Bulgaria, Prince Ferdinand I and the Railroad

On 3 March of every year, Bulgaria celebrates its national day. On this very day, Bulgarians commemorate the fact that their territory became an independent principality after the April Uprising of 1876 and the Treaty of Berlin in the same year.

Content

We can only truly understand the historical background of the medal offered by Künker when we keep in mind that the Bulgarian government planned to forge closer ties with Western and Central Europe as its territory had long been neglected by the Ottoman central government. They wanted Bulgaria to become an economically strong nation so that it would be in a position to maintain its independence. And in all these considerations, two aspects played a decisive role:

- How could they successfully gain the trust of investors?

- And how could the money of these investors be used to remedy the country’s infrastructural deficits as quickly as possible?

The Prince: A Glorified Representative of the Bulgarian Nation

We must bear in mind that the time of absolutist monarchs had long been over and done with. The young nation of Bulgaria adopted an extremely progressive constitution and crowned a monarch that would exert as little influence on the government as possible. At the same time, the monarch should be well respected by the European nobility and Western economic leaders so that he would be in a position to promote Bulgarian government bonds. Moreover, a potential candidate should be to the liking of all major European powers. He would have the task of balancing France and Russia on one side and the German and Habsburg Empire on the other. All of them – just like Britain – pursued their own agenda on the Balkans.

Alexander I of Battenberg failed to accomplish this task. After his resignation, Bulgaria appointed Ferdinand I of Saxe-Coburg-Koháry as his successor in 1887. Ferdinand was the youngest son of an Austrian general from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and, on his father’s side, related to almost all European ruling dynasties. His mother Clémentine of Orléans was the daughter of the French Citizen King Louis Philippe and did not only provide him with great personal wealth but also with excellent connections to the French business world.

During the first years of his reign, Ferdinand I repeatedly visited the rich industrial countries of Europe to promote the interests of Bulgaria. To this intent, he was highly imaginative when it came to getting in touch with the financial aristocracy. A good example for this is how he established a personal connection to Friedrich Alfred Krupp in 1893. Krupp supplied weapons, railroad engines and carriages – these goods were of great interest to a country that was investing in infrastructure while building up a modern army at the same time. To secure an invitation by Friedrich Alfred Krupp, Ferdinand sent him a high Bulgarian order. Of course, he was rewarded with a letter thanking him for it and an enclosed invitation to the Hügel villa. Of course, Ferdinand happily obliged. He travelled there along with the prospective Bulgarian Prime Minister to discuss business in peace and quiet.

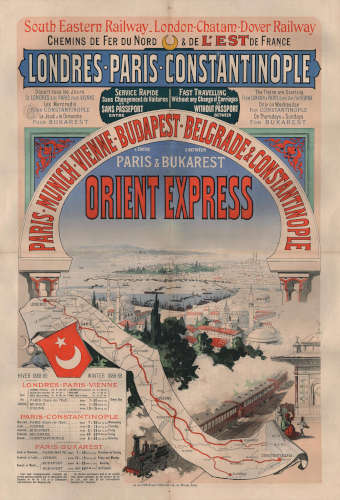

Whenever it became difficult to secure funding, Ferdinand himself actively took part in the negotiations. He was supported in his efforts by Georg von Siemens. The latter was one of the founding directors of Deutsche Bank, which particularly liked to invest in railroad projects. Not only did it fund the Baghdad railroad, it also financed the Northern Pacific Railway and the section from Yambol to Burgas in Bulgaria, an event that was celebrated by this medal.

By the way, Ferdinand I was also rewarded for his services as prince. He received 300,000 francs a year and an additional 90,000 francs from Eastern Rumelia. This sum was more or less what the kings of Serbia and Greece received for their activities. After his wedding (and probably also because he had proven to be highly successful in convincing foreign investors), the Bulgarian government increased his salary to 1.3m francs a year.

In 1902, Ferdinand I travelled to Russia in his personal and luxurious railroad carriage. Bulgarian State Archive 3K / / 476 / 16.

