Honni soit qui mal y pense or What exactly was the spintriae’s function?

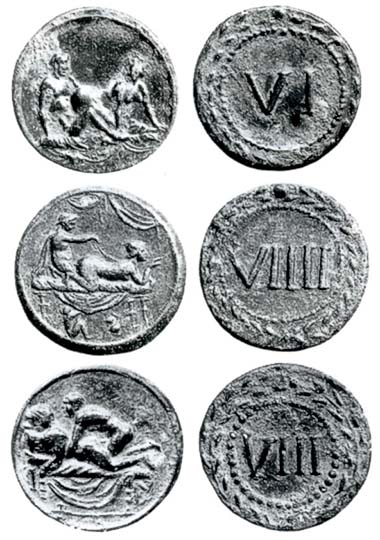

Spintriae are highly popular and expensive collectibles, but what purpose did they actually serve in Antiquity? All three examples come from auction sale MMAG 77 (1992), 144-146.

One has to pay high prices indeed for the so-called spintriae – brothel tokens as one is secretly whispered to. There are experts who know exactly what the function of these objects was: they were bought at the brothel’s entrance. The representations had to be regarded as a kind of catalogue of pleasures on offer in that particular brothel. After choosing a position one went into the chamber whose number the token’s reverse stated and the beauties – which mostly came from exotic countries – were instantly informed about their customers’ desire.

Today, the spintriae have become treasured collectibles. The slightly indecent, crackerbarrel-like odour still sticks to them, to these small works of art which exercise no restraint whatsoever in showing the sexual act.

A bit of research history

Bust of Tiberius. Wikipedia

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tiberius_NyCarlsberg01.jpg

The first person that associated the spintriae with sex was a numismatist called Spanheim who published a treatise on numismatics in 1664. He invented the term “spintriae” for the small bronze pieces that surely were called different in Antiquity. He took it from Tacitus’ Annals which describe the reign of Tiberius; that emperor, which – if we are inclined to follow Suetonius and Robert Ranke Graves, I, Claudius – erotic excesses are alleged to until the present day.

Spanheim’s imagination was exalted when he read a remark from Tacitus (VI, 1) where the old man’s erotic degenerations were described: … “And now were coined the names, hitherto unknown, of sellarii and spintriae, one drawn from the obscenity of a place, one from the versatility of the pathic”; …that was how the spintriae got their name from the catamites of Tiberius.

Today, we see the historical figure of Tiberius from a different angle than Tacitus or Ranke Graves. We know that Tiberius suffered from a dreadful skin rash in his face that restrained him from showing himself publicly. The emperor secluded himself on Capri since he didn’t want to be bothered anymore by the annoying daily business in Rome. Besides, the fact that he took philosophers and jurists with him to his old-age residence doesn’t promote the hypothesis that Tiberius was eager to amuse himself with underage boys. But even in Antiquity, it was impossible to silence malicious tongues.

All numismatists of the 19th century adopted the spintriae’s interpretation as something connected with the sexual act. In his outstanding treatise on Roman numismatics, which is still referred to, Cohen wrote: …”Regarding the use of tesserae and spintriae it is possible that the former served as token or entrance ticket, partly in the theatre, partly in the thermal baths. The spintriae could – as may be deduced from the particular nature of images that can be found on them – as entrance to the Floralia (which were dedicated to the fecundity of the Roman population and involved striptease. author’s note) or to secret spectacles of which the capital had plenty of.”… This puts us right into the heart of the argumentation: such an obscene illustration can only be connected with something where sex is involved. Brothel, orgies or striptease.

Here we have the imagination of the 19th century’s, a time, when Queen Victoria of England – when being prepared for the happenings in the wedding night to come – was told: “Close your eyes and think of England.” The 19th century that provided the fanciest places of amusement with ballet girls whereas on the other hand the upright wife was tied to the kitchen sink and raised the children. Heaven and hell, virtue and sexuality – the spintriae had to be part of one or the other, and that they weren’t connected with something virtuous was obvious by the images they carried.

The true purpose

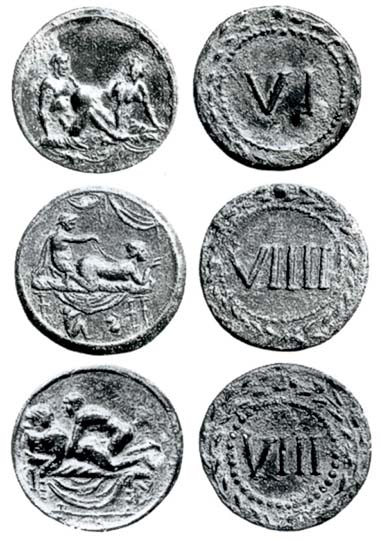

Spintriae could show quite “decent” motifs, too. Here one example from auction sale MMAG 81 (1995), 237, with a representation of the goddess Ceres, perhaps with the facial features of Livia.

What was the Romans’ opinion on that? What purpose did these tokens really served? The pieces’ reverse can give us a little hint. They show numbers from 1 to 16. The single numbers can’t be connected to a particular motif. On the contrary, on close inspection one discovers also very different images of which some were made with the same dies than the so-called spintriae: the portrait of the emperor Augustus with his radiate crown for example, the portrait of Livia and the double portrait of Augustus’ grandsons that the emperor had adopted, Victoria, a temple, the Capricorn. These images can’t be connected with brothels, not by any stretch of the imagination.

The spintriae and the tokens with the portrait of Augustus are dated to the period of Tiberius although some later objects made of bone exist, round or angular shaped, showing numbers on the obverse and Christian symbols on the reverse. Obviously then, the most important thing about these tokens in general wasn’t the “obverse” with their changing motifs but the “reverse” constantly showing numbers. We, too, know objects whose representation can vary but whose value remain the same. I am referring to playing cards. The spintriae may well have had a similar function – as tokens in a game whose rules are unknown to us. In early Imperial Rome, the act wasn’t declared a taboo. Although Augustus went to great lengths to restore the old customs of the forefathers, he failed – even in his own family. Hence, these images were part of everyday life, also suitable to decorate objects of utility such as tokens of a game, the wall of a villa or oil lamps. Private companies manufactured these tokens and distributed them – as they later did with the contorniates.

And the moral of the story is? Nothing is as dirty as what the viewer’s dirty imagination turns it into.

Bibliography:

- T. V. Buttrey, The Spintriae as a Historical Source, NC 1973, 52-69.

- Bono Simonetta and Renzo Riva, Le tessere erotiche romane, Lugano 1981.