The People of Zurich and their Money 5: The Soldier’s Wages of Pavia

by courtesy of the MoneyMuseum

Our series ‘The People of Zurich and their Money’ takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. This time around, it’s the year 1512 and we’re standing in the chamber of the Abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey. She is hiding a mercenary leader who’s on the run. Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of ‘making of’ – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to help underscore and illustrate its context.

1512. Katherina of Zimmern abbess of the Fraumünsterabtei hides the commander of the Zurich squad captain Jakob Stapfer in her cell. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Äbtissin: (out of breath) Hurry up, in here.

Hauptmann: (terrified) Good heavens, they are coming!

(resolute) No, they wouldn’t dare do that. No citizen of Zurich would enter the cell of the abbess of the Fraumünsterabtei without her permission. Don’t be afraid, you’re quite safe here. Tell me, what’s going on?

My own lansquenets want to kill me.

Why?

They accuse me of embezzling part of their wages.

The pay of the Pavia campaign?

Yes. But they’re wrong! I never received the money! You know how these noble lords are: They deliver great speeches to the soldiers, promise gold, gold and gold again. But when they should pay gold to the captain, all of a sudden they can’t remember their promises.

Hang on, not so fast. I don’t understand who had to pay the wages to whom.

Listen, cardinal Schiner persuaded the assembly of the Swiss cantons to make an army of 18,000 soldiers available to the Pope. Of course a Zurich squad took part. I was in command.

I know.

Being captain I was responsible for paying of the wages. After all, the Pope wouldn’t personally hand each lansquenet of Zurich his 2 ducats per month. The papal paymaster gave the total amount to me and I had to get even with my soldiers.

That’s clear.

After the victory of Pavia, cardinal Schiner promised that an extra 12 wages should be paid to every 100 soldiers. He told me that I should keep two of them for myself and that I should distribute the remaining 10 to my men.

In other words: The soldiers were to receive 10 percent more than their normal pay; and they presumed that they were entitled to more.

Yes, and then the number of soldiers from the list of Schiner did not correspond to the actual number. And the payment has never been fully paid. But nobody is interested in these facts. Everybody wants his money from me.

I can’t imagine that you got the worst of the deal, even when the payment wasn’t fully made.

I got my share, but I certainly wasn’t any more dishonest than any other captain in the Swiss army.

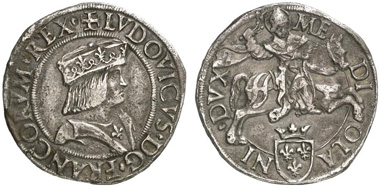

Louis XII as Ludovico XII of Orléans, Duke of Milan, 1500-1512. Testone undated, Crippa 3/A. From Künker auction 183 (2011) 1799.

Making of:

In March 1510, the Swiss Confederacy along with Pope Julius II entered into an agreement allowing the chief church pastor to hire mercenaries in Switzerland for five years to protect the Holy See from all potential enemies. With this, the Swiss Confederates made a definitive break with Louis XII of France, who, in 1500, had still been enforcing his hereditary inheritance claims on the Duchy of Milan with the help of Swiss mercenaries. This political about-face was preceded by disputes between the Swiss Tagsatzung (‘Swiss Diet’) – a meeting of the delegates of the individual cantons of the Confederacy – and the French king, who had been withholding contractually regulated trade benefits from the Swiss Confederates. They in turn saw this as a threat to their own best interests. Lombardy was traditionally the most important sales market for Swiss livestock products, and here, grain, rice and wine could be obtained in the event of bad harvests.

Julius II, Pope 1503-1513. Giulio undated, Rome. From Künker auction 217 (2012), 2645.

In 1512, an 18,000-men-strong Swiss Confederate army marched towards Italy and, on June 1, 1512, forced the surrender of the French occupied cities of Cremona and Pavia. Milan surrendered as well. And so, within just a few weeks, the French troops were almost fully driven out of Northern Italy.

Baron Ulrich of Hohensax took supreme command over the Confederate army; he was supported by Captain Jakob Stapfer of Zurich, who was entrusted with command over the Zurich contingent. Amid much honour and celebration, Stapfer brought the gifts of the pope back home to the people of Zurich: a ceremonial sword and a ducal crown that can still be admired today at the Swiss National Museum.

Allegory of the Reislaufen (“going to war”) and its social consequences: Left, a prosperous Confederate Reisläufer (literally, “one who goes to war”), as they’d been known since the Late Middle Ages, right, an invalid beggar, 16th century. Source: Wikipedia.