Industrialization and the Railroad System

Under the Ottomans, Bulgaria had been an agricultural country whose wealth depended on the weather. In case of a poor harvest, the national treasury immediately suffered a blow. Therefore, the government was forced to lower the salaries of state officials by 15 to 30% following the two crop failures in 1898/9. To avoid any discussions, Ferdinand immediately waived 50% of his civil list.

Given the difficult financial situation, the government had no option but to finance the construction of the infrastructure by means of public bonds. The main focus was on the railroad system. It was of crucial importance when it came to transporting goods into and out of Bulgaria.

A detail goes to show how quickly and effectively Bulgaria promoted its railroad system: when Ferdinand I traveled to Bulgaria in 1887 to be crowned in Sofia, he still used horse-drawn carriages, ships and horses – in the constant danger of being mugged. When his young wife came to Sofia in 1893, she already travelled by railroad.

This immense achievement can also be demonstrated in numbers: When Ferdinand took office, the Bulgarian railroad system comprised 541.5 kilometers. When he resigned, 1,683 kilometers had been added. With the help of Ferdinand, the Bulgarian government issued 328.6 million leva of public bonds to finance its construction. The Bulgarian railroad system with all of its fixtures served as a collateral to investors.

The Orient Express

It would have been impossible to raise this money without Ferdinand’s efforts. This became clear when the last part of the legendary Orient Express was built. On 1 November 1887, the Serbians completed their last piece of the line. So, Bulgaria was the only interruption of the railroad from Western Europe to Istanbul.

The problem: when Ferdinand assumed office, Bulgaria was not creditworthy. European investors were hesitant to finance a project of which they thought that it was impossible to complete within a reasonable timeframe. This is where the mother of Ferdinand I came in. She offered a million francs from her private assets as credit. Of course, the entire corporate world eagerly waited to see whether Bulgaria would be able to redeem the debt.

And, indeed, the country repaid Ferdinand’s mother. The line was built at record speed. As early as on 19 June 1888, on the occasion of the first anniversary of Ferdinand’s accession to the throne, he was able to open the railroad for domestic carriages. On 9 July of the same year, a train of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits carried out a test drive. And as of 12 August 1888, the Orient Express regularly traveled back and forth between Paris and Istanbul. The Bulgarian national railroad received its share of the ticket sales and was able to repay the credit, including high interest.

This broke the ice, and when Bulgaria issued public bonds in 1889, they were oversubscribed sixfold. At the time, Bulgaria offered the highest interest rates in Europe.

The Railroad Line from Yambol to Burgas

The railroad line from Yambol to Burgas had not been financed with this capital but with the help of Deutsche Bank and the Wiener Bankverein, a major Austrian bank. The act stipulating the construction of this railroad line was adopted on 21 January 1889. It was to connect the fertile soils of western Bulgaria with the important Port of Burgas in the Black Sea. By means of the railroad, Bulgaria hoped to gain better access to the European market in order to sell its grain.

On 1 May 1889, the first cut of the spade took place. The 110-km railroad was built at record speed – in a little over a year – by Bulgarian sappers and engineers and with the help of the local workforce. Therefore, it was solemnly opened as early as on 14 May 1890.

The plan of the Bulgarian government bore fruit. Just a few years later, it became clear that the port of Burgas had to be expanded in order to transport even more tobacco and grain across the Black Sea. In 1898, the Bulgarian national assembly decided to reconstruct the port for 20 million leva.

A Medal “For the Construction of the Railroad Line from Yambol to Burgas”

But let us get back to the railroad line from Yambol to Burgas. On the occasion of its completion, the Bulgarian Ministry of Finance issued with Ukas No. 76 of 14 May 1890 (published in the state gazette No. 110 of 25 May 1890) the medal “for the construction of the railroad line from Yambol to Burgas”.

It was created in three sizes: with a diameter of 90mm, not wearable, in gold; with a diameter of 50 mm, not wearable, in plated bronze, silver and bronze; and with a diameter of 30 mm, wearable, in silver and bronze. The designs were created by Joseph Christian Christlbauer (1827–1897); the dies were engraved by Johann Schwerdtner in Vienna, where the medals were struck.

