more modestly) and takes its present-day name from the Emperor Arcadius (395-408), who outfitted and restored it magnificently. Its famed streetlights however, mentioned by every tour guide, have only been there for a very short time. They were installed in the 6th century, and nowhere is it mentioned how long they were in use.

Taking a look at how other nations travel always proves educational. Japanese guidebooks seem to be suggesting nowadays, that one might want to wear gloves in order escape the country’s dirt. The mouth is completely covered against germs. And while German and Russian tourists tend to run around in as little clothing as possible, even in the most inappropriate of contexts, in an attempt to make the most of every single ray of sun, the female Japanese tourist covers herself up discreetly and uses a collapsible parasol.

From the theatre, you come to the ‘Tetragonos Agora,’ which is, incidentally, not an archaeological auxiliary term, but rather a name that has been recorded in inscriptions. Trade had its place here, a fact that can perhaps be grasped by the many small, divided shops.

Whereas you’re almost all alone at the Agora (all groups just go past it), the small area in front of the Library of Celsus is the focal point of all tours. As someone from Munich, one can’t help but think of Oktoberfest, and particularly that time between 6 and 7:00 pm when all the beer tents are totally overcrowded. Tour guides shout in every language, some of them a bit louder, others even louder still. A thousand times a second, a picture is taken of the library, and every single visitor seems to think that theirs will be the best and most amazingly interesting one to show to the folks back home. You have to keep your flight instincts in check when standing in front of the library if you actually want to be able to take in and admire its magnificent, detailed decorated facade. The Library of Celsus is the highlight for group tourists. But very few are interested in who Tiberius Iulius Celsus Polemaeanus actually was. He actually came from Sardis. His political career began under Vespasian, and it led him all the way to the office of Consul, followed by a position as Proconsul of the Province of Asia. Ephesus was the administrative centre, and Celsus liked it there. He settled there even after his term and became a great patron of the city. His endowments were so significant that the Ephesians elevated him to a new founding hero, which meant that he was granted special permission to be buried within the city walls. He rests under his library, which must be viewed as a tomb that offered its visitors a special service.

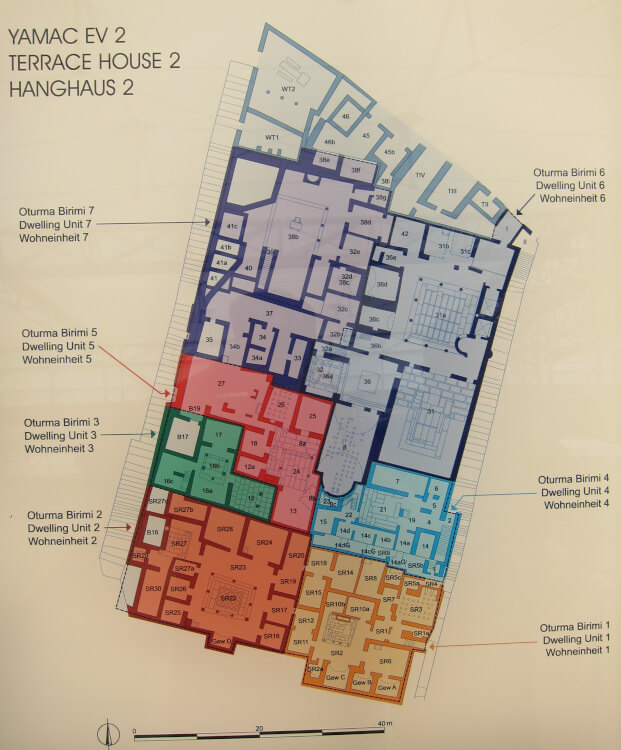

Luckily, the hillside houses (the so-called ‘terrace houses’) just next to the library ask a fairly steep entrance price, which is on top of the (already also not cheap) main admission price. This means that all tour groups that cover Ephesus in an hour and a half don’t set foot in here. It’s quiet here – something that you’ll gladly pay over 10 Euros for after the hustle and bustle in front of the library.

Via a glass footbridge, you walk through splendour that, from the outside, is hard to imagine existed – mosaic floors, murals and marble panelling, all of it in overlapping rooms, such that it’s hard to imagine how the different living spaces were separated from one another.

