Two Dukes in Pomerania

On January 31, 2013, the Pomerania collection of Friedrich Popken will be coming up for auction. Here, we present two coins from the collection that are as different as the men who had them minted.

Philip II (Pomerania-Stettin). 6 ducats, undated, Stettin. This unicum will be up for auction at Künker on January 31, 2013 with an estimate of 25,000 EUR.

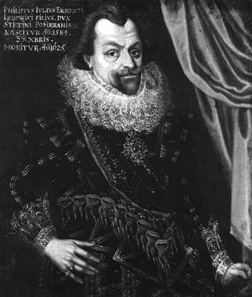

The sextuple ducat piece that Philip II had minted in Stettin sometime during his reign between 1606 und 1618 is a truly splendid stamping. The front depicts a dignified man with a mid-length beard. Although he wears a suit of armour, his facial features resemble those of a scholar. The inscription reads, in translation, ‘Philip II, by the grace of God, Duke of Pomerania.’ On the reverse, a slightly modified Pomeranian griffin is featured in the middle with a sword and book, and around it, the coats of arms of the principalities in Pomerania. Between the coats of arms reads the motto of Philip II: CHRISTO ET REI PVBLICAE – ‘for God and the state.’

‘For God and science’ would actually have been more appropriate, since Philip II was not an active statesman. Born on July 29, 1573, he was, in fact, never earmarked for a significant role within the state. For a sizeable apanage, his father had foregone all claims to power, and, as such, Philip was able to grow up without any pressure and indulge his passion for religion and art. By the age of 18 he had already written: ‘It’s a pleasure to collect good, select books, portraits from a master’s hand and ancient coins of all kinds. From these I learn how to improve myself and, at the same time, how to be of benefit to the general good.’

Philip had the great fortune to make numerous grand tours and also had the opportunity to study at the University of Rostock. The year 1603, however, spelled the end of his pleasurable, relaxed lifestyle – through the vagaries of succession law, Philip’s father became ruler of Pomerania-Stettin and, naturally, expected his son to support him in the government. In 1606, his father died and Philip II assumed responsibility. He married and dedicated himself to the administration and management of his empire. His best-known measure is the 1616 introduction of the rural regulations in Pomerania-Stettin, which established a legal basis for serfdom. For a devout Christian like Philip, this measure offered a sensible means of securing God-given world order.

Philipp II of Pomerania. Wikipedia.

The melancholy, gout-ridden prince became even more renowned, however, for his collections and his extensive correspondence with important scientists and politicians, including James I, King of England and son of Mary Stuart. In his letters, Philip spoke of theological and moral issues. He also told his friends of the new publications being released by his printing plant in Barth, and also of new purchases for his collections. New pieces were constantly being added to these collections, thanks largely in part to Philip Hainhofer of Augsburg, who acted as Philip II’s broker in the art trade. From 1610 on, the art dealer and his customer would correspond every week, and this continued right up until Philip II’s death. We know that Hainhofer procured a coin collection for Philip, among many other artistic treasures. The most famous testimony of the collaboration between the two, however, is the so-called ‘Pommersche Kunstschrank’ (Pomeranian Curiosity Cabinet), which was made by Augsburg craftsmen for 20,000 gulden and was tragically destroyed in a hail of bombs during the Second World War. When Philip died on February 3, 1618, this outstanding amount had still not been paid, something that wasn’t unusual for his time. Philip was succeeded by his brother, who did everything he could to raise the necessary funds and resources to help ready Pomerania for the anticipated hostilities.

Philip Julius (Pomerania-Wolgast). Double imperial thaler, 1609, Franzburg. This coin is another unicum from the Friedrich Popken Collection and will be up for auction on January 31, 2013 with an estimate of 20,000 EUR.

The presentation of Philip Julius on this double thaler from 1609 is in marked contrast to that of his cousin, Philip II. On the front, Philip Julius’ hair falls in a wild head of curls, and he sports a rather modern-looking goatee, both very much in keeping with the trend of the time. He also wears a suit of armour, but here the armour is almost completely obscured by the stiff lace collar and an honours chain. The inscription reads ‘Philip Julius, by the grace of God, Duke of Stettin and Pomerania.’ The reverse also depicts the Pomeranian coat of arms, but it is elegantly framed by two rugged men wearing elaborately adorned jousting helmets. Between them, another jousting helmet decorated with peacock feathers crowns the shield. The motto that Philip chose for himself is interesting and testifies to just how misunderstood this prince felt: One must bear misfortune by bearing; patience will bring forth fame and victory.

Philip Julius. Wikipedia.

And yet, everything had started off so well. When his father, the Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast, died in 1592, the seven-year-old Philip Julius was the darling of the court. He was given the best possible upbringing for his time, and learned knightly discipline, riding, fencing and jousting. He must have been good at them too, since time and again we see evidence in the diaries kept during his grand tours of his having excelled in knightly games. But his intellectual side was also well attended to – in Oxford, he offered his perfectly worded thanks for the rector’s Latin speech; and in Geneva, he chatted with one of the most renowned theologians of the time, the Calvinist Theodor Beza.

The more serious side of life began for Philip Julius in 1604, the year he assumed power over Pomerania-Wolgast. He quickly found himself in financial straits, as he was all too eager to reproduce in Wolgast the magnificent holdings of courts he had witnessed on his trips. By 1613, his royal court is said to have consisted of 254 people, all of who had to be both housed and paid. It’s little wonder that the states were none too pleased with this extravagant lifestyle and showed themselves unwilling to finance it.

Perhaps it was this lack of support that led Philip Julius to attempt to capitalize on civil unrest in Greifswald and Stralsund for his own financial purposes. Even though he was unsuccessful in bringing both cities fully under his control, the revenue from the conflict with Greifswald amounted to a one-off payment of 14,000 gulden. On top of this, a tax of 25,000 gulden was to be made in annual instalments of 2,200-2,300 gulden. Following a military intervention by the Duke, for which he was in fact sentenced for a breach of the peace by the Imperial High Court (without consequence, mind you), Stralsund declared its willingness to offset the full maintenance costs of the court and of the royal councils. Philip Julius is also to have received a one-off bonus payment in the amount of 35,000 gulden.

This still wasn’t enough to satisfy the demands of the pomp- and luxury-accustomed duke. But the payments did, at least, prevent Philip Julius from mortgaging the island of Rügen to Denmark for 150,000 thalers. Even in Pomerania-Wolgast, no one was investing in defense, despite the fact that the war was imminent. Philip Julius died at the age of 40 on February 6, 1625, and so did not have to live to witness the continued occupation of his land first by imperial, then by Swedish troops. The Thirty Years’ War devastated the Duchy. It became a battlefield that was to be divided between Sweden and Brandenburg in the Treaty of Westphalia.

If you want to have a look at these coins in the Künker sale, click here.

And here you will find all three upcoming sales of Künker.