Large gold medal on the construction of the railway line between Yambol and Burgas from May 14, 1890. To 110 ducats 1890, by Johann Schwerdtner in Vienna, diameter 89.6 mm, 382.8 g. From Künker auction 395 (2023), lot 323. Of the greatest rarity. Splendid specimen. Estimate: 50,000 EUR.

According to Pavlov (in PA p. 248) and Petrov (in PE5 p. 176 f.), initially only a single medal with a diameter of 90mm (de facto 89.6mm) was minted and given to Prince Ferdinand I in a Bordeaux, octagonal velvet case. The piece was probably made of 986/000 gold and equated to the value of 110 ducats with a weight of 383.2g. The obverse depicted the portrait of Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria looking to the right with the circumscription ФЕРДИНАНД IИЙ КНЯЗЬ НА БЪЛГАРЯ [Ferdinand I Prince of Bulgaria], below the neck was the engraver’s signature “J.SCHWERDTNER”, and on the reverse a steam locomotive passing over a bridge, probably over the Tundzha river [Тунджа] near Yambol with the circumscription ЯМБОЛЪ – БУРГАСЪ 14 МАЙ 1890 [Yambol – Burgas 14 May 1890]. The design of the steam locomotive was probably inspired by the type of which an engine is on display as exhibit No. 148 at Bulgaria’s National Transport Museum in Ruse [Pyce] in the north of the country.

After the death of Ferdinand I on 10 September 1948, the medal was inherited by his youngest daughter Nadeja Princess of Bulgaria (30 January 1899 – 15 February 1958), who was married to Albrecht Eugen Duke of Württemberg (8 January 1895 – 24 June 1954); and after her death it was passed on to their heirs.

According to Pavlov (in PA p. 248) and Petrov (in PE5 p. 176 f.), a second large gold medal of the same diameter was given to Ferdinand’s mother Clémentine on the Prince’s request, as a symbol of appreciation for her great idealistic and financial support in the development of the Bulgarian railroad. However, this specimen has been lost.

Künker takes pride in being able to offer this great rarity from the estate of Ferdinand I at its auction sale 395, which testifies to the great personal commitment and the enthusiasm of Ferdinand I when it came to expanding the railroad system across his entire country.

Caricature from 1908, picking up the railroad obsession of Ferdinand: Ferdinand sits enthroned on a locomotive. The engine is drawn by the Prime Minister, who pulls Ferdinand at his nose – a common theme to indicate that he is being led up the garden path. Ivan Geshov, another Bulgarian politician, is pushing the locomotive while the personification of the treaty of Berlin was thrown under the carriage. In the background, high-spirited Bulgarians cheer at this journey to Constantinople. The caricature refers to the fact that Bulgaria asserted its independence in 1908 and elevated Ferdinand I to the position of tsar.

The Railroad Tsar

Such enthusiasm seems a little out of character for a ruler, and was picked up by many anecdotes that were spread about Ferdinand I and his love for locomotives. We do not know how much truth there is to these stories, but some of them are simply too good not to be told.

We certainly can assume that the intelligent prince, who was obsessed with machines, knew a lot about the matter. He probably decided himself which locomotives were acquired when his mother funded the engines for the line between Vakarel and Zaribrod.

In general, Ferdinand repeatedly visited production plants on his trips and is said to have astonished the engineers with his in-depth knowledge. Of course, Ferdinand often travelled by train, but he apparently was also able to drive a steam locomotive himself – a skill that was rather rare in the 19th century. Especially among the upper class.

Did Ferdinand really know how to drive a locomotive? Well, what is most remarkable is that people thought he was. A prince willing to get his hands dirty: there is hardly a better image that a constitutional monarch could spread in order to convince his subjects of his efforts to promote Bulgarian interests. So perhaps there is some truth to the accounts that state that Ferdinand I liked to tease the welcome committees at train stations. They obviously gathered where his private carriage was scheduled to stop. But instead of elegantly waving from his carriage as expected, the prince is said to have jumped off the locomotive in a train smock, his face smeared with soot and his hands dirty.

The Western media obviously made fun of it. They reported that Ferdinand I allegedly asked the train driver of the Orient Express to let him take control of the driver’s cab. Ferdinand is said to have enjoyed to drive fast and brake hard. So, the passengers complained to the organizer. Rumor has it that the Compagnie Internationale des Wagon-Lits then instructed their staff not to allow the prince to get onto the locomotive anymore.

