The hunting prince

The Baroque prince: Instantly we visualize a grand castle with an impressive state bed at a central location, a carefully arranged garden setting with expensive banquets and even more expensive ballets staged, intrigues, hoop skirts, not to mention the beehive wigs that make their wearer appear to be even taller. And all the time we forget that the whole Baroque court community was keen to leave all that ceremonial behind and go for a ride through nature as a hunter and a huntress.

Lot 3157. Habsburgs. Ferdinand II, 1619-1637. Triple jagdtaler 1626, Breslau. Rv. The emperor with plume hat riding l., behind him hunters and two hunting dogs at the gates of Vienna. Extremely rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 20,000 euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

When this triple jagdtaler featuring the portrait of Ferdinand II was minted, the small hunting lodge that Louis XIII had built in Versailles was only three years old. All over Europe, the princes were pursuing the battue to take their mind off things. On their own or with a small entourage, they engaged in a privilege that distinguished the nobility from the common people.

For the large game was a prerogative of the high nobility. The lower clergy and the bourgeoisie were allowed to shoot a hare or a roebuck, but the wild boar and especially the deer was for the sovereign alone.

Lot 3286. Stolberg. Johann Martin, 1638-1669. 2 ducats 1646, Rottleberode. Av. Deer standing l. at a column. Extremely rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 7,500,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

From very early on, the stag thus became one of the animals which were frequently depicted on coats of arms, for instance on this coin of Johann Martin von Stolberg-Stolberg. The counts of Stolberg already showed a stag in their coat of arms prior to 1429.

Lot 3166. Austrian Estates. County of Sporck. Franz Anton, 1679-1738. Gold medal 1723 of 1 1/2 ducats. Av. St. Hubert kneeling in front of a deer, flanked by a horse and two hunting dogs. Rv. Eagle, a hunting horn around its neck as well as the medal for St. Hubert. Extremely rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

And so the stag became something like the quintessential hunting pleasure, as we can see on this medal that was commissioned by Franz Anton, Imperial Count of Sporck. It features St. Hubert, patron of both the hunt and the huntsmen. St. Hubert is said to have converted as he saw a cross standing between the antlers of a stag he was just chasing.

Franz Anton von Sporck was a keen hunter himself, who had brought the parforce hunt to Bohemia on his return from the court of the Sun King. For himself and his descendants he paid Emperor Leopold I 120,000 gulden for the right to kill eighteen pieces of game – half stags, half wild boars – in the imperial hunting district near Lissa every year. He admitted his ruler friends, who accompanied him on the hunt, in his Order of St. Hubert. Its members belonged to the hunting elite of Europe: Emperor Charles VI, King Frederick August II of Poland and King Frederick William I of Prussia were decorated with Franz Anton von Sporck’s Order of St. Hubert.

Lot 3183. Hesse-Darmstadt. Ludwig VIII. Jagdtaler 1751, Darmstadt. Av. Stag chased by hunting dogs. Rv. the handler of the hunting pack galloping. Very rare. Almost extremely fine. Estimate: 7,500,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

Parforce hunting was therefore not only a princely pleasure, but also a status symbol that brought ruin on more than one ruler. One of these was Ludwig VIII von Hesse-Darmstadt, who entered history not only as the hunting landgrave; he also initiated the most extensive coinage featuring hunting motifs.

Lot 3169. Hesse-Darmstadt. Ludwig VIII, 1739-1768. 2 ducats no year (around 1750), Darmstadt. Av. Parforce hunt for a twelve-pointer. Rv. The twelve-pointer being caught by three hunting dogs. Very rare. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 10,000,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

Ludwig, too, was enthusiastic about parforce hunting, as we see on this double ducat: The stag is being hunted by the dog pack that is pushed by the whipper-ins with their whips.

Lot 3178. Hesse-Darmstadt. Ludwig VIII, 1739-1768. Hirschtaler no date (around 1750), Darmstadt. Av. Deer in front of Kranichstein Castle. Rv. Stretched deer hide (= deer skin) with allusive saying regarding cuckolded husbands. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 4,000,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

We do not see the prince himself on these coins. He rides further back, at the head of the courtly hunting party, through a staged landscape. To him, the act of hunting is not only sport and pleasure, but also a Baroque artistic synthesis that appeals to as many senses as possible. The elaborate hunting music that accompanied the event was of course an indispensable element in this context. The prince becomes active only when the deer is run down and surrenders. Then it is the privilege of the ruler to kill it…

