The Heidelberg Tun and Early Modern Winemaking

There are often attempts to translate sums of money from the past into modern currency. Those who try to do so, however, have no understanding of the early modern economy, because it functioned very differently to today. Money only played a secondary role.

Content

Take, for example, taxes and the salaries paid to civil servants. What we are able to do so easily today with a few bank transfers used to be a huge logistical feat until the complete monetisation of the German economy in the 19th century.

The work in the vineyard. Monthly painting for September by Hans Wertinger, produced around 1516-1525. Note the representative of the authorities, dressed in lordly attire and supervising the work in the winepress. Kunstmuseum Basel Inv. G. 2013.1. Photo: KW.

How Was Winemaking Taxed in the Palatinate?

The prince-elector of the Palatinate, for example, derived a large part of his income from winemaking. He received a very specific percentage of the profits from every vineyard in his territory. How much did he take? Well, we can’t say exactly, because almost every individual winegrower had their very own, historically established agreement. These agreements varied depending on geographical location and rights of ownership. The land’s legal status and the people cultivating it were also important factors. It was therefore incredibly difficult for the princes of the early modern period to collect taxes. They needed extremely precise documents telling them who owed them what.

However, that didn’t mean the authorities didn’t try. The electoral Chamber of Accounts was responsible for collecting the excise duty on wine. It upheld specific local tax offices, intended to ensure that the requirements of the territorial rules were met. After all, since the Middle Ages, winemaking had been a centralised controlled process: when should the vines be pruned, fertilised, grafted? Which tools should be used? This was all decided by the authorities.

Official staff of a Tyrolean saltner, who was employed to supervise the vineyards before the harvest. Tiroler Volkskunstmuseum / Innsbruck. Photo: KW.

Four weeks before the harvest, only official supervisors were allowed in the vineyard. And they weren’t just scaring birds away. Their most important task was to prevent the winegrowers from siphoning off some of the harvest before it was taxed. Because after the harvest, there was no escaping the tax. These officials supervised the harvest, as well as the transportation of the grapes from the vineyard to the winepress. This also belonged to the territorial lord, whose officials would collect their share of the wine there and then.

The wine was then stored at the local tax office. And then, before the wine was transported to Heidelberg, all the local officials were given some as part of their salary.

