The Coin Hoard of Merishausen

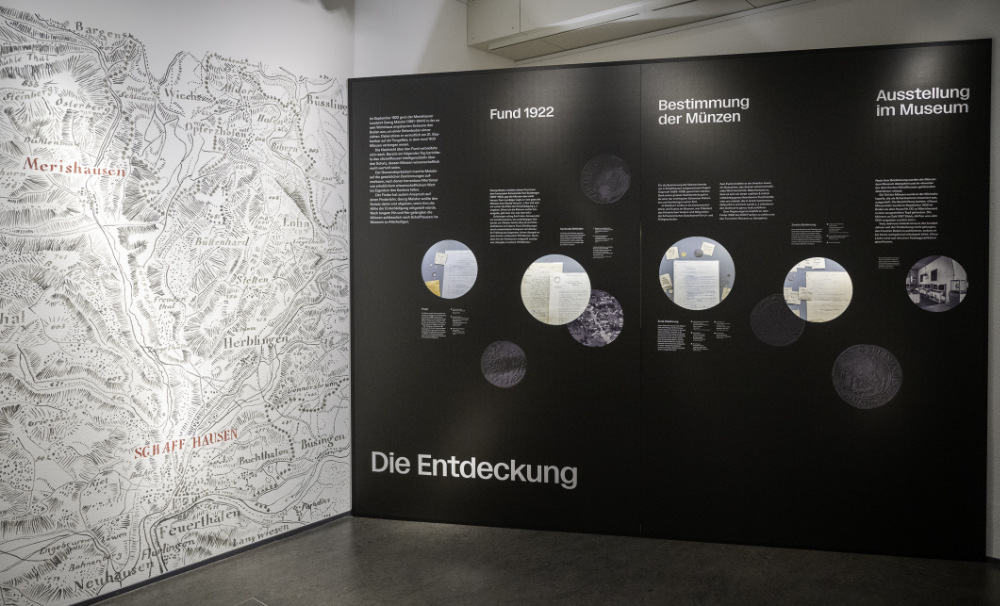

From 15 March to 19 October 2025, the Museum zu Allerheiligen in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, is mounting a special exhibition on the coin hoard of Merishausen, presenting the results of research on this interesting ensemble to the public.

Content

It all began in September 1922. At the time, a farmer from Merishausen called Georg Meister wanted to lay a modern concrete floor in his barn. In order to do so, he had to dig up the ground and came across a jar containing about 1,087 gold and silver coins. News of the find spread quickly. As early as on 22 September, the newspaper “Schaffhauser Intelligenzblatt” reported the find, assuring its readers that it was of great scientific value.

“Of scientific value” was important, for the Swiss Civil Code of 1912 distinguished between “normal” treasures, whose value was more or less shared between the finder and the land owner, and “antiquities of scientific value”. In the latter case, the canton became the owner of the hoard, while finder and landowner were entitled to appropriate compensation.

Evidence of the first scholarly examination of the find by Eugen Tatarinoff. Staatsarchiv Schaffhausen, RRA 5/6 and Museum zu Allerheiligen Schaffhausen. Photo: Julius Hatt.

Georg Meister had his own idea of what appropriate compensation looked like. He did not trust the Schaffhausen officials and cleaned the material himself – in a very unprofessional way – in order to get an appraisal. Unfortunately, the first “expert” gave him too much hope. That is why it took months and several additional expert opinions until Meister agreed to hand over the hoard to the canton in 1924 in return for a “finder’s reward” of 3,000 Francs. The antiquarian Eugen Tatarinoff drew up a twelve-page inventory of the find, organised the coins into small bags and provided the first dating of the hoard by stating that it was buried after 1554.

A New Examination a Century after the Discovery

At the time, the find was transferred to the newly founded Museum zu Allerheiligen, where it remained for almost a century – sometimes on display, sometimes in the archives. Then came Adrian Bringolf, the newly appointed curator of the numismatic collection of the Museum zu Allerheiligen, and decided to make this hoard the subject of his master’s thesis. After all, the coins had been inventoried according to the latest standards, but had never been scholarly analysed – despite the fact that the size and value of the Merishausen hoard makes it one of the most important finds in the southern Germany-Swiss region!

It contains 45 gold coins, 20 talers, 6 half talers and over a thousand smaller silver pieces. Most of the pieces come from the southern German-speaking areas, from Schaffhausen to Salzburg, from Constance to Bavaria and beyond. The regions where silver was mined, such as Hall or the Ore Mountains, are particularly well represented. About 30 coins are from Italy. With a few exceptions, the gold coins are French. One coin from Seville in Spain, one from Lisbon in Portugal, one from Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands and one from York in England travelled the furthest.

What Was the Hoard Worth at the Time It Was Hidden?

Adrian Bringolf puts the book value of the entire hoard at 6,900 kreuzers of account, or 115 guldens of account. The gold coins accounted for two fifths of the total value, the multiple silver coins for another fifth, and the more than thousand small silver coins for the last two fifths.

By the way, you could have bought about 5,500 litres of wine with 115 guldens in 1554 – or a vineyard, maybe even a small house in Merishausen. After all, a house in Schaffhausen’s Brudergasse street changed hands for 195 guldens in 1523.

The Merishausen coin hoard was therefore of considerable value, especially when keeping in mind that this was a time when only a fraction of daily business was conducted in cash.

Swiss mercenaries in the Battle of Novara. Glass painting around 1530. Bern History Museum. Photo: KW.

Did a Mercenary Own the Coin Hoard?

A total value of 115 guldens of account in the form of gold pieces, multiple and fractional silver coins representing various denominations from different regions with years between 1510 and 1553, the most recent four pieces being from 1554 – is that what the hoard of a merchant looks like? Adrian Bringolf does not think so. He put forward a typical Swiss interpretation, indicating that the composition of the hoard would perfectly fit the savings of a mercenary. Archival documents confirm that the inhabitants of Schaffhausen and the surrounding area liked to earn extra money as travelling mercenaries. Junker Spiegelberg, for example, would fit the description. He took part in the Battle of Pavia in 1512, was captain of the Swiss Confederates in the campaign against Ulrich von Württemberg in 1525, and recruited mercenaries for the King of France. Spiegelberg died in 1554 – the year in which the most recent coin of the hoard was struck.

Of course, Adrian Bringolf knows that we cannot be certain. But it is a nice mental exercise that allows us to better understand how the Merishausen hoard came together.

View of the exhibition “The Coin Hoard of Merishausen” in the Museum zu Allerheiligen / Schaffhausen. Photo: Jeannette Vogel

An Exhibition as the Result of Academic Research

For those who want to know more about the coin hoard and would like to see the original pieces before they disappears into the archives again, the exhibition at the Museum zu Allerheiligen is a must. It will be open from 15 March to 19 October 2025, with a highly interesting programme of guided tours and lectures. If you want to bring the family along, we recommend Sunday, 31 August 2025. There will be a programme for children and adults called “A Small Box for Big Treasures”. And no matter the day, children aged 5 and over can always pick up a craft kit at the museum ticket office to design their own gold and silver coins.