Shortly after Stapfer’s homecoming, however, rumours began circulating in Zurich. The captain had collected more money for wages from the pope than he had actually paid out to the Zurich Reisläufers, and the outraged Reisläufers demanded their outstanding pay. Stapfer’s opponents attacked him in the street. He fled to a church, seeking asylum, but not even this could put an end to the attacks of the furious Zurich Reisläufers. It was only the energetic intervention of Katharina von Zimmern, Fraumünster Abbess from 1496 to 1524 that saved the captain’s life and also provided the inspiration for our audio drama. The determined woman hid the hunted captain in her own chamber. From there, Stapfer managed to escape to safety to Zug, his mother’s hometown.

It’s possible that the charge of embezzlement was a result of the dual role held by every leader of a troop of soldiers during the Late Middle Ages. Not only were they responsible for the military command, but they also acted as chief purser. The leader assumed control over the payment of wages, which were passed on to him by the Reisläufers’ contractor for distribution among his subordinates.

After Stapfer’s escape, the trial for the onetime hero started getting underway in Zurich. Important witnesses were called upon to provide written statements, including Matthäus Schiner, Cardinal of Sion and most important partisan of the pope in Switzerland, and Baron von Hohensax, leader of the Swiss Confederate troops. On November 10, 1512, Ulrich von Hohensax sent the payment lists to Zurich city council. These were needed in order to determine whether all the men that appeared on the list had actually participated in the campaign and received their rightful wages. Matthäus Schiner furnished particulars regarding the surplus wages – the money that had been paid out following the victory –, which had been a source of great controversy. He stated that he had approved 12 surplus wages for every 100 men, from which Stapfer was to distribute 10 of them to his men and was permitted to use the remaining two at his discretion.

On December 26, 1512, a verdict was issued whereby Stapfer was sentenced to hand over the money due on paper to the Zurich Reisläufers, including, incidentally, the full twelve surplus wages per 100 men. In addition, Jakob Stapfer was given a penalty of 400 gulden for misappropriation of wage funds.

The captain refused to accept this verdict, pointing to the fundamental problem faced by all mercenary leaders: The contractor had not paid the amount that they had promised. The infamous 12 surplus wages had been distributed, albeit not to the basic team, but rather to the standard bearers and councils assigned to him. He had taken the eleventh and twelfth as his share, to which the standard bearers and councils had given their consent. He said that he himself had only taken at most 1,000 gulden away from this campaign, and even if he’d wanted to, would not be able to meet the charges he was faced with.

Fortunately, Stapfer had powerful friends who put pressure on Zurich to reopen the case. Several Swiss Confederate cities and communities spoke out in favour of the popular captain, as did the Tagsatzung and the Doge of Venice.

Cardinal Matthäus Schiner in a contemporary engraving. Source: Wikipedia.

Zurich city council reopened the case and investigated further. They found that there were discrepancies between the payment list of Matthäus Schiner, according to which the wages had been paid, and that of Jakob Stapfer, according to which the funds should have been distributed. There were substantially more men on Stapfer’s list than on Schiner’s. In addition to the officially recruited Reisläufers, Stapfer had also recruited men without the promise of a wage, for whom the prospects of pillages and rich booty were incentive enough to go to war. With the help of Schiner’s ‘official’ payment list, some of the outstanding claims against Stapfer could be dismissed.

In any case, in 1514, the matter was presented very differently to Zurich council. A commission now adjudicated that Stapfer had been done wrong. The surplus wages had to be returned by everyone who received them, but apart from that, the mutual claims were to be considered as settled. Stapfer’s penalty was withdrawn.

Stapfer did not take part in the Battle of Marignano, however. The people of Zurich weren’t so quick to reinstate him as a regular captain. But all the same, he led the Freiknechte (Swiss Infantry), the mercenaries who were not part of the official Zurich contingent, but had hired themselves out as independent Reisläufers. This proved lucky for Stapfer. The battle was lost, leaving the Swiss with a high death toll, but Stapfer survived.

Stapfer remained in the war business. He was hired on by Eberhard von Reischach as captain of an army of 10,000 Reisläufers that Ulrich of Wurtemberg is said to have supported. Zurich council, however, had decided to put a stop to Zurich natives from taking privately service in order to establish a national monopoly on the hiring out of mercenaries. Eberhard von Reischach was therefore used as an open warning to all – he was excommunicated and sentenced to death in absentia. What exactly happened to Jakob Stapfer, however, is unclear. In any event, the way in which he had been treated in Zurich ultimately prompted him to bid a final adieu to his hometown. He entered into the service of the St. Gall monastery and renounced his Zurich citizenship in the year 1522.

In the next episode, which takes place around the same time period, you’ll learn about the cost of the salvation of one’s soul – provided that one was willing to seek refuge in the selling of indulgences. And as the next dialogue shows, husband and wife didn’t always share the same point of view in this respect.

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.