In the Empire of The Merry Widow

‘You’ll find me at Maxim’s,’ belts out Count Danilo of Montenegro in the third act of The Merry Widow. Today’s opera enthusiasts may, however, know him better as Danilo of Pontevedra, a change initiated by the censors in an effort to avoid any unwanted references to the Montenegrin crown prince of the same name and his German consort, Jutta von Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

100-perpera piece, minted in honour of Nicola I of Montenegro in celebration of the 50th anniversary of his governance and his ascension to King.

You see, Danilo’s father, Nikola I of Montenegro, was an important ally in the Balkans. A rare 100-perpera piece with his portrait is coming up for auction during Künker’s auction week in Osnabrück between October 8th-12th.

On May 1, 1858 a massive bloody battle was fought. Grand Duke Mirko and his 7,500 men defeated a Turkish army at Grahovac, thus putting the principality of Montenegro on the political map. Only a few years prior, it was still completely unclear to whom the rugged land actually belonged. A prince-archbishop saw to the area’s secular and sacred sovereignty; the Ottoman Empire would occasionally assert their interests in the region; and the Russians acted as defenders.

It was only Mirko’s brother, Danilo, who received acknowledgement from Czar Nicholas I as the absolute ruler of Montenegro and, at the same time, asserted its territorial independence. The victory at Grahovac forced the Turks to acknowledge these new borders. The Montenegrins had become heroes in the eyes of all those who had battled against the Ottoman Empire.

Danilo himself, however, was not to get much of a chance to reap any rewards. His uncompromising enforcement of fiscal interests, combined with an ill-advised penchant for France, essentially guaranteed his political suicide from the standpoint of both domestic and foreign policy He was assassinated in August 1860.

King Nicola I shortly before his removal from office. Photo: Bain News Service 1911. Today, Library of Congress ID ggbain.04998 / Wikipedia.

The Habsburgs, the French, the Russians and the Prussians all immediately tried to use the situation to their advantage. But the new king, Nicola, son of the victor of Grahovac and nephew of the murdered Danilo, was an exceptionally gifted diplomat who had been educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris. As Prince of Montenegro, he had visited the most important courts of Europe and charmed the European women who had seen him in his picturesque uniform in the newly emerging tabloids of the time.

The marriage ties he managed to arrange for his daughters alone attest to just how successful his foreign policy was: he married two of his daughters off to Russian grand dukes; another became the consort of the Italian king, Victor Emmanuel. His oldest daughter presented a promising future option. Her husband, Peter Karadjordjevic, was a potential candidate for the Serbian throne, which he in fact ascended in 1903. This family tie could have meant further gains in power for Nicola had he not lost his most faithful defender, the Russian Czar, who instead now dedicated himself to the great Serbian.

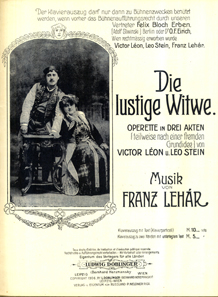

Piano score from ‘The Merry Widow’, published 1906. Source: Walter Anton Collection/ Wikipedia.

The political changes were of course felt in Montenegro. In 1905, the same year that saw the premiere of The Merry Widow, Nicola had to provide his subjects with a constitution and a parliament. At the same time, censorship was tightened so that Nicola could restabilize the situation. The testimony of this short period of rest is the magnificent 100-perpera coin, which was issued in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Nicola’s governance. In honour of this occasion, Nicola was crowned King of Montenegro on August 28, 1910.

Two series of gold coins were minted during this memorable year – one, ours, depicts the ruler as prince, the uncovered head facing right above a laurel wreath. The other presents the new king with the laurel wreath facing left. Common to both is the coat of arms on the reverse, which depicts the crowned two-headed eagle with the royal insignia. On the breastplate, a lion walks to the left. This coat of arms is now used again today as the national coat of arms of Montenegro.

Three denominations of both types were issued, a 10, 20 and a 100-perpera piece. In terms of weight, they correspond to the Austrian kronen standard. While as many as 30,000 to 40,000 pieces of the 10 and 20 perpera pieces were minted, only 500 (or in our case, 301) pieces of the 100-perpera pieces with a weight of almost 34 g gold were produced. We’re dealing here with a great rarity that signifies the kingdom of Montenegro’s final heyday.

In 1912, Nicola found himself forced to join the Balkan alliance against the Ottoman Empire. In consultation with its allies, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Porte on October 8, 1912. It proved a catastrophe for the king – the Montenegrin army suffered great casualties and the only noteworthy gain in territory had to be returned, as per the objection of the European powers. The situation wasn’t much better during the First World War. While the troops bled and paid heavily with their lives, the royal family took precautionary measures and went into exile. It was there that Nicola I learned that his national assembly had decided to unite with Serbia. The deposed king remained in France, where he died in 1921 at the age of 79.

You will find Künker’s Fall Auctions from October 8 to 12, 2012 with all relevant information here.

The complete catalogue is also available online.