What Can Be Seen on Euro Coins: The Brandenburg Gate Part 1

Actually, German euro coins seem to be rather unimaginative when compared to those of other countries. We’ve already seen oak leaves on countless occasions and the German federal eagle isn’t much of an original symbol either. The Brandenburg Gate was the only new addition made to the design programme of circulation coins at the introduction of the Euro. This innovation is a numismatic acknowledgement of the symbolic importance of a building that already became the architectural epitome of the German nation and its unity before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Anyway, let’s start at the beginning, in 1788.

In 1788, the old Brandenburg Gate (here depicted in an engraving of 1764) was no longer splendid enough for the metropolis of Berlin. Therefore, Frederick William II commissioned the design of a monumental building.

Building a New Gate

1788, that’s the year in which the old Brandenburg Gate was demolished. It was nothing but a simple passage, which interrupted the fortification belt and had the purpose of creating a connection to the outside while facilitating the control of customs duties on goods at the same time. However, such a small, inconspicuous gate no longer met the standards of the time. Berlin had become a capital of European importance and its days as simple fortress were gone. Something more monumental and impressive was needed as an entrance to the city. Thrifty “old Fritz”, as they called him, was dead, and the new king Frederick William II was a man who was rather averse to the military and inclined to subtle entertainment – a characteristic that wasn’t compatible with the Prussian tradition at all. Thus, he commissioned the construction of numerous buildings. For his new capital, he needed splendid palaces and squares, wide streets and a gate through which one could enter the city during festive parades in a suitable way.

Therefore, the decision was made to build a triumphal arch. And it didn’t take long to find an occasion for building it. In 1788, the Prussian army restored control over a few revolutionaries in the Netherlands by its mere presence. It had been a weekend war, a military parade of no actual importance, and it had almost been forgotten when the plans for the overwhelming triumphal gate that was to celebrate this tiny victory were made.

An Architect Called Langhans

Carl Gotthard Langhans, born on 15 December 1732 in Landeshut / Silesia, was responsible for the design and the construction of the Brandenburg Gate. Langhans hadn’t studied at one of the art academies, which came into fashion during the 18th century. He was a self-taught man, who had educated himself on architecture after studying law and mathematics. The young man had patrons who paid for his educational trips to Italy and France, from where he returned with his sketchbooks full of designs and his head filled with the new ideas of classicism. However, much time passed before the architect had the opportunity to build a representative monumental building. Even though Langhans entered the service of Frederick the Great and designed buildings on behalf of the government, practical matters had to be tackled first: Silesia had been destroyed and needed to be rebuilt. Thus, Langhans designed provincial barracks and bridges, streets and canals, churches and houses.

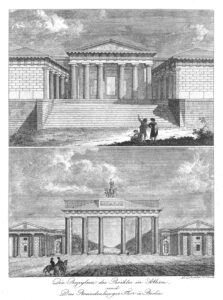

In an engraving, Johann Carl Richter (about 1795) compares the Propylaea of Athens and the Brandenburg Gate. As long as he was alive, architect Langhans was often criticised due to the similarity of the monuments.

He only made it to the capital quite late and thanks to a stroke of luck. After the death of Frederick II, Frederick William II travelled through the most important cities of his realm to be paid homage to. He also came to Breslau, where Langhans had designed the festive decorations. These decorations were so extraordinary that, in 1788, the newly crowned monarch made Langhans director of the Oberhofbauamt (Royal Office of Constructions) in Berlin. In this position, he was commissioned to re-design the Brandenburg Gate.

Langhans was given instructions: the gate he was to build should have as many “openings and possibilities to look through” as possible. In a memorandum he wrote to the king: “The location of the Brandenburg Gate is undoubtedly the most beautiful of the entire world. To make most of this and to include as many openings as possible in the gate, I took the gateway to Athens as a model for the new gate.” Thus, it was to be a classicist building. Berlin, which had already been called “Athens of the Spree river” for a long time, was to get its own Propylaea. The construction works, which started at the end of 1789 and thus in the same year in which the French Revolution was initiated by the Storming of the Bastille, cost a total of 110,902 talers.

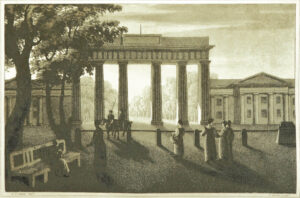

The Brandenburg Gate (here in a depiction of 1796) was considered by many contemporaries an unimaginative copy of the Athenian model.

