An Introduction to Axumite Coinage

By Nick Vaneerdewegh and Lars Rutten

With the collection of Dr. Stephan Coffman, a highly significant ensemble of coins from the great ancient African kingdom of Axum is sold at Leu Numismatik. Learn more about the history of Axum and the often disregarded Axumite Coinage in this detailed article.

Content

According to Manichean literature, the great prophet Mani, living in the 3rd century AD, claimed that four great empires ruled the world: Rome, Persia, China, and Axum. The latter was one of the great African kingdoms of Antiquity, with its eponymous capital, Axum, located in the highlands of what is today northern Ethiopia.

The Rise of Axum

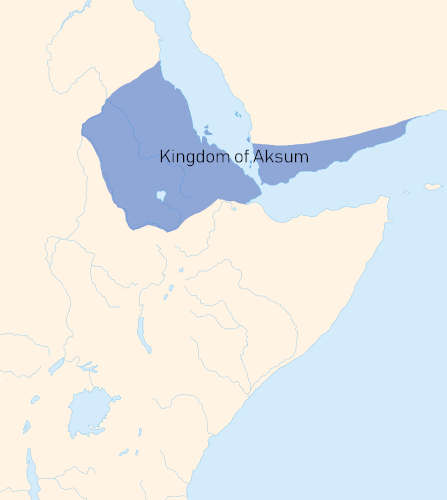

Archaeological evidence indicates that the kingdom emerged from a Proto-Axumite polity between circa 400 BC and 50 BC, although little details are known. At least by the 1st century AD, Axum had incorporated parts of the Red Sea coast, including the harbor city of Adulis, according to the Roman Periplus Maris Erythraei, a guide for merchants plying their trade on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean written around that time. Although the further rise of the early Axumite state is obscure, by the third century AD, it controlled much of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, while epigraphic sources indicate that the Axumites campaigned in all wind directions: from Egypt to the north, to Djibouti/northern Somalia to the east, the Ethiopian interior to the south, and the Nile valley to the west. They even temporarily expanded into southern Arabia, a region the kingdom shared religious, cultural and linguistic ties with.

Unfortunately, our knowledge of Axumite political history is deplorably lacunose: aside from some epigraphic material, scant literary sources and archaeological remains, the coins (to which we shall return below) are the most important sources for studying the political, economic and cultural developments of the kingdom. At the head of the Axumite state was the king (‘negus’ in Ge’ez), who, as far as we know, wielded semi-absolute, sacral power, and was worshipped as a son of the war deity, Mahrem, in pre-Christian times. Kingship was generally passed from father to son, though not necessarily based on primogeniture.

The Kingdom of Axum at its greatest extent in the 6th century. Image: Aldan-2 via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0.

As mentioned, Axum’s expansion towards the Red Sea included the conquest or incorporation of the port city of Adulis, located near modern-day Zula in Eritrea, a major gain that only accelerated the integration of the kingdom into a wide spanning and lucrative trade network running from the Atlantic Ocean to the Andaman Sea and beyond. An impression of the goods Axum might have supplied to foreign merchants, and what the Axumites would have wanted in return, is offered by the aforementioned Periplus Maris Erythraei. According to this indispensable 1st century source, the Axumites exported ivory, both of elephants and rhinoceroses, and tortoise shell, while they imported a variety of goods including textiles, glass, metal objects, unworked brass (which they supposedly cut up to use as small change) and Roman money for foreigners residing in Adulis. The Axumites were not passive recipients in this process, however: graffiti in Ge’ez found in a cave on the Yemenite island of Socotra, located some 230 km east of the Horn of Africa, show that the Axumites themselves also sailed abroad, although whether on their own ships or as passengers on foreign merchant vessels we do not know.

Christianity

With trade came foreign ideas, including a new religion. Previously, the Axumites had been polytheists, worshipping both their own deities and some imported from southern Arabia, but in the 4th century, Christianity was introduced in the country. Supposedly, the Axumites seized a Roman ship, slaying all aboard but two young, Christian boys, Frumentius and Aedasius, who were brought up to serve at the court, the former as treasurer, the latter as cupbearer. Legendary as this tale most likely is – it is reminiscent of so many ancient stories about stranded foreigners conveying knowledge – it reportedly occurred during the reign of Ousanas I (circa 325-345). However, it was his successor, Ezanas (circa 345-380), who eventually converted to Christianity and accepted the installation of Frumentius as Axum’s first bishop under the auspices of the Patriarchate of Alexandria. Over the following centuries, the new faith spread throughout the country, in part due to the influx of persecuted Roman Christians who did not follow official Church doctrine. To this day, Christianity endures in Ethiopia, though the country’s geographical removal from both Rome, Constantinople, and, after the rise of Islam, Alexandria, has caused the Ethiopian Church to retain many idiosyncratic elements, some perhaps even relics of its pre-Christian past.