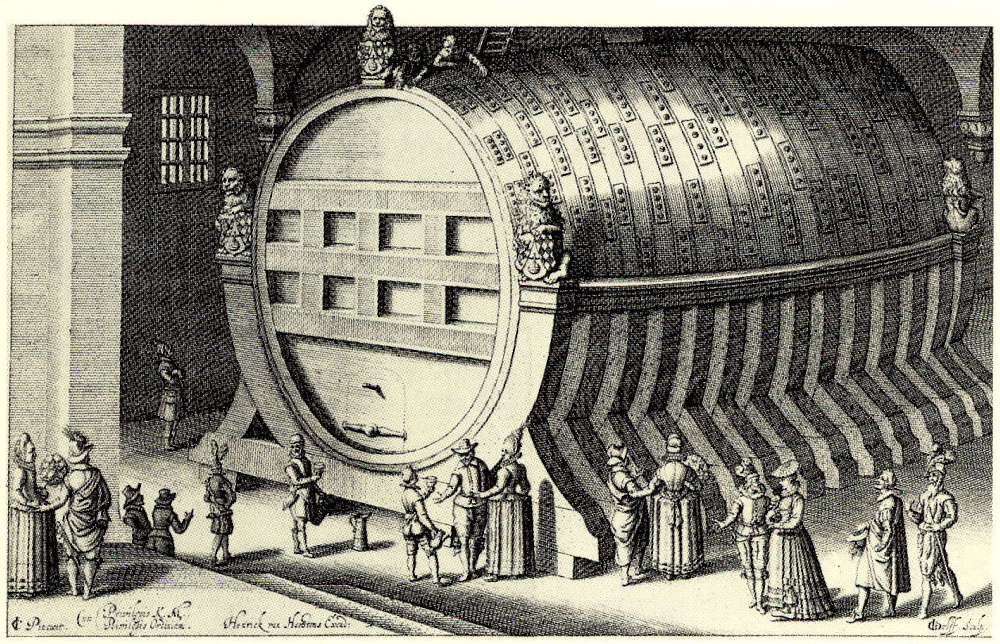

The first great Heidelberg Tun, depicted in an illustration by the Reformed engraver Willem Jacobszoon from the Dutch city of Delft.

The First Heidelberg Tun

After that, the wine – if requested by the territorial lord – was transported to the residence. In 1592, Frederick IV of the Palatinate had a large barrel built to store this wine.

This wouldn’t be very remarkable in and of itself. After all, there were grand barrels like this one in residences across the Holy Roman Empire, which were used to store the wine collected as tax revenue. However, the Heidelberg Tun was slightly larger than these other barrels; and the Palatinate was a pioneer of Calvinism; and so the Calvinist theologian Anton Praetorius turned the giant barrel into a symbol of the success of this belief system, which was highly controversial in the empire. After all, the Calvinists were not included in the Peace of Augsburg, which officially ended the religious struggle between Catholics and Protestants.

In 1594, Praetorius published a Latin polemic all about the Heidelberg Tun. It was an international success that made the Tun famous among Calvinists throughout Europe.

Now, in the 1600s, it was customary for those aspiring to a career in the civil service to embark on a “grand tour”, that is, a tour of the courts of the most important rulers. The purpose of this trip was to build up a network of contacts. The places that somebody visited on their grand tour depended on which religious group they belonged to. Now, the prince-elector of the Palatinate played a critical role as a leading figure for the Calvinists and the Protestants. They flocked to Heidelberg en masse, marvelling at the Heidelberg Tun that Praetorius had made famous.

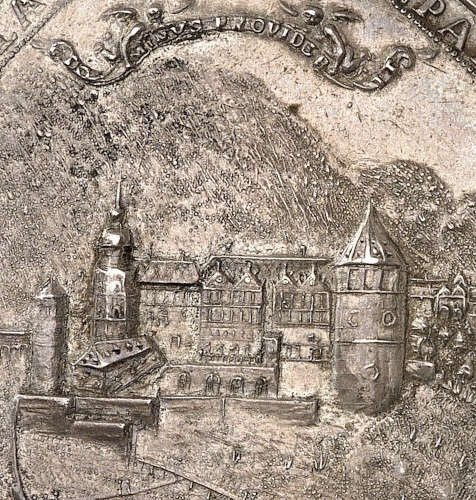

Octagonal silver medal commemorating the second Heidelberg Tun by J. Linck, 1667. Very rare. Beautiful patina. Extremely fine. Estimate: 4,000 euros. From auction 394 (28 and 29 September 2023), Lot 5071.

The Second Heidelberg Tun

And then came the Thirty Years’ War, which cost Frederick V, the “Winter King” and Prince-Elector of the Palatinate, his rule. It was not until 1649 that his son was able to regain possession of the land, which had been completely destroyed by the war. There was a great deal of restoration work to be done. In order to pay for it, the prince-elector radically reduced his spending, and ensured that taxes were collected in full. Gradually, prosperity returned to the Palatinate.

This was also reflected in the income generated from winemaking. Soon, the old barrels in the castle cellar were no longer sufficient to store this tax revenue, especially since the first Heidelberg barrel had been leaking for decades. For that reason, in 1659, the Court of Auditors suggested replacing the old giant barrel with a new one. A cost estimate was calculated, after which the Chamber of Accounts determined that this barrel must hold at least 160 “fuder” (cartloads) of wine and cost a maximum of 750 reichstaler.

A wine barrel is moved to the wine cellar. Painting from the 16th century. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Photo: KW.

