Poets and their income: Walther von der Vogelweide

translated by Christina Schlögl

Walther von der Vogelweide can surely be deemed the most famous minstrel of the German Reich. And yet we do not know all that much about his life. The most valuable source are still his poems, impressive poems, which illustrate numerous details of his life’s journey.

Walther von der Vogelweide. Codex Manesse. UB Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, fol 124r.

His first works revolve around his life at the court of Frederick, Duke of Austria. The student of Master Reinmar, who was the court minstrel, was part of the ducal entourage. This meant free lodging, food and – from time to time on special occasion – a gift from the hands of his lord.

Walther was working for a wage, only medieval terminology used a different word. Walther counted on the “milte” of his lord, meaning he counted on his generosity. In exchange he provided his service.

But in 1198, catastrophe struck. Walther’s lord died on a crusade and his successor, Leopold V, thought that one minstrel was indeed enough by his standards. He preferred Master Reimar and let Walther go. Thus the young man found himself literally on the street.

The 19th century fondness of the Middle Ages made Walther a star. Unfortunately it only happened after he was long gone. Postcard after a painting by Wilhelm von Kaulbach.

Today, Walther von der Vogelweide is considered a genius poet. Unfortunately, his contemporaries could not appreciate that. The term genius would only evolve in the 18th century. During the Middle Ages, Walther was cherished as an excellent craftsman, who had invented a new type of poetry: the political poem, which should convince the audience of its commissioner’s qualities.

These were swell times for the political poet. Today, we speak of the interregnum: Emperor Henry VI had died and left behind a premature son, Frederick II, who was too young to enter the fight of his inheritance. Instead, two other noblemen stood as candidates: the Hohenstaufen Philip of Swabia and his Guelfic opponent, Otto IV.

Walther chose Philip’s side. And Philip took him in at his court. Wonderful times began for Walther. Finally, he was a member of a respected court again. Food, free lodging and a gift from time to time to attest to his lord’s “milte”. But Walther was soon disappointed: Philip was not the generous lord, Walther had dreamed of:

King Philip, those who take a close look at you, accuse you

Of not wanting to give willingly; it seems to me,

You thus give away even more.

You should rather give 1,000 pounds voluntarily,

Instead of reluctantly giving 30,000. You do not know yet

How giving can earn you respect.

Just think of Saladin and his gifts:

He said, a king’s hands should be full of holes,

Then he will be feared and loved.

Was Philip insulted by these bold words? Walther had offended him at one of his sovereign virtues. “Milte” was just as important as bravery or loyalty. We do not know, whether Walther left voluntarily due to his low wage or whether his lord threw him on the street on account of his impudence. But in any case, Walther was back on the street again.

And he wrote many stories about what that meant. About strenuous travels on bad roads, the cold, the wetness, the unfriendly noblemen, who would only reluctantly grant him shelter and a meal for his undying songs. Walther must have done what many of his contemporaries did: He sought out trans-regional feasts, where he met great gentlemen, who could maybe use one of his kind.

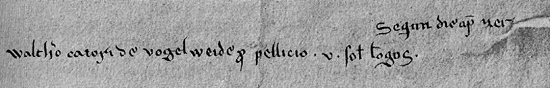

Mention of Walther in the travel bill of the bishop.

Thus, Walther was also present at the wedding of Leopold VI. We do not know, whether he was still a freelance singer and only found his engagement with bishop Wolfger of Passau there, or if Wolfger had taken him to the celebration as an attraction for his guests and let him go afterwards, since he was no longer needed. Either way, we owe the only mention of Walther in a contemporary document to this performance.

Wolfger of Passau was an important imperial politician and a clever paterfamilias. He neatly wrote down in his account book which gifts he had given out to his entourage on 12 November 1203 – the day after St. Martin’s Day – in Zeiselmauer, a small town at the Danube.

Walthero cantori de vogelweide pro pellicio v solidos longos: On this occasion, Walther received 5 solidi longi for a fur coat, not five gold coins, as one could expect, but five shillings to 30 pfennigs, ergo 150 pfennigs. That was a lot. Other members of the episcopalian household, like clergymen who served in the chancery, were given the same sum on that day.

It is worth noting that they all did not simply receive the money but instead there was a fixed purpose for it: For a fur coat. Some of the presentees might have actually bought a coat, while most of them probably saved the money for other purposes. Anyway, this small passage is a precious reference to the changing times, we are in. About 100 years earlier, no one would have received any money; they would have all been paid in or rewarded with tangibles. And some generations after this document, no benefactor would deem it necessary to attest a seeming purpose to the money he would give out.

St. Martin splits his coat. Sculpture at the Basel Minster, 1340. Photo: Jacob Burckhardt / CC BY-SA 3.0

Speaking of coats, surely this gift was not chosen at random. The ceremony took place on St. Martin’s Day after all, which was the day where interest and tributes were due and the menial staff changed their appointment. This was a day where one could once a year show one’s “milte” and what better way to do it than by hinting at St. Martin, who, as legend has it, made the grand gesture of sharing his coat with a poor man.

But back to Wolfger. He did not keep the demanding singer for too long. Soon Walther was back on the street again. The great gentlemen did not want him, the lesser ones could not afford him. A short employment for Otto IV remained a brief incident. Walther was not satisfied with his “milte” either. And thus the singer was greatly in luck when Frederick II, the boy from Apulia, needed propagandistic support in his fight for the German royal crown.

He finally gave Walther, what he had longed for – a secure source of income. In medieval times, this naturally did not mean a safe employment but rather a feoff, i.e. a piece of land, which Walther could then lease to a farmer and thus assure his livelihood. His small possession at Würzburg finally granted Walther the financial security he had always dreamed of. Now he could rejoice:

I have got my feoff, everyone, I have go my feoff:

Now I no longer fear the frost at my toes

And will appeal to miserly lords no more.

The noble king, the “milte“ king has provide for me,

So that I now have fresh air in summer and warmth in winter.

Austria. Pfennig, ca. 1190-1210, Enns. Winged panther. Rv. two dragons. From Künker sale 130 (2007), No 2595.

These beautiful pfennigs from the Middle Ages, they had only been important for Walther as long as he still had to wander the bad country roads. Now – just like a nobleman – he could live off the renders of his peasants. And most probably, he would only see pfennigs when his possessions brought out so much that he could sell the excess on the local market.

If you want to learn more about poets and their income read these articles on William Shakespeare and Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen.