Career goal: Saint – Bernward of Hildesheim

The eldest son inherits the land, the second eldest assumes a church office, and so it was in the case of Bernward who was to be anointed Bishop of Hildesheim in 993. He was of the best Saxon nobility. His uncle Folkmar served as chancellor at the court of Emperor Otto II. Of course, he took care of his sister’s son who was born in 960 and turned out to be very promising very soon. Folkmar made sure that from his earliest youth on Bernward was educated in the cathedral school of Hildesheim, at that time a kind of elite school where the future officials of the Saxon empire learned what they had to know to administer the empire.

Map of the various parts of the Duchy of Saxony around 1.000. Source: NordNordWest / Wikipedia. CC-BY-SA-3.0-EN.

You may remember that the Liudolfings dynasty, better known today as the Ottonians, which had ruled since 916, had its political focus in the Duchy of Saxony. At that time, this included Eastphalia and thus Hildesheim, the bishop’s seat dating back to the Carolingians. There was not only a magnificent cathedral, but also the even more important cathedral school at which Bernward received his education.

Bernward is said not only to have been interested in the seven liberal arts, which were, so to speak, compulsory subjects. Already at that time, he was passionate about craftsmanship, which was highly unusual for a nobleman!

In 977, Uncle Folkmar introduced his 17-year-old nephew to the imperial court. The emperor employed him as one of his secretaries, a respected and important position at a time when the written document was a statutory right. Bernward probably came into close contact with the imperial family, for when Theophanu, Otto II’s widow, was looking for a tutor for her seven-year-old son, who would later become Emperor Otto III, she chose him.

Was Bernward anointed bishop of the important town of Hildesheim in 993 as a reward for his services? Or did Otto’s grandmother Adelheid recognize the wealth of Bernward’s talents? In any case, the clergyman himself informs us in his deed of foundation for St. Michael’s that he had already firmly resolved to become a saint on the occasion of his ordination as bishop.

He planned to realize this goal not as a martyr or ascetic, but as an architect of heavenly splendour on earth. This included not only the construction of the monastery of St. Michael, which is listed today as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but also the many liturgical artefacts that Bernward commissioned – and of course all of which he marked with his name.

The best known are probably the Bernward Doors and the Bernward Candleholder, both of which are Romanesque masterpieces that can be seen in Hildesheim Cathedral today. Bernward probably got the inspiration for this on his travels to Rome (Santa Sabina for the door; the imperial columns for the Bernward Candleholder), to St. Denis and Tours (for the architecture of St. Michael’s).

