The Design of the Circulation Euro Coins: Italy – 1 Cent – Castel del Monte

translated by honeycutshome

The euro coins are a splendid means for all countries in the eurozone to convey their own self-conception. Why did the Italians choose to depict solely works of art on their euro coins? And how important a role does famous Castel del Monte, built by Frederick II, play in Italian national identity?

In its coinage, Italy praises itself as being an important cultural nation. The reason might lie in the ambivalent relationship of the Italians to their state. The Lega Nord advocates secession of the North, every inhabitant of Southern Italy seriously distrusts the government in Rome, and the Roman central government has its problems in making its decisions palatable to the citizens, in short: in every-day life, the state in Italy is more an obstacle in normal life than a unifying community. Hence, national symbols just like the ones that appear on other European euro coins – just think of the German federal eagle and the oak leaves – are like a fish out of water in the Italian euro emission.

In Italy, another path was pursued to depict symbols of the Italian unity on coins: it was decided that the achievements of the great cultural nation ought to be praised; be it Milanese, Roman or Palermitan: all Italians without exception are proud of their works of art!

Castel del Monte, the most renowned building of Frederick II. Photograph: Travus / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

The smallest Italian denomination, the 1 cent piece, depicts Cast del Monte on its reverse, an edifice built by Frederick II. Why, of all buildings, was this castle chosen to represent Italy in the coin design? What is so unifying about it, appealing to all Italians? What connotations are associated with Castel del Monte?

To answer these questions, we have to go back more than 750 years, to an era when half of the world was ruled from Southern Italy.

The birth of Frederick II. Source: Wikicommons.

Indeed Southern Italy used to be the center of the then world, when a little boy from Apulia set about uniting half of Europe under his rule. Back then the Kingdom of Sicily not only comprised the island itself that bears this name up to the present day, but Apulia, Campania and Calabria, in short: the whole of Southern Italy up to the dominion of the Pope. That was the territory Frederick II inherited from his mother, the last heir to a great dynasty that had become extinct unexpectedly. From the other side, he inherited the claim to the German royal throne, because his father, Emperor Henry VI had had Frederick elected King by the German princes when he had just been an infant. This is not the place to elaborate on the rise of Frederick II. It was adventurous enough. Simply put: the boy from Apulia became the most powerful ruler in all of Europe. His politics affected the entire then known world, he reorganized the German Empire, reconquered Jerusalem for the benefit of Christianity – at home, however, he felt only in his beloved Apulia.

Southern Italy had been a particularly difficult legacy for Frederick. His father had died early, and during his childhood the nobility had tried to usurp major parts of Frederick’s royal rights. Dukes, counts and knights – they all had built castles at places they weren’t allowed to, they had converted the revenues from royal taxes and privileges tacitly to their own use, administered justice although they weren’t entitled to and simply had acted as if they had had no superior ruler. Frederick had experienced firsthand the weaknesses of the medieval state in which everyone only cared for number one. Thus, he decided to create something new.

Frederick II with his falcons. From his book “De arte venandi cum avibus” (“On The Art of Hunting with Birds”) from the late 13th century. Source: Wikicommons.

At this point, we have to say a few words about the character of Frederick II. He seems to be the one medieval ruler closest to us ‘modern’ people. It was he who put the experiment, nature watch at the center of realization, who tried to solve every problem with logic. His book on hunting with falcons is full of testimonies to his gift to learn from nature, to disregard the old authorities in order to draw conclusions from watching. It has been stated that this ability of Frederick II stemmed from his being born in a place where many cultures clashed. Palermo, for example, was one of the most colorful cities of the then known world where dealers from Orient and Occident met to buy and sell goods, where intellectuals met and people of many diverse faiths talked with each other. Frederick is rumored to have hung around in this city, was forced to let himself be invited by wealthy merchants for lunch unattended. That certainly isn’t the truth but malicious propaganda of a hostile Pope who wanted to deny the emperor a thorough education. Frederick in turn is highly likely to have benefited from the urbaneness of the people he came to meet when he was a young man.