This terrace house, however, gives us a good idea of how the Roman upper class lived in in a big city.

Although we tend to like thinking of the Romans living in secluded villas, visiting this excavation quickly makes it clear that what we’re dealing with here was more of an apartment block type situation, albeit an incredibly luxuriously outfitted one. Then as now, space in a city was a great luxury that only very few people could afford.

We spared no effort to get you this photo!

The entrance to the hillside houses is directly on the so-called Curetes Street, which archaeologists also tend to refer to as ‘Embolos.’ We have to imagine this street as a sort of main artery through the city on which the most important representative structures were located, including the Temple of Hadrian, which certainly was not the temple where the Neocoria for this emperor was located. It may have been more of a private cultic site, but this is just a personal hypothesis. Just what purpose the structure served forms the basis of a research project currently being undertaken for the Austrian Archaeological Institute.

When faced with the structure for Domitian, you get a better concept of just how big a Neocoria temple should be. There’s a little story to go along with it that I feel is very typical with respect to the way of thinking of the upper class in Asia Minor in Roman times. This type of Neocoria temple was, in fact, an important source of civic pride, much like the Olympic Games are today. It was, of course, incredibly expensive to maintain a Neocoria temple and it brought absolutely no economic benefit, but as a politician, one could bask in the recognition of all other civic politicians who had to come to the Temple in Ephesus for an assembly of the Koinon of Asia. These moments of pride more than justified the thousands of denarii and aureii that had to be spent.

Now, with respect to the Neocoria Temple, Ephesus was somewhat glossed over during the 1st century. Pergamum had had one since the time of Augustus, and Smyrna got one under Tiberius. But it was only Domitian who relented. Construction of the monumental structure began enthusiastically – and then pretty much fell flat on its face because – as I’m sure you remember – following Domitian’s death, the Senate passed damnatio memoriae on his memory. Now Ephesus had a wonderful temple whose God was no longer allowed to be mentioned. Pretty silly. But they found an alternative: they rededicated the temple. The Flavian Dynasty was now worshipped instead of Domitian.

Is all of this making you tired? We certainly were. A quick look at the clock told us that we’d now been roaming around the excavation for almost five hours. We dutifully had a quick look at the government buildings, the bouleuterion and the Prytaneion, and then realized that too many stones in one day are unhealthy.

Totally exhausted, we sat with a glass of pomegranate juice in the square in front of the entrance to the excavation of Ephesus and marvelled at the goods that were being sold there.

There were fake watches covering all the top brands …

… and the infamous tourist fakes, which some people still believe are real coins.

Somewhat restored, we headed off to see just one last thing – The Sanctuary of Artemis at Ephesus. It’s actually located right on the road leading from Selcuk to the excavation, but is still quite hard to find. You have to take a sharp 90 degree turn on the highway, and the arrow towards Artemision is really only visible to the most eagle-eyed of tourists. We drove along said highway twice in one direction and once in the other direction before we finally managed to spot the entrance just in time.

We were rewarded with an idyll where the storks had built their nests and the frogs croaked happily. There were no tourists to be seen. By now, of course, it was around dusk.

What’s more, for us numismatists, the Artemision is THE key site. It provides us with the only chronological benchmark by which we can attempt to date the early electrum coinage. During the excavation, a small number of electrum coins emerged from under one of the fundaments, and with their help, we try to solve the mystery surrounding the beginnings of coinage. This isn’t easy though, since the excavation took place some decades ago, and the publication leaves more questions unanswered than answered.

At any rate, today the coins give us a much better idea of what the Temple of Artemis, once one of the Seven Wonders of the World, must have looked like. This cistophorus shows us the magnificent column drums, decorated with Frisians. Also clearly visible is the door in the temple roof, from which a priestess dressed as Artemis would appear before the awed crowd during celebrations of major festivities.

Gone. Gone and lost forever. A Spanish tour group interrupted our melancholy reverie. It got loud again. Very loud. We retreated.

Join us for the next leg of our journey as we visit the almost completely destroyed Miletus and its important shrine, the Oracle Temple of Apollo at Didyma.