Involved in Arabia’s Affairs

Though we are in the dark about many of Axum’s political developments after Ezanas, under Kaleb (circa 510-530s), the kingdom again entered the international stage when it invaded southern Arabia with Byzantine approval to stop the persecution of Christians at the hands of the Jewish Himyarite king, Yusuf. The campaign was initially successful, and an Axumite viceroy was installed, but a revolt soon broke out, possibly supported by Ethiopian troops stationed in Himyar, and Kaleb was ultimately unable to restore order, although he was later canonized as a saint for his efforts. It was not the last time Axum would be involved in Arabia’s affairs, however. According to Muslim tradition, the earliest followers of the prophet Muhammed were famously encouraged to seek refuge in Axum to escape persecution in Mecca (the so-called First Hijra), where they were welcomed warmly.

Downfall in the 6th Century

Internally, Axum appears to have declined over the course of the 6th century, perhaps in part due to the Plague of Justinian, which likely spread from Ethiopia to Egypt and the Mediterranean, and a potential sack of Adulis by a Sasanian expedition in the 570s (see lot 334). The deathblow to the Axumite kingdom came from the double calamity of the Sasanian conquest of Egypt under Khosrau II in 618 and the Arab conquest of Egypt starting in 639, exacerbated by the collapse of the Gupta Empire in India during the 6th century. All these events would have disrupted the Red Sea trade, the lifeblood of the kingdom, and soil degradation around the capital coupled with poor Nile inundations made a difficult situation untenable in the end. Axum was abandoned as the kingdom’s capital in the middle of the 7th century, and Ethiopia became more and more isolated as it lost access to the sea. The kingdom lived on until the 10th century, until it was conquered by the Ethiopian queen Gudit, who also sacked the former capital. The latter was not completely destroyed, however, and still exists as a smallish city today, its monuments silent witnesses to the splendour it once possessed.

Coins in Axum

Aside from the physical monuments which survive in Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Yemen, such as stelae, monasteries, and churches, one of the most enduring legacies of Axum is its coinage. Coin production likely began at the close of the 3rd century AD, during the reign of Endybis (circa 300-310). From the onset, the Axumites opted for a trimetallic system, consciously based on the Roman currency of the time, i.e., the aurei, argentei and nummi introduced by Diocletian in his sweeping coin reform in 294 AD, which would have been familiar through the Red Sea trade. To facilitate exchangeability, the early Axumite gold coins were struck at the weight of half an aureus, i.e., a gold quinarius of about 2.7 grams, although the weights of the other two metals were not as deliberately fixed to the Roman system, no doubt because of their smaller role in international trade during this period. That the coinage was intended for foreign exchange is also implied by the use of Greek legends, which survived on the gold coins down to the very last issues. While this may seem surprising, the Periplus Maris Erythraei notes that the Axumite king in the 1st century AD was well-versed in Greek, and there is no reason to assume this could not have been the case for Endybis and a certain segment of Axumite society. Reflecting the importance of trade with Graeco-Roman merchants, the Axumite gold coins also followed the later introduction of the Roman solidus (which came into broad use circa 324 AD) with a parallel weight reduction, so that they circulated at the weight of half a solidus, or a full semissis, of circa 2.25 grams.

Despite the clear parallels between the Axumite and Roman coinage, the former did not slavishly copy the foreign prototypes. For instance, one striking feature of Axum’s coinage is the common occurrence of partially gilding silver and bronze coins, attested as early as Endybis’ successor, Aphilas (circa 310-325). This was achieved by applying a mixture of gold and mercury with a fine brush or with a small, tapered rod to the coin, which was then heated, causing the mercury to evaporate. The success of this method is evidenced by the fact that many Axumite coins still retain partial or full gilding today. The primary reason for this process, which certainly took some effort, was no doubt to increase the value of the coin in question, but it also served to highlight certain iconographic elements, such as particular religious symbols or the king himself. In the latter case, the golden background may have appeared to grant the king an almost literal “golden aura”.