Mockery and Ridicule for the Brandenburg Gate

You can totally argue about the artistic value of the Brandenburg Gate, and people did that in the past. Especially Johann Gottfried Schadow mocked his colleague, who wasn’t academically trained: “Was it distrust in his own ideas or convenience, anyway, he (Langhans, author’s note) liked to borrow. On his journeys he had filled his sketchbooks, and, to him, repeating acknowledged masterpieces seemed to be the safer option than new original buildings created by us.” Many of Schadow’s contemporaries were of the same opinion and considered the Brandenburg Gate a building that did not exactly spark much imagination. It was not until the turn of the 19th century that Langhans was treated more justly as a Berlin pioneer of classicism. In 1893, for instance, a literary critic wrote: “Even though it is an imitation of the Propylaea on the Acropolis of Athens, with which it has in common the general arrangement of a gate framed by two protruding wings, it (the Brandenburg Gate, author’s note) is not a mere imitation but an intellectually stimulating new creation of a remarkable monumental effect.”

The metopes also used the ancient model of an allegorical battle between culture and barbarism fought by mythical creatures, namely by Lapiths and Centaurs. Photo: Axel Mauruszat / CC BY-SA 4.0

Langhans set up a comprehensive iconographic programme for his building. The common theme wasn’t victory in war but victory as the bringer of peace. Thus, the Attica relief depicts the entry of the triumphing goddess of peace, the relief of the metopes were dedicated to the battle of the Lapiths against the Centaurs – an ancient parable symbolising the battle of culture against barbarism. At the passageways, observers saw the deeds of Heracles; in the 19th century, this was immediately understood as a parable for the prince, who accomplishes great deeds to the benefit of his subjects through his righteous government. The crowning glory of the iconographic programme and the actual crown of the Brandenburg Gate should be a Quadriga drawn by four horses and driven by a mixture between the goddess of victory and the goddess of peace. Schadow, of all people, who criticised the architect so unfavourably, was commissioned to design the Quadriga. A coppersmith from Potsdam was appointed to carry out the work. Despite several difficulties, the Quadriga was finished just in time, and yet, people were terrified when the work of art reached the capital: Victoria was naked, and that was something no Prussian citizen could bear to see. The goddess of victory had to be dressed quickly. A coat was forged for her, the legs were sawn off to attach the new garment and in the September of 1793 the Quadriga completed the new building.

A nightmare for Prussians: leading his troops, victorious Napoleon entered Berlin on 27 October 1806 through the Brandenburg Gate. Painting by Charles Meynier (1810).

When the Frenchmen left, they had taken the Quadriga to Paris. All that remained on the Brandenburg Gate was an iron rod, which had served as support for the work of art. (Engraving created before 1817).

An Exhibit in the Musée Napoléon

There she stood, Victoria, looking down from her dizzy location on people constantly coming and going. Back then, huge doors still had to be opened whenever a visitor wanted to pass the gate. The passageway in the middle was reserved for passers-by of princely blood.

However, unwelcome visitors soon arrived in Berlin. On 27 October 1806, Napoleon entered Berlin, which had been left in haste by Frederick William III and his wife, the famous Queen Louise of Prussia. The first person who passed the Brandenburg Gate in triumph was thus the “French upstart”, of all people. The uninvited visitors stayed there for two years. 60,000 Frenchmen had to be accommodated by 170,000 inhabitants of Berlin. And that disturbed the people of Berlin certainly more than the looting of Monsieur Dominique Vivant Denon, Directeur général des Arts, who had been commissioned by Napoleon to confiscate the most important works of art of each country in order to fill a huge “Musée Napoléon”. The Quadriga of the Brandenburg Gate was not among the pieces of art that Monsieur Denon “organised” in Berlin – and this certainly annoyed Mister Schadow – however, it was at least one of the trophies. Thus, despite vivid protests from all sides, Victoria was removed from the roof with the help of the same coppersmith that had made the casting and was taken to Paris. The only thing that remained on the gate was the iron rod that had previously served as support for the work of art.

In the second part you will read how the Quadriga returned and the Brandenburg Gate turned from an ugly duckling into the symbol of Germany.

The Brandenburg Gate was repeatedly featured on Germany’s recent numismatic issues, for example on the 10th silver Quadriga of the mint of Berlin.

In 2014, Germany issued a 10 euro commemorative coin in honour of the man who criticised Langhans, the creator of the Quadriga, Johann Gottfried Schadow.