A Numismatic Journey Through the History of Poland

by courtesy of World Money Fair

The Beginnings

The region between the Wartha and Vistula rivers is said to be the cradle of the Polish nation. The Polanes or Polanians, a Slavic tribe which would give its name to the country later, settled there in the early Middle Ages.

In 966, Duke Mieszko from the dynasty of the Piasts converted to Christianity. A loyal ally of Emperor Otto I, he managed to expand his territories, mainly toward the east.

Under Boleslaus I (966-1025) the influence of the Duke of Poland reached as far as present-day Ukraine. For some time, even Kiev was at his command. This considerable gain in power was confirmed by Pope in 1025 when the Duke of Poland received the title of a king.

2006 2-zlote. Rv. Piast knight on horseback. Schön, p. 1678, 604.

Then, Poland was a sparsely settled region that attracted large numbers of settlers from the already overpopulated West of Europe. They helped to reclaim the soil and develop trade. In 1226, Conrad of Masovia asked the Teutonic Order for support in his struggle against the Old Prussians, a Slav tribe living on the Baltic coast. The belligerent monks took advantage of this occasion to create a sphere of influence of their own. Together with other knights from the Holy Roman Empire, they fought on the Polish side when the Kind lead Poland against the Mongol army at Legnica in 1241.

10 zlotych 2007. St. Florian’s gate in Krakow. Rv. seal. Schön, p. 1679, 631.

Under the Piasts Krakow was the capital of the realm. It was Casimir III (1310-1370), in particular, who expanded the city and founded a university. Under his reign a stable currency and a unified legal system were introduced in Poland. The king encouraged Jews that had been driven out of western Europe to settle in his country. He secured the trade routes and is the only Polish king that was honored with the by-name “the Great”. With him the House of Piast died out in 1370. Louis I of Hungary succeeded him on the Polish throne.

Under the Jagiellons

When the latter died in 1382, rule devolved to this daughter. She married the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Jogaila, who was to become the ancestor of the Jagiellon dynasty. Henceforth, Lithuania and Poland were ruled in personal union.

2002 100-zlotych. Rv. Ladislaus Jagiello). Schön, p. 1671, 444.

Ladislaus Jagiello, as Jogaila called himself since his coronation, systematically extended the frontiers of his territories. He soon became one of the most powerful rulers in Europe, to the point of defeating the Teutonic Knights, which had been believed to be invincible, in the battle of Grunwald (1st battle of Tannenberg) in 1410, thus achieving to break the power of the Teutonic Order.

The Golden Age

Under the Jagiellons, influence of the nobles increased. The king had to largely renounce on raising taxes and meddling into internal affairs. Under pressure from the Turks, the kings made one concession after another. When, in 1493, a new crusade against the Ottomans was being planned, a Polish parliament was convoked, the Sejm, which developed to become a permanent institution. It provided that the king should be elected as head of state for the period of his lifetime and restricted his internal competences. Thus, Poland was very advanced in matters of democracy by the standards of those times. Nowhere else in Europe the nobles elected the king themselves.

2006 100-zlotych on the 450th anniversary of reformation in Poland. Rv. Polish Protestant reformer Jan Laski. Schön, p. 1678, 603.

The 16th century became the golden age of the nobles’ republic. While religious conflicts raged throughout the whole of Europe, the confessions peacefully coexisted in Poland – catholic, protestant and orthodox.

In 1505, the constitution Nihil novi (= “nothing new”) was adopted; it stipulated that all matters concerning the nobility – which was basically everything – should also be decided by the nobles. A veto right was introduced that enabled each single member of the Sejm to block a draft bill with his vote. This was to entail dire consequences when, in the course of the 17th century, the nobles’ republic degraded, as it was a downright invitation for bribery. Every neighboring state could exert influence on Polish policies just by bribing a single nobleman.

At the Hands of European Powers

When, following the death of Russian Tsar Boris Godunov, the Kremlin was occupied for two years by a Polish expedition brigade, Poland’s power was already declining.

The kings of Poland came from all European dynasties. They changed quickly and only the Swede Sigismund III Vasa (1587-1632) restored some calm to the country during his 45-year-long reign. Under him, the capital was moved to Warsaw.

It seems an irony of fate that precisely his countrymen devastated Poland during their expansion in the second half of the 17th century, reducing its population by one-third.

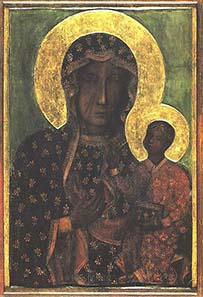

The Black Madonna of Czestochowa. Source: Wikipedia.

