Gate Tokens: Relics of Nuremberg’s History

What Is a Gate Token?

The primary purpose of a gate token is to enable its owner to pass any gate of a city wall, at any time, and – above all – without being subject to inspection. What seems commonplace to us couldn’t be taken for granted when the Nuremberg gate tokens that are on offer at Künker were created in the 17th century. After all, the city wall strictly separated the inside from the outside at that time – and there were two reasons for this.

The first was a matter of defense. City walls protected the city from being conquered. That’s why city gates had to be carefully patrolled to prevent disguised enemies from entering the city. At night the gates were closed. Anyone who didn’t pass them before the evening bell rang had to spend the night outside the walls.

But that wasn’t the only purpose of a city wall. It also served as a customs barrier. Those who came from outside to sell goods at the Nuremberg market had to pay customs at the city gate. After all, this was the easiest place to check how many head of cattle the Hungarian herds comprised that streamed across Nuremberg’s Fleischbrücke (“Meat Bridge”) into the city’s famous slaughterhouses.

Those who possessed a gate token weren’t subject to this control, which is why these specimens are also referred to as “toll gate tokens”. However, only three people of Nuremberg could hold such a carte blanche at once.

Who Got Such a Gate Token?

In an essay published in the “Jahrbuch für Numismatik und Geldgeschichte” in 1971, Herbert J. Erlanger, the well-known collector of Nuremberg issues, was able to prove that gate tokens did not serve practical but representative purposes. Together with the city keys, the members of the Nuremberg triumvirate were entrusted with these tokens. The most important people watching over Nuremberg’s finances were the “Supreme Losunger”, the “Second Losunger” and the “Third Supreme Captain”. They were at the top of the inner Privy Council and headed the government of the city of Nuremberg.

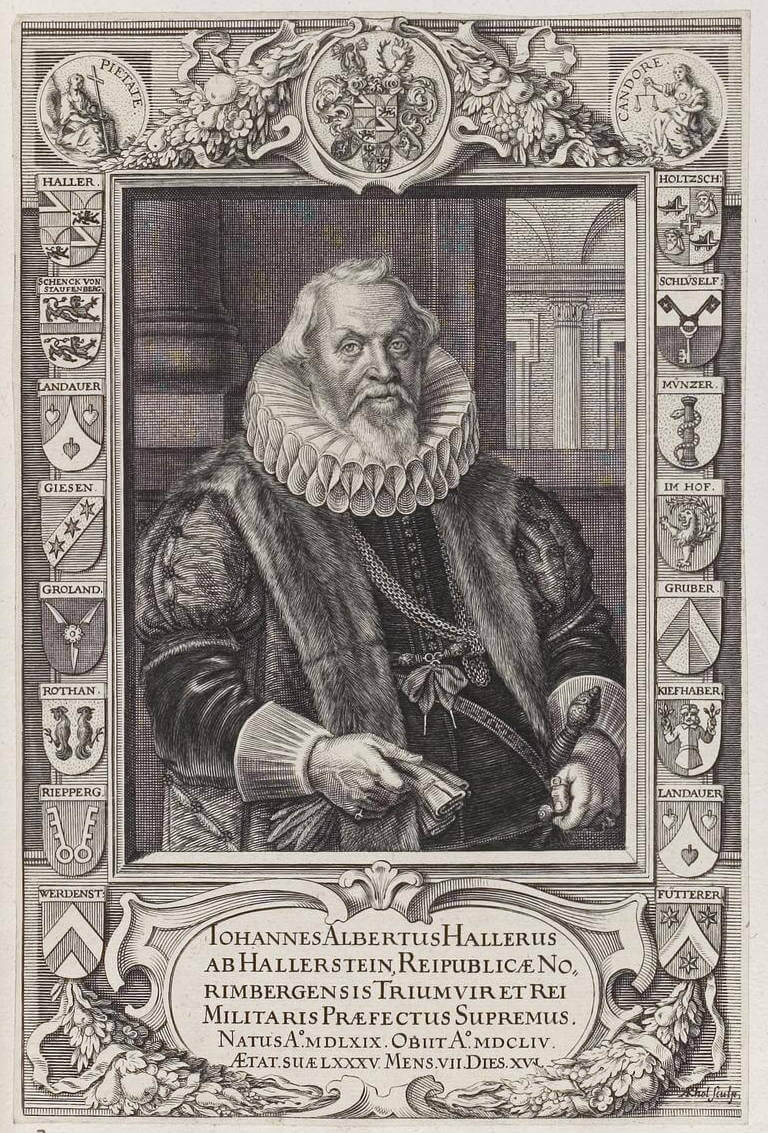

It’s quite revealing that the twofold function of the city wall is also reflected by the titles of the triumvirs, who possessed one gate token each. After all, the Losung office administered the city’s finances and was thus in charge of collecting taxes. And the title “Supreme Captain” is much less ambiguous in its Latin version: Rei Militaris Praefectus Supremus – Supreme Head of all military affairs.