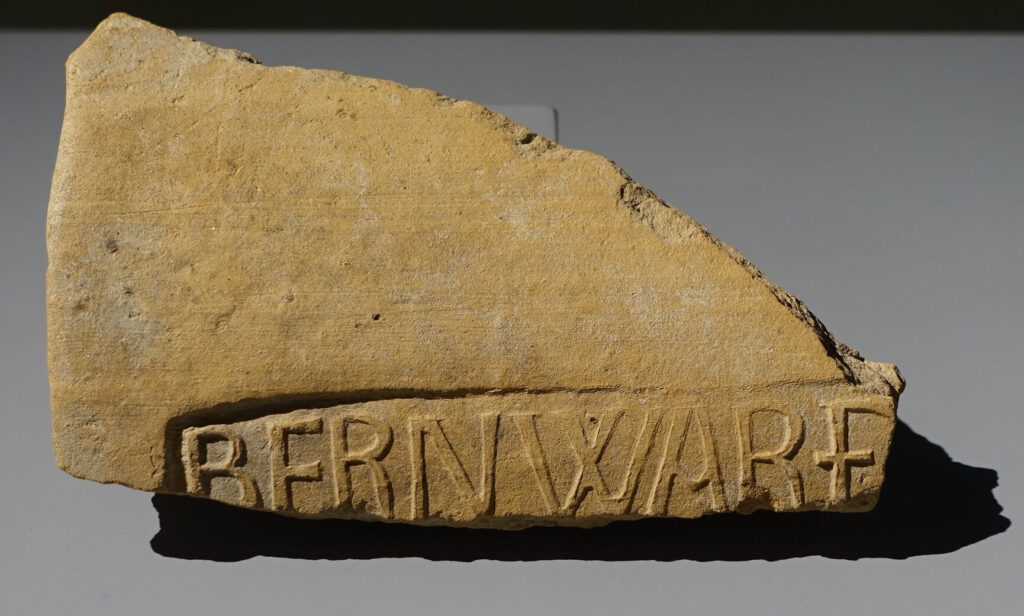

Bernward’s foundations were preferably not made of perishable material, but of stone or bronze, so that Bernward could be sure that people would remember him for many generations to come. Bernward used the media of his time systematically – none of his episcopal contemporaries had a comparable amount of inscriptions. For instance, Bernward had his name stamped on thousands of tiles with which he had the roof of the cathedral newly covered.

And since coins are of course also wonderfully suited to pass on one’s own name to posterity, Bernward carried out an extensive coinage in which we can read his name and title on the obverse of the pfennigs, and the name of his diocese of Hildesheim on the reverse.

Do these coins show the minting authority himself on the obverse? There is a possibility. Bernward was innovative enough to understand the impact of a portrait, and proud enough to consider himself worthy to be depicted on a coin.

When Bernward died in 1022, he let himself be buried centrally in the crypt of his St. Michael’s Church, confident that this would soon be a place of pilgrimage for him as a future saint of the Catholic Church. On his tombstone he had the following text written: “Part of humanity was I, Bernward, now I lie pressed in this dreadful coffin, worthless and, look, as ashes. Woe to me that I did not lead my so high office well! Gracious peace be upon my soul, and you, sing your Amen.”

Of course, Bernward was convinced that he had actually performed his office very well. But humility was good for a future saint. Too bad that his successor Godehard did not play this game. Godehard was not from high nobility. He came from a small family of servants and had received his education in Niederaltaich, at that time a centre of Cluniac reform. There, the proud bishops of old noble descent were not popular at all. One who writes his own name on a coin! Disgusting! On Godehard’s coinages of course, his own name is not mentioned at all. Only the veiled Mother of God can be seen on the obverse of his coins. No, Godehard could not discern anything sacred in Bernward’s actions. On the contrary: The disgust he felt for his predecessor can be inferred from the fact that he tried to relocate the convent of Bernward’s St. Michael’s Church. But he was unsuccessful.

To cut a long story short, the future belonged to Cluny and his reformist clergyman. Not Bernward, but Godehard, who died in 1038, was canonized in 1131. His cult spread throughout Central Europe. We know 439 places where he was worshipped. This brought many pilgrims to Hildesheim, and of course they also visited the monks of St. Michael’s. For the Benedictines, it was a wonderful opportunity to still receive the late canonization of their founder (and thus profitable relics). So they reported to Rome what at that time was a precondition for canonization: blind people who could see again, paralyzed people who could walk again, liberated prisoners, rescued shipwrecked people, the usual. And indeed, the Provincial Synod could not avoid allowing the Abbot of St. Michael’s to erect an altar above Bernward’s remains. But nothing more.

In the end, it was the construction of the monastery of St. Michael’s that secured Bernward his place in the Catholic Heaven. A papal legate came back from Scandinavia and was stuck in Hildesheim in the summer of 1192. The monks of St. Michael’s granted him lodgings – and he expressed his gratitude by promoting the canonization of Bernward in Rome. The abbot of St. Michael’s, who had travelled to Rome with him, brought the mandate of Celestine III with the canonization back to Hildesheim in 1193.

However, Bernward never became as popular as Godehard. Save for a few exceptions, his cult remained limited to the diocese of Hildesheim, from where we certainly know coins featuring his portrait. Anyway, the oldest seal of the city of Hildesheim did not show the architect bishop Bernward, but the reform bishop Godehard.