In 1663, the giant barrel was clearly expected to be completed soon, because the old barrel was demolished. In spring 1664, the new barrel was brought to the wine cellar and gauged. For four days, in the presence of a representative of the Chamber of Accounts, the two mayors of Heidelberg and two officially appointed “barrel-gaugers”, the head servant poured one measure of water after another into the cask to test its capacity. The total capacity came to 204 fuder, 3 ohm, 4 viertel – which probably equates to about 195,000 litres.

If we estimate the average price of wine at 30 rechnungsgulden for a fuder, as was typical at the time, the second Heidelberg Tun could store about 6,120 rechnungsgulden worth of wine. In the final accounts, the costs of the tun came to 1,732 rechnungsgulden, 57 kreuzer and 6 heller. That wasn’t much at all. In 1610, the prince-elector at the time had requested a cost estimate for the repair of the first tun, which amounted to more than 3,500 rechnungsgulden.

In autumn 1664, the second Heidelberg Tun was filled with wine for the first time. The carters had actually planned to drive their teams into the large hall and fill the tun from there. But Charles Louis – understandably – forbade this approach. Much to the annoyance of the workers, they were required by personal order of the prince-elector to unload every single barrel in the courtyard, and roll it through the great hall and over a plank bridge to the trap door where they could empty it into the Heidelberg Tun.

In the same year as this first filling, the Heidelberg goldsmith and die-cutter Nikolaus Linck made a medal. Whether he did so on the orders of the ruling house or on his own initiative, we do not know. In any case, this medal must have been an extremely popular souvenir among the young gentlemen who visited Heidelberg and its great tun on their Grand Tours, because by 1667, Nikolaus Linck had already produced another medal with the same motif, but octagonal. This rare piece will be sold by Künker in auction 394, held on 29 September 2023. The obverse of this medal depicts Heidelberg Castle.

The Heidelberg Tun as a Tourist Attraction

The obverse of this medal depicts Heidelberg Castle, the reverse depicts the tun itself. The inscription translates loosely as follows: “Here you see an image of the Palatinate Tun, there is none more large or more beautiful.” As if to underscore this point, the artist captures numerous details. We see a small Bacchus enthroned on top of the tun, waving two goblets. Around him, Pan figures are spread out among intertwining grapevines. The coat of arms is in the centre, held by two lions, with the electoral hat depicted above and the initials of Charles Louis below.

The medal also clearly depicts the balustrade on the top of the giant barrel.

The “third” Heidelberg Tun. Drawing by Peter Friedrich de Walpergen, 1743. Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg.

The purpose of this balustrade is demonstrated in an illustration of the “third” Heidelberg Tun from 1743, which was probably also once produced as a souvenir for the many tourists visiting Heidelberg.

From the second Heidelberg Tun onwards, all the barrels were accessible from the top so that the prince-elector could host parties and take tourists up there. A splendid experience that could well be compared to visiting the head of America’s Statue of Liberty today: the true majesty of a structure can only be appreciated up close.

The “Third” and Fourth Heidelberg Tun

In any case, the Heidelberg Tun became a hit among the public and a symbol of power. And it didn’t matter that it couldn’t be stopped from leaking. In 1680, the second Heidelberg Tun was filled for the last time. However, the prince-elector of the Palatinate was all too happy to use it for his court festivities, so between 1724 and 1728, he had it completely renovated – which is why the “third” Heidelberg Tun looked strikingly similar to the second.

But it was still leaky, so a new tun was commissioned in 1750. And this is the one that still attracts curious tourists from all over the world today.

Incidentally, the Heidelberg Tun holds neither the record for the oldest giant wine barrel in the world (that one is in Halberstadt), nor that for the largest, which you will find in Dürkheim. Its status as a tourist attraction is exclusively due to Praetorius’ publication in 1594. That is so often the case with tourist attractions: most of the time, we’ve forgotten why we actually want to see them.