So it was a very select group of Nuremberg citizens who had a gate token. Did the triumvirs show their tokens frequently? That’s very unlikely. After the 30 Years’ War, Nuremberg was said to have about 25,000 inhabitants. The gatekeepers must have known the city’s three leading politicians in person.

Thus, every single gate token is unique and was hand-made for one of the leading members of the city’s government. The pieces are made of silver, were engraved and the engraving highlighted by means of a black paste. On the obverse, they show one of Nuremberg’s three coats of arms. Around it, there is a phrase taken from Psalm 126, whose translation reads as follows: if the Lord does not guard the city, he who guards it guards in vain. The date corresponds to the year in which the official first received the gate token, i.e. in which he was appointed triumvir.

The reverse mentions the name of the triumvir who held the token, without his title. In our case, the token was owned by Johann Albrecht Haller von Hallerstein. We know his portrait. We also know that he lived from 1569 to 1654 and held the office of Supreme Captain of Nuremberg since 1653.

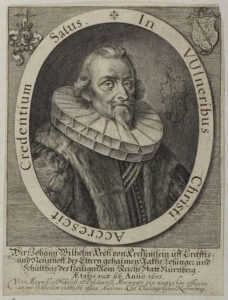

We know even more about Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein, who succeeded Johann Albrecht Haller von Hallerstein after his death in the Nuremberg triumvirate. For we do not only have his portrait but also his funeral oration.

It tells us that Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein was born on 11 May 1589 into an important Nuremberg family. His father had been “Pfennigmeister”, a kind of finance minister of the Holy Roman Empire, during the Turkish war. He fell in 1596 at Pressburg fighting the Turkish troops, leaving young 7-year-old Hans fatherless. So rich relatives took care of the child.

1723 silver medal with the depiction of the University of Altdorf. Extremely fine +. Estimate: 5,000 euros. From Künker auction 375 (29 September 2022), No. 2041.

They sent the boy – as was customary at the time – to university in Altdorf sometime after his 12th birthday. At the age of 19, Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein completed his Grand Tour, another must-do event of the high society. It not so much served the purpose of education, but helped the young man to learn foreign languages and build up a personal network with the international upper class. As was custom in Protestant circles, he did not go to Italy but to France, England, Holland and to the Kingdom of Bohemia, to pay his respects to the emperor.

At the age of 26, Johann Wilhelm Kreß married a girl named Susanna, with whom he had nine children, only three of which survived him – again, this wasn’t unusual in the 17th century either.

Nuremberg. 1619 silver medal with the depiction of the Nuremberg town hall. Minor traces of mounting. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 750 euros. From Künker auction 375 (29 September 2022), No. 2024.

As was natural for a member of the Nuremberg leadership elite, Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein inexorably climbed up the career ladder. At this point, we will do without mentioning all the offices, honors and administrative posts he gradually accumulated. His funeral preacher, the then very well-known pastor Martin Limburger, listed them meticulously.

However, we do not want to leave out a personal detail: In his spare time, Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein studied genealogy, a very widespread and respected pastime back then. He wrote several manuscripts on the subject, but not a single one of them was printed.

Moreover, Martin Limburg praised the deceased’s piety to the skies. This could well be considered a common topic of funeral sermons. However, the personal motto that the engraver Andreas Kohl added to the portrait of Johann Wilhelm also testifies to his devotion to the faith. It’s translation reads: salvation grows in faith in the wounds of Christ.

What we have to keep in mind is the fact that Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein was among the leading Nuremberg politicians of his time. He played a crucial role in steering Nuremberg through the turmoil of the 30 Years’ War and was one of the men who, after the Peace of Westphalia had been concluded, persuaded the warring parties in the imperial city of Nuremberg to implement, bit by bit, the goals set out in the treaty. The negotiations following the Peace of Westphalia were referred to as the “Nuremberg executive congress”, and were at least as important for the pacification of Germany as the Peace of Westphalia itself.

Nuremberg. Silver gate token, created in 1654 for Johann Wilhelm Kreß von Kressenstein. Extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker auction 375 (29 September 2022), No. 2060.

Without the diplomatic skill of Nuremberg patricians, the mercenary troops of the various warring parties would have continued to trouble the Holy Roman Empire for much longer. Johann Wilhlem Kreß must have distinguished himself in these negotiations. For he was elected “Second Losunger” on 21 October 1654. On this occasion, his silver gate token, which is now offered at Künker, was made. On 7 July 1655, he was elected “Supreme Losunger”, a position that was connected to the office of “Reichsschultheiß”, i.e. the emperor’s representative in Nuremberg. His gate token wasn’t altered on this occasion.

Johann Wilhelm Kreß died at the age of 68, probably due to pneumonia. He left his widow, two sons, one daughter, twelve grandchildren and his silver gate token, a true relic in the historical sense of the word.

There isn’t a way in which numismatics could bring us even closer to a policy-maker of the early modern era, is there?

The gate marks as well as further pieces of the Franconian regional collection can be found in the Künker Auction 375.