The successful defense of the monastery of Jasna Gora near Czestochowa became a symbol of the struggle against the Swedes. The victory was contributed to the shrine of the Black Madonna which became an important pilgrimage site in the following centuries and still today attracts a great number of religious Poles.

However, the decline of the realm could not be stopped. Ever more often would Russia and Prussia intervene to place their respective candidates on the Polish throne. Thus, for instance, a former lover of Tsarina Catherine the Great named Stanislaw Poniatowski was crowned King of Poland. He had been educated in the spirit of enlightenment and tried to reform the country. The nobility stood up against his plans.

The Russian empress Catherine II and Frederick II, King of Prussia, took advantage of this interior conflicts and annexed parts of Poland. Maria Theresa of Austria, while lamenting over this partition, calling it “a breach of everything that once was holy and just, also secured herself a large share of land. The “first partition of Poland” cost the country about one-third of its territory.

That was a shock for Poland where now reforms were pushed in a greater hurry. The State Council created the first constitution in Europe, which was the second worldwide, adopted on May 3, 1791. In doing so, however, the enlightened rulers of the neighboring states considered that Poland’s progressive politicians had gone too far. In 1793, Prussian and Russian troops invaded the country for the second time. The result went down in history as the “second partition of Poland.”

The Partitions of Poland. Source: Wikipedia.

Polish nationalists led by General Tadeusz Kosciuszkos stood up against foreign rule. But in 1793 the army of insurgents had to surrender before Warsaw. The victorious powers divided Poland a third time, this time so thoroughly that it completely disappeared from the map.

A Nation Without a State

It would take 123 years until Poland was reborn. Many nationalists fled to France. In 1797, there was a Polish legion in the French army, which Napoleon deployed in the Italian campaign. From that time originates the song that would become the country’s national anthem: Poland is not yet lost / while we live. / What foreign force has taken from us / we shall take back with the sword. / March, march Dabrowski / from Italy to Poland. / Under your command / we will reunite with the nation!

In those years, a deep relationship developed between France and Poland, despite the fact that Napoleon did not make any effort for the creation of a Polish national state. The Congress of Vienna sealed the erasure of the Polish state.

The country was divided up between the Habsburg Austria, the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Notwithstanding, Polish nationalists would make a name for themselves time and again – be it in 1830 at the November Uprising against Russia, in 1848 during the Spring of Nations against Prussia or in 1863 at the January uprising, once more against Russia. Each new defeat drove countless Poles into exile.

Back to a State of its Own

During World War I, Polish nationalist Jozef Pilsudski founded the Polish Legions, a volunteer army that soon allied itself with the Western powers. With the defeat of the three partitioning powers and the fall of their ruling dynasties, Hohenzollern, Habsburg and Romanov, the way was free to a recreation of Poland.

2008 20-zlotych on the 90th anniversary of recovery of Polish independence. Schön, p. 1682, 673.

On January 8, 1918, Thomas Woodrow Wilson held his famous “14 Points” address to the US Congress about a new order in Europe in which he also saw to the cause of Poles: “An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea.”

For such a long time the Poles had waited for a state of their own. With enthusiasm, expertise and prudent planning the politicians set out to tackle the complicated business of forging a nation from the three parts of the country. A lot was achieved, other things were neglected. Above all, it was nationalism and the diverging interests of the different ethnic groups that caused conflict. During the plebiscites in which the people of Eastern Prussia and Upper Silesia had to decide whether they wanted to be a part of Poland or Germany hostilities broke out, costing many human lives.

Also, the economic crisis contributed significantly to weakening the government and national solidarity.

Years of Terror

A secret additional protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop-Treaty provided for the division of Central Europe in a German and Soviet sphere of influence. To achieve that aim Hitler first attacked Poland. After a staged attack of SS forces in Polish uniforms on the Gleiwitz radio station, he ordered the invasion of Poland.

2009 10-zlotych. Rv. Dive bombers at the air raid on Wielun. Schön, p. 1684, 711.

The German “Führer” had calculated rightly. The French and British governments contented themselves with protesting. The question “Mourir pour Dantzig?” (Die for Gdansk?) in French became an idiom for a cause that is not worthwhile. When the Red Army also invaded Poland on September 17, 1939, a time of brutal occupation began.

Until today, the Katyn massacre, of which the Poles are still very aware, weighs on German-Polish relations. Several thousand Polish officers were murdered there on Stalin’s orders in the spring of 1940. The massacre was only one part of the extermination of the Polish elite. 22,000 people – members of the army, the police and the educated class – lost their lives.

Again, Poland was divided. Regarded as inferior by the Nazis, Poles were dispossessed and displaced to make way for German settlers. Heinrich Himmler expressed quite clearly what he had in mind for the new generation of Poles: “For the non-German population of the east there shall be no higher education than the four-grade elementary school. The sole goal of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, not above the number 500; writing one’s name, and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans, and to be honest, hard-working and loyal. I do not think that reading is desirable.”