Iconography

As for the iconography, here too the Axumites developed their own particular style. Unlike with Roman coinage, which traditionally showed the imperial portraits on the obverse, Endybis placed his on both the obverse and the reverse of his coins. He is shown wearing a sacred head cloth, although from his successor, Aphilas, onwards, the gold coins would almost invariably show the king with a decorated tiara on the obverse, and with the sacred head cloth on the reverse. Other common attributes include a spear on the obverse (although this attribute severely degenerated under later kings), and a peculiar object, which is usually interpreted as a laurel or olive branch, a whip, or a fly-whisk, on the reverse. Flanking the king’s bust were two ears of barley, probably a fertility symbol. While this pattern was ubiquitous on the gold coinage – there are very few remarkable exceptions to this standardized depiction, such as lot 337, a unique chrysos of Gersem showing a frontal bust of the king on the obverse with a Byzantine-style crown – more iconographical experimentation is found on the silver and bronze coins. For instance, Aphilas produced an interesting issue of bronze coins showing a frontal bust wearing a head cloth on the obverse (lot 278), while Wazeba played with the convention by showing a tiaraed bust on both sides of an extremely rare issue of silver coins (lot 290).

Pre-Christian and Christian Issues

Unsurprisingly, the spread of Christianity had a great impact on the Axumite coinage. On the pre-Christian issues, we often find a pellet in crescent above the king’s bust. The moon had a religious connotation in practically all ancient cultures, while the pellet likely refers to either the Morning or the Evening Star. From the time of Ezanas (circa 345-380) onwards, these symbols would mostly be replaced with a Christian cross, which also appeared more regularly as the central design element on the reverse of the bronze coinage. The silver coins went one step further in the 6th century, depicting a shrine containing a cross or a schematized Eucharist scene (see lot 323).

Legends

Equally exciting are the coins’ legends. As noted earlier, the early Axumite coins carried Greek legends, identifying the king, his royal title (“ΒΑCΙΛЄYC ΑΞωΜΙΤωΝ”, which translates as “King of the Axumites”, later mostly changed to an abbreviated version of “ΒΑCΙΛЄYC XωΡΑC ΑΒΑCCINωN”, meaning “King of the Land of the Abyssinians”), and a curious element consisting of the word bisi, followed by various appellations (a nomen gentilicium meaning as much as “Man of …”). Though heavily debated, these may have been matrilineal clan names, and perhaps were also connected to particular groups within the Axumite army. In addition to Greek, Ge’ez was employed on the Axumite coinage, written in the Fidal alphabet. Ge’ez, still used as a liturgical language in the Ethiopian Church today, is a Semitic language closely related to Sabaean, from which it derived its alphabet. Especially from the reign of Kaleb (circa 510-530s) onwards, Ge’ez was in standard use on the silver and bronze coinage (although it was introduced on some coins as early as the reign of Wazeba circa 340, see lot 289). Again, Christianity had a clear impact on the coin legends. First, we have the appearance of several kings with biblical names, such as Kaleb, Joel or Israel, names clearly derived from the Old Testament and reflecting the more Aramaic form of Christianity that was practiced in Ethiopia. Moreover, the legends saw the employment of explicit and intriguing Christian messages such as “ΘЄΟΥ ЄΥΧΑΡΙCTIA” (“Benevolence for God” in Greek; see, for instance, lot 313), or the very impressive “bzzmmwwʼbʼbmmssqqll” (“In this (sign), you will conquer, through the Cross” in Ge’ez; see lot 303).

The Twilight of the Axumite Empire

The power struggle between the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires in the late 6th and early 7th centuries culminated in the dramatic capture of Byzantium’s eastern provinces and Egypt by Khosrau II (590-628) in the 610s and 620s, effectively cutting Axum off from their erstwhile political, economic, and religious partners to the north. The Sasanian Empire expanded into South Arabia as well, practically at Axum’s doorstep, and conflict between the two major powers is hinted at by burn layers found during excavations in Adulis, which likely fell victim to a Sasanian raid sometime earlier in the 570s. At the other end of the Red Sea-Indian Ocean trade, the Gupta Empire in India had splintered in the 6th century, putting further economic pressure on Axum. While the Byzantines briefly recovered their territories under Heraclius, the rise of Islam soon led to their permanent loss to the emerging Caliphate, resulting in the isolation of Axum from Mediterranean Christianity.