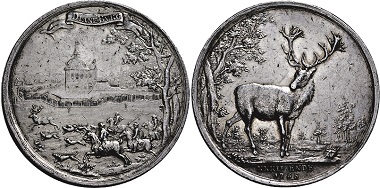

Lot 3184. Hesse-Darmstadt. Ludwig VIII, 1739-1768. Double jagdtaler 1765, Darmstadt. Av. Parforce hunt in front of Dianaburg Castle. Rv. Standing thirty-two-pointer. Rare. Very fine. Estimate: 2,000,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

…or grant it amnesty, as happened to the royal thirty-two-pointer, who went down in hunting history as the “Battenberg stag”. The animal was captured alive on November 11, 1763. A specifically designed car then transported it to a park near Darmstadt, roughly 200 km away, where it was shot in 1769 a year after Ludwig VIII had passed away.

Ludwig von Württemberg after the hunt at Bebenhausen. Oil painting, Württembergisches Landesmuseum. Photo: KW.

In addition to parforce hunting, the hunt with the help of fences was extremely popular in Baroque times. It posed less stringent demands on the royal hunter’s fitness.

Prior to the hunt proper, assistants marked out a small, manageable area with wooden fences and covers made of cloth. The game was driven there. The court ceremonial laid down in every detail who was actually allowed to shoot it – usually, that was the sole privilege of the prince, providing he did not have a visiting dignitary of equal rank from abroad.

Detail of the painting above. Photo: KW.

At the scene of the kill, in the presence of the noble hunting party, the killed animals were gralloched and disemboweled.

Detail of the painting above. Photo: KW.

The intestines were given to the dog pack.

Lot 3254. Saxony. Medal 1719 on the wedding of Electoral Prince Friedrich August with Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria. Av. Artemis as huntress with spear, quiver, and hunting dog. Rv. Water hunt in front of the Dresden cityscape. Very rare. Extremely fine to almost FDC. Estimate: 5,000,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

Such hunts were an integral part of virtually every major Baroque festivity, including the wedding between the Saxon successor to the throne, Friedrich August, and the daughter of Emperor Joseph I, which was celebrated in Dresden.

The festive event lasted seven days. Each day was devoted to a particular deity that inspired the relevant pleasure the court was enjoying. Diana’s day was dedicated to the hunt, more specifically to a special form of the courtly hunt that was particularly pricy: the water hunt.

The whole court community went on a lavishly equipped ship for such a water hunt. In Bavaria, a replica of the Venetian bucentaur had been built for this very purpose. An expensive purchase, but to August the Strong, money was probably no object, either. From aboard the safe vessel, the wedding company was now shooting at the stags and the wild boars, which were driven into the water by the beaters.

The hunt was a costly enterprise not only for the prince. It was a great burden for his subjects, for the game devastated the fields of the peasants. If a furious farmer killed such a pest, he was facing a fine, imprisonment and / or corporal punishment.

Adding to this was the socage. Individual farms were obliged to keep and train hunting dogs. Others had to produce the wooden elements for the hunt with fences, or serve as drivers, which was not completely free of danger, by the way. During the 1848/9 revolution it became clear to see how much people actually hated the princely hunt. Using axes and scythes, peasants attacked and plundered the forestry offices. They burnt down the lists of socage services stored there, and virtually organized their own battues to get rid of the loathed wild boars and deer.

The assembly meeting in St. Paul’s Church took account of this concern to the peasant population when it abolished the princely privilege and granted the landlords the right to hunt on their own grounds.

Lot 3164. Habsburgs. Franz Joseph I. Gold klippe 1898 on the hunt on the occasion of the 50th reigning anniversary. Unique. FDC. From the personal possession of Franz Joseph I. FDC. Estimate: 2,500,- euros. From Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 (September 21, 2017).

And so it was quite a political demonstration that the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I, who rose to power on December 2, 1848, initiated a large-scale revival of the hunt.

Hunting trophies of Emperor Franz Joseph I in his summer retreat in Bad Ischl. Photo: Ilya Kuzhekin. CC-BY 3.0.

And the vast amount of hunting trophies that astound the visitor of the imperial villa in Bad Ischl are by no means a mere curiosity, but a demonstration of the power and the conservative attitude of the ruler.

This is a far cry from modern, responsible hunting.

All coins and medals illustrated here form part of the Hirsch Nachf. sale 333 on September 21, 2017. They stem from the collection of a keen collector and huntsman. The relevant auction preview can be read on our German site, MünzenWoche.