Behind these jokes was probably a lot of envy of a prince that managed to make a country at the then end of the world known throughout Europe within a few years, while working together with Europe’s corporate elite. Otto von Bismarck, at any rate, held Ferdinand in high esteem: “Prince Ferdinand is certainly more capable than his reputation in humorous magazines and that of most other princes.”

This opinion was probably shared by most Bulgarian train drivers. A delegation is said to have honored Ferdinand I with a train driver diploma, in Honoris Causae so to speak. Moreover, it was said that Ferdinand always made sure to personally thank the railroad staff at the end of a train journey and give them gifts and cigars.

Increasing Exports and a Flourishing Trade

It is difficult to say whether these stories are true or fabricated. What we do know for sure is that the railroad system significantly contributed to the development of Bulgaria. Via the Orient Express railroad lines, machines purchased in Western and Central Europe came to the country – duty-free and at a reduced cargo price.

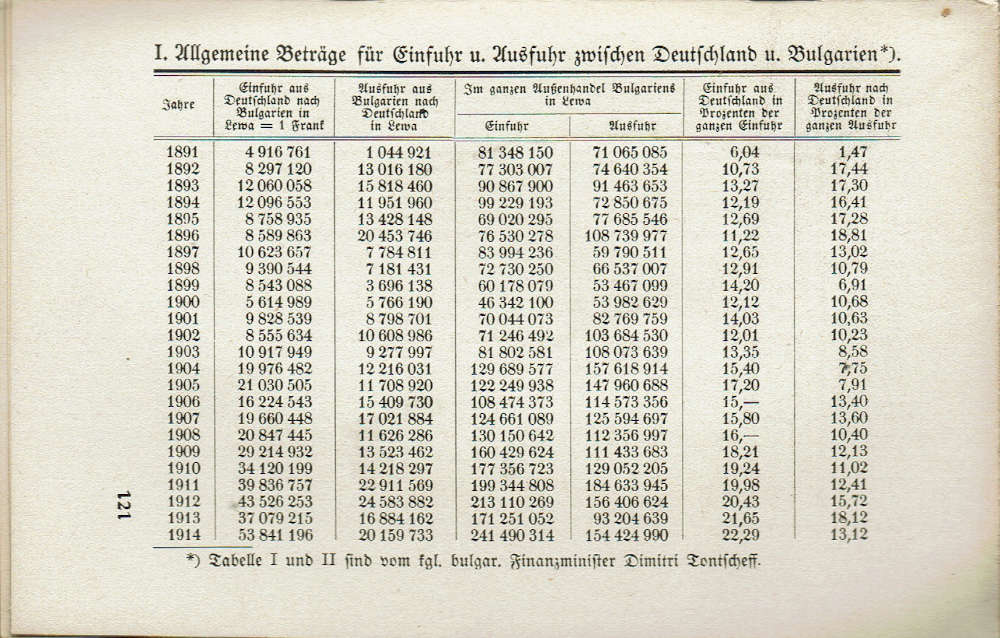

In turn, the line from Yambol to Burgas transported the harvest of western Bulgaria to the Black Sea in order to be shipped to Europe. The export of grain and grain products to Germany rose from a volume of about 7,900 leva in 1891 to 11,380,000 leva in 1912.

The Prussians of the Balkans

Ferdinand I succeeded in improving Bulgaria’s image throughout Western Europe. Otto von Bismarck liked to refer to Bulgarians as the “Prussians of the Balkans” – a major compliment by his standards. And as early as in 1890, he highly praised the Bulgarian nation: “Among the Balkans and according to all one can experience and observe, the Bulgarians seem to carry a nation-building and nation-preserving element. And they are a capable, industrious and economical people who devote themselves to slow and steady progress. A people that honors, expands and defends itself, and I like it…”

The gold medal commemorating the railroad line from Yambol to Burgas from the estate of Ferdinand I is a wonderful memory of a great ruler and a people that managed to become an important part of Europe within a few decades.