2008 200-zlotych on the 65th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Schön, p. 1681, 661.

The new German rulers systematically murdered Polish Jews. Auschwitz near Krakow, Majdanek near Lublin and Treblinka near Warsaw bear witness to how far human cruelty can go.

2008 2-zlote on the 65th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Schön, p. 1683, 703.

The victims fought back – in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising which is much lesser known in Germany. When the Red Army was advancing toward Warsaw to “free” the territory from German rule, the people of Warsaw decided to stand up against the Germans – to welcome the “liberator” after having regained control of their own territory. They did not stand a chance. They could not match up to the German army. The uprising was crushed. 150,000 citizens of Warsaw died; 200,000 were taken to concentration camps or sent to Germany as forced labor; sites of cultural heritage such as churches and museum were systematically destroyed. Meanwhile, the Red Army stood on the other bank of Vistula river, barring their allies from supporting the insurgents with aid supplies. When the Red Army finally entered Warsaw in January 1945, only 5,000 people were alive in the ruins of the city.

The Second World War took a high blood toll from Poland. One-fifth of its population died a violent death, and about 40 percent of its national wealth were destroyed. The German inhabitants of Polish territories who had to leave their homesteads after 1945 paid the price for these infamous deeds.

Under Soviet Control

After World War II, the Polish territory moved westward – at the cost of Germany and to the benefit of the Soviet Union. For a lot of Poles, that meant they had to give up their home where they had lived for centuries. The Oder-Neisse line was recognized as the new Western border. Thus Poland seemed to be dependent on the Soviet Union. Who if not the Red Army would protect the country from German revenge? Soviet troops were stationed in Poland, to the great displeasure of the Polish population.

2008 10-zlotych. On the banishment of Polish dissidents to Siberia. Schön, p. 1681, 657.

Those who before had fought against German occupation now were involved with clandestine resistance against the communists. It was another bloody struggle that claimed about 50,000 victims, among them many intellectuals, some of which were killed, others banished to Siberia.

Stalin’s death and, above all, the famous secret speech Nikita Khrushchev held at the 20th Party Congress in 1956, in which he sharply attacked Stalin for the first time, initiated the so-called thaw in the East. Although some early concessions were soon taken back the more liberal policies of the Khrushchev Thaw led to a rapprochement between Poland and West Germany which culminated in a treaty recognizing the existent border of the Oder-Neisse line.

Memorial in honor of Willy Brandt’s genuflection in Warsaw. Picture from Wikipedia / Szczebrzeszynski.

When the German Chancellor Willy Brandt visited Warsaw in this context, he knelt down in front of the Ghetto Uprising Memorial. The Warsaw Genuflection was to become a milestone in the German-Polish relations.

On the Way to Independence

Rapprochement to the West brought the possibility of borrowing money abroad to improve the poor supply situation. Over the years, debt accumulated and required an increase in food prices. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. In 1980, numerous strikes were declared in the course of which the trade union Solidarity under its charismatic leader Lech Walesa was founded. It was the first opposition movement in the Soviet bloc to be officially recognized.

1990 100,000-zlotych on 10 years of trade union Solidarity. Schön, p. 1660, 203.

When the Polish government realized it could not repress the protest movement, it declared martial law on December 13, 1981. Walesa and other members were detained. Once more, the political opposition went underground where it could count on moral support from the free Western countries – also thanks to the intervention of the Polish pope. Lech Walesa became the figurehead of the freedom movement. While he was under strict house arrest, he was elected “Man of the Year” by Time magazine; also, he was awarded the Danish Peace Prize, the Shalom Prize by German Working Committee for Justice and Peace and eventually, in 1983, the Nobel Peace Prize.

Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from February 6 to April 4, 1989. Published 1989 / Source: Wikipedia.)

Following pressure from inside and outside the country, the old government backed down. In the negotiations at the Round Table of Warsaw, held at the center of worldwide attention from February to April 1989, it was decided to hold general elections, in which the opposition achieved a landslide victory.

Right in the Middle of Europe

In these elections, for the first time in the Eastern bloc, a non-communist head of government was brought to power. Although the road was not easy, it was the start toward a democratic constitution, eventually passed in 1997.

In 1999, Poland became a member of NATO. In 2004 the country joined the European Union, following a plebiscite with a turnout of 59% in which 73% had voted in favor.

Since then, the borders between Germany and Poland have been wide open. Now, the two countries can get to know each other better. Personal encounters and friendships between Poles and Germans could contribute to a better understanding on the political level in the future.

All photos of coins © Polish Mint.