Numismatic Bookplates – a Wonderful Field of Collection

Even in medieval monasteries, the most precious codices did not simply lay on the shelves but were chained to lecterns. This made a basic need of every enthusiastic reader impossible to satisfy: acquiring the book with which one had such an affectionate relationship. A bookplate, or ex-libris (Latin for “ex” and “libris”, thus “from the books of”), is the modern way of chaining books. It makes it more difficult to snatch a book from a library because every time the book is opened, the reader immediately sees who its actual owner is.

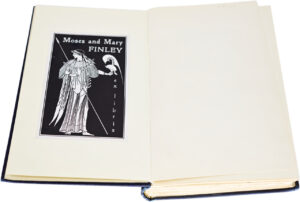

The ex-libris of husband and wife Moses and Mary Finley, stuck into a rare book by J. M. F. May, The Coinage of Damastion. Oxford (1939). Estimate: 125 euros (No. 111).

Bookplates as Status Symbols

The oldest bookplates can be traced back to the end of the 15th century. They experienced their first golden age in the Renaissance period, when they became a status symbol. People carefully thought about what to depict on them. Even highly renowned artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach or Hans Holbein did not believe that designing ex-libris was beneath their dignity. Since then, bookplates have never ceased to exist. However, there were obviously times during which they were more or less common.

The fascination of ex-libris lies in the fact that they summarise on a few square centimetres what their owner considered to be especially remarkable about his personality. And this can have much to do with their lives, as the bookplate of world-famous historian Moses Finley demonstrates. Of course, Athena refers to the period he focused on in his research. However, much more remarkable is the fact that there was an ex-libris in his “own” books bearing not only his name but also that of his wife. Despite being childless, he led a fulfilled and happy life with her. How close their relationship was after more than 50 years of marriage is illustrated by the fact that Moses Finley suffered a stroke one hour after discovering that his wife had passed away, and he died the following day.

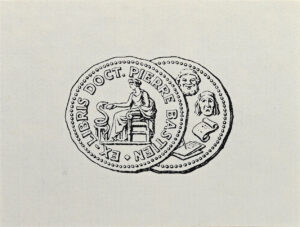

Pierre Bastien’s bookplate, stuck into the extremely rare publication on the collection of Carlos de Beistegui. Paris (1933). Estimate: 750 euros (No. 1).

How to Read a Bookplate

Thus, ex-libris illustrate the personality of their creator and depict them as they liked to see themselves. That is the reason why even someone who hasn’t read any of Pierre Bastien’s more than 180 works can tell from the shape and the motif of his ex-libris that numismatics played an important role in his life. The depiction of Hygieia refers to Bastien’s bread-and-butter job: he worked as a surgeon until he retired. It is tempting to interpret the two theatre masks on the right as the two different parts of his life.

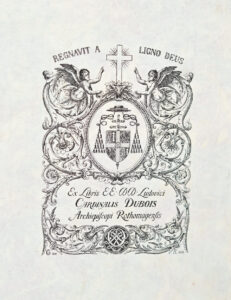

The bookplate of Louis-Ernest Dubois, Cardinal and Archbishop of Paris, stuck in three works on the history of the Netherlands published in Amsterdam in 1723. Estimate: 200 euros (No. 333).

Whoever sees this bookplate immediately realises that it must have belonged to a man of the church. The cardinal’s hat is clearly recognisable and represents the highest ecclesiastical office held by the owner of this bookplate. Above it, between two winged putti, a cross with the Latin inscription “Regnavit a ligno Deus” (God has reigned from the tree). The quote stems from a hymn in honour of the Holy Cross by Venantius Fortunatus (about 530-609). The hymn deals with the sacrifice of Christ, which became the greatest triumph of mankind.

We do not have to think long about what Louis-Ernest Dubois (1856-1929), the owner of this bookplate, wanted to say by means of the ex-libris. He lived in a time when the fundamental separation between church and state became reality. He placed himself at the service of the state, nevertheless, he advanced within the hierarchy of the church: he became bishop of Verdun, archbishop of Bourges, cardinal and archbishop of Rouen and, finally, archbishop of Paris. This bookplate must have been created between 1916 and 1920 as it bears the title of the archbishop of Rouen.

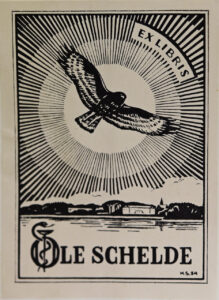

Ole Schelde’s bookplate stuck in all three volumes of the important Danish work on Roman coins: Rudi Thomsen’s Early Roman Coinage. Copenhagen (1957-1961). Estimate: 100 euros (No. 231).

The ex-libris of Ole Schelde (1913-1982) displays a completely different mentality. The Danish coin collector chose a bird flying towards the sky above a wide, open landscape. His medical profession was incorporated in the form of a vignette in the first letter of his name: a snake curled around a bowl on a rod.

Henry Michaelis Hallenstein’s ex-libris stuck in the catalogue of Greek coins of the Hunter Collection / Glasgow. Glasgow (1899-1905). Estimate: 750 euros (No. 109).

The fact that Henry Michaelis Hallenstein (1872-1922) collected Greek coin is not only shown by the book in which his bookplate was stuck, but also by the depiction itself. The Athenian owl speaks for itself. Hallenstein possessed sufficient means to afford this field of collection, which was already very expensive in his time. At the end of the 19th century, his family, which originally came from Germany, was one of the most important dynasties influencing New Zealand’s economy.

Charles M. Johnson’s bookplate stuck in Babelon’s work on the coinage of the Roman Republic. Paris / London (1885/6). Estimate: 150 euros (No. 190).

An Unlucky Deal… Or Wasn’t It?

The bookplate of Charles M. Johnson hardly tells us anything apart from the fact that he loved books. Fortunately, George Kolbe explains in his work Reminiscences of a Numismatic Bookseller how Johnson’s library returned to the market.

In 1979, George Kolbe went to Long Beach in order to make an offer for the library of coin collector Charles Johnson. The library was huge and the collector had built a separate extension for it. George Kolbe made some calculations and presented the offer, which was immediately accepted by the collector. Unfortunately, the sale did not take place. Charles Johnson died that very day before any contracts were signed. His family sold all books on ancient and European numismatics to Douglas Saville at Spink. George Kolbe was left with the books on American numismatics. But, as he wrote himself: “Charles Johnson’s son in real life was proprietor of a used car emporium. I was no match for him.” In the end, George Kolbe paid much more than the books were worth at the time of sale. And yet he was lucky. He purchased the books at the exact time when the price of numismatic literature started to go through the roof.

Discover Your Love for Collecting Books, It Is Worth It!

Books are an investment, just like coins. The value of a numismatic library is similar to that of a share. It can rise, and it can fall. But regardless of its current material value, every library is not only a tool but also a means of reassurance. It represents the fact that numismatics is part of a centuries-old tradition. There were generations of coin collectors and numismatists before us. And there will be generations of coin collectors and numismatists after us.

No matter whether we purchase a book or a coin, it is nothing but a loan that we guard during our lifetime on behalf of the large community of collectors and that we will eventually pass on.

Here you can find our preview for the auction sale of Alain Poinsignon’s numismatic library.