Hence, Frederick was given the chance to reorganize his beloved Southern Italy devoid of reservations. He accomplished that in a way that became a model for the modern state we are living in. First of all, Frederick monopolized the power for the king. In 1221, he enacted a law stipulating that the old fortresses that had been built by some minor princes had to be committed to him. Most of these he destroyed but some he rebuilt to become royal fortresses. In doing so, he breached one of the most essential laws of the feudal society. Up to that moment, fortresses – together with the territory from which they ought to be financed – used to be delivered to loyal followers. This of course involved the danger that such followers might defect to an enemy and deprive the king of key positions of high strategic importance. Frederick didn’t want to take any risk, so he handed the fortresses over to regulars and financed maintenance, supplies and personnel himself. In addition, the fortresses normally were guarded by just a limited number of personnel. The emperor only sent re-enforcements in a crisis situation.

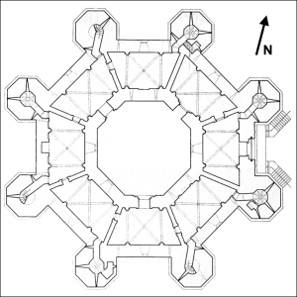

Octagonal footprint of Castel del Monte. Source: Travus / Wikicommons.

As a matter of fact, Frederick had new edifices built, too. One of these is Castel del Monte, that certainly had been under construction in 1240, probably drawing close to completion. This building perhaps mirrors best the rational thinking of the great emperor. This building has often been taken as reflection of the planning mind of Frederick who greatly enjoyed both arithmetical exercises and logic. An octagonal building framed by eight towers who likewise have an octagonal layout surrounds an octagonal inner court in whose center there is said to have been a fountain once. In the Middles Ages, the eight was one of the Christian numbers. We only call to mind the octagon of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the octagonal layout of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen that had been built by Charlemagne. Frederick had seen both buildings with his own eyes, and he been impressed by their indescribable aura.

Local historians with a spiritual interest are trying today to link Castel del Monte to a mythology based on numbers that might have been intended in the first place – although certainly not to the degree some people credit it with. Some even considered the castle a center of initiation where Frederick II had created a new religion alien from Christianity and Islam. Such extravagant theories are fostered by the fact that no one can really imagine what the original function of this magnificent building might have been. Apparently, it played no part in the defense of Apulia and mainly served as prison after the death of the great emperor. So, what is Castel del Monte? Defense building, hunting lodge, symbol of imperial grandeur? Perhaps we will never know for sure what smart Frederick had in mind when he built this castle.

Actually, Castel del Monte continues up to the present day to embody everything Frederick has achieved in his state: a ruler that wasn’t above the law but subject to it and established laws for the good of his people; a class of paid officials responsible for administering under the close supervision of the emperor; the possibility for every citizen of the kingdom to lodge a complaint against state officials; a unification of the law in a state in which all citizens are granted justice according to their estate; the chance for gifted people to rise in the service of the king and an emperor aiding them by founding a local university and generously awarding grants for the education. Frederick curtails the right to carry arms in his empire, prohibited private vendettas and acts of personal revenge. In addition, he took care of the ones without protection: anyone in distress was allowed to appeal to the king, and a disregarding attacker was severely punished by the king.

All these laws tell of the new era Frederick II planned to usher in. But Frederick failed. In the fight against a papacy that was afraid of the secular state and – for the sake of maintaining its own power – battled the emperor until he fell, Frederick went down. His descendants were eradicated, killed, and the grandchildren of Frederick were imprisoned in Castel del Monte until they died.

View of Castel del Monte from 1844, painting by Victor Baltard. Source: Travus / Wikicommons.

The Italian state bought Castel del Monte, that was in a ruinous state by then and used by shepherds, villains and political refugees as shelter, as late as 1876. The owner were paid 25,000 lira, a knockdown price since even the most necessary renovations cost that very sum. Today, visitors from all around the world come to trace the spirit of Frederick II of Sicily in this building, of the man that ruled half of Europe and who seems to have been way ahead of his time. They see a gorgeous testimony to an era when Apulia, today a poor country that mainly lives on agriculture, used to be the center of the world: when Europe was controlled by Southern Italy that experiences a short bloom but then fell into a deep sleep from which it hasn’t awaken yet.

Did you know that the Castel del Monte is enlisted as UNESCO World Heritage?

Several websites are also dedicated to it, for instance this one.

Find out more about the life of Frederick II in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

none