Like other peoples living at the periphery of world empires before and after them, the Axumites, under the political, cultural, and economic influence of their more powerful neighbors, had formed a cohesive realm of their own over time. Local kings emerged, undoubtedly spearheading, as with most pre-modern states, a powerful elite that demanded the distribution of wealth and prestige. The lucrative participation in international trade also brought along dependencies, however, a vulnerability not unknown to a modern world still recovering from the shock of a global pandemic. With the fall of the Gupta and Sasanian Empires, the emergence of the Islamic Caliphate, and Byzantium’s desperate fight for survival, centuries of relative ‘international’ stability came to an end. Within this changing world, Axum had to reinvent itself, and it became more focused on its African hinterland as it lost its access to the sea. All this would have sharply reduced the need for coin production, which had always been oriented towards international trade. Posthumous coinage may have continued to be struck for a while after Hethasas/Hataza’s reign, and the coins of earlier kings likely also continued to circulate, but sometime during the middle of the 7th century, when Axum was abandoned as the kingdom’s capital, coin production was effectively halted. The kingdom itself endured until the 10th century on a minor scale, when it was conquered by the Ethiopian queen Gudit, who also appears to have plundered the former capital, but native coins would not be minted again in Ethiopia for more than a thousand years. All this only adds to the fascination of this rich coinage, struck in one of the least-known corners of the ancient world, a true testament to Axum’s bygone power and prosperity.

Collecting Axumite Coins

Because of the large gaps in the historical source material, the exact arrangement of the Axumite kings and their reigns is often uncertain, and it is to be expected that future discoveries will further adjust our understanding of Axumite political and numismatic history. As for the names of the denominations, the usage of Greek terms such as chrysos, argyros, lepton, and so on is common. This is, of course, a compromise: the Axumites themselves most certainly used different terms, now lost to us, but by attaching a name to the denominations, we can more easily show the metrological relations between the different issues than if we would employ the generic term “Unit”. Finally, in the cases where the king’s bust is shown on both sides of the coin, the habit is to describe the tiaraed side as the obverse, irrespective of the legends or technical aspects. For those coins with a royal bust on only one side, this too is treated as the obverse.

The End of Axumite Coinage and the Coffman Collection

Alas, as did the fortunes of the kingdom, so too fared the coinage. When Axum was abandoned as the capital around the mid-7th century, it appears that coin production also halted. Ethiopia returned to a barter economy, and it was only in the 18th century that indigenous Ethiopian coins would be struck once again! All the more remarkable then is the series of coins from the collection of Dr. Stephan Coffman offered at the Leu Auction 14. The selection showcases the highlights of Axumite numismatic history, from its very inception up to the final issues, and displays a delightful mixture of aesthetic appeal, great historical interest, exceeding rarity (with many pieces only known from a handful of examples or even unique), and excellent provenance. The latter is reflected by the many coins hailing from the collection of Francesco Vaccaro (1903-1990), an Italian numismatist who was active in Eritrea from the 1940s till 1978, and who built his own collection of Axumite coins, many of which were published in a catalogue in 1967. As mentioned in his biography, the scientific importance of Dr. Coffman’s collection is underlined by the fact that most of his coins are cited in Hahn & Keck’s latest catalogue of Axumite coins. Dr. Coffman’s coins are not only the best examples of a rich and fascinating coinage, the only one struck in Sub-Saharan Africa in Antiquity, but they also lie at the nexus of the political, cultural, religious and economic history of Axum. As such, Dr. Coffman’s coins are an indispensable historical source for a kingdom for which so few other sources remain.

Axumite Bibliography

- Anzani: Numismatica Axumita, in: Revista Italiana Numismatica 39 (1926), pp. 5-110.

- Anzani: Numismatica e Storia d‘Etiopia, in: Revista Italiana Numismatica 41-42 (1928/9), pp. 5-69.

- de Blois: Clan-Names in Ancient Ethiopia, in: Die Welt des Orients 15 (1984), pp. 123-125.

- Hahn: Die Münzprägung des Axumitischen Reiches, in: Litterae Numismaticae Vindobonensis 2 (1983), pp. 113-180.

- Hahn: Numismatische Reisenotizen aus Äthiopien, in: Mitteilungsblatt des Instituts für Numismatik der Universität Wien 16 (1998), pp. 9-14

- Hahn & V. West: Sylloge of Aksumite Coins in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Oxford 2016.

- Hahn & R. Keck: Münzgeschichte der AkßumitenKönige in der Spätantike. Vienna 2020.

- Munro-Hay: Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh 1991.

- Munro-Hay & B. Juel-Jensen: Aksumite Coinage. London 1995.

- Munro-Hay: Catalogue of the Aksumite Coins in the British Museum. London 1999.

- Phaidra: online database at https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/

- Vaccaro: Le Monete di Aksum. Mantua 1967.

This article was first published in auction catalog 14 of Leu Numismatik. Lot numbers in the text refer to this catalog.