The bone – or rather stone – of contention

translated by Christina Schlögl

On 25 June 1991, the Slovenian parliament declared its independence from Yugoslavia. The reasons for this step were of economic nature. Slovenia and Croatia were the most developed constituent republics within Yugoslavia. When economic slowdown started after Tito’s death, the North made the South responsible, which was traditionally dominated by the Serbians. They denied the Croatian State President the rotational takeover of the state presidency chairmanship in May 1991 in order to avoid dealing with the claims of the North. One month later, the Northern constituent republics declared their independency of Slovenia and Croatia.

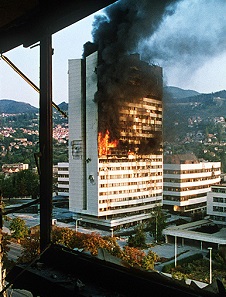

The government building in Sarajevo was on fire during the besiegement in 1992. Photo: Mikhail Evstafiev / CC BY-SA 2.5

A cruel war followed, which should spread all over Yugoslavia. Slovenia got lucky. The fight for independence took place without too much bloodshed there. The armed conflicts lasted for 10 days. They cost the lives of eight Slovenian policemen, five civilians, ten foreigners and 39 Yugoslavian soldiers.

Through mediation of the European Community, the Brioni Agreement was formed, which determined that Yugoslavia was going to pull out troops if Slovenia would wait another three months until declaring independence. On 7 October 1991, it was time. The Slovenians became independent.

1 tolar from the first money emission of Slovenia, year of issue 2004. Photo: Armin Michael Kohlross / MA-Shops.

The tolar

On 4 January 1993, the first coins of the young Slovenian republic were issued. One Yugoslavian dinar was equated with one Slovenian tolar or 100 stotinov. The subjects were noncommittal: olm (10 stotinov), long-eared owl (20 stotinov), honeybee (50 stotinov), river trout (1 tolar), chimney swallow (2 tolarja), Alpine ibex (5 tolarjev) and horse (10 tolarjev).

The non-binding nature of the subjects was precisely calculated. After all, Slovenia was cut off its most important economic zone. The war was still going on in Croatia by the time the coins were issued. And the question, if and when Slovenia could reenter into peaceful trade relations with other constituent republics of Yugoslavia would stay unanswered for quite some time.

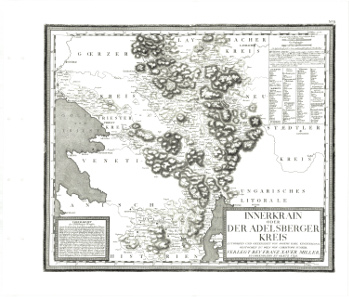

Historic map of the Carniola, as Slovenia was called when it was still part of the Habsburg monarchy. From Josef Karl Kindermann, Christoph Junker (Stecher), Gerhard Michael Dienes – Atlas von Inneroesterreich.

Thus, the aim was to open up new markets. And what else would stand to reason but to start with Carinthia and Styria with whom Slovenia shares most of its border? And here is where it started getting tricky, because this border is a remnant of the 19th century. Up until the Early Modern Age, the separation of Austria and Slovenia had not been as strict as it is presented to us today. An Austrian study from the middle of the 19th century, which rather underestimated the percentage of minorities, resulted in the following figures. For Carniola, later Slovenia: 88% Slovenians, 8% Germans. In Styria, it was 64% Germans and 36% Slovenians, in Carinthia 70% Germans, 30% Slovenians, and for Trieste and its surrounding area 55% Italians, 31% Slovenians and 10% Germans.

The Slovenian percentage outside of Slovenia only radically reduced when their sense of national identity finally caught on at the beginning of the 20th century. While 82,000 people had still identified as Slovenians in South Carinthia in 1910, it was only 37,000 in 1923. In 1939, one year after the annexation of Austria through Hitler-Germany, during a phase of forced Germanisation, only 7,443 people remembered their Slovenian forefathers.

Of course this does not change the fact that countless Austrians have Slovenians in their family tree and vice versa.

The Prince’s stone, on display at the Großer Wappensaal, Landhaus Klagenfurt. Photo: Johann Jaritz / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Shared heritage

The shared heritage manifests itself in a shared piece of inheritance – the Prince’s Stone (German Fürstenstein), a political relic of the Middle Ages, which both the Slovenians and the Austrian State of Carinthia lay claim to.

The Prince’s Stone plays an important part in the inauguration of the Carantanian prince. Until the year 828, the Prince would vow to honour the will and rights of the people in Slavonic language. The later rulers of Carantania or rather Carinthia, namely the Habsburgs, kept this ceremonial alive until 1414. That is why the Prince’s Stone is still in Austria until this day.

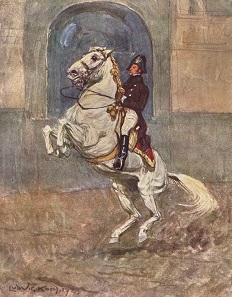

Classical dressage with Lippizaner horses. Oil painting by Ludwig Koch.

And this is not the only common feature. For centuries, Slovenia was part of the Habsburg monarchy. Not only does the Austrian cuisine have numerous Slovenian specialties, like the Carniolan sausage (“Krainer”). The stud farm Lipica also provided the studs for the Spanish Riding School in Vienna.

Thus it was and still is difficult to divide Austrian and Slovenian heritage.

The Slovenian 1 cent coin.

The bone – or rather stone – of contention

On 1 January 2007, Slovenia introduced the Euro. And the expressionless images of the first emission of Slovenian circulation coins were substituted with new coins that better suited the Slovenian national consciousness. Only the white stork on the 1 cent coin was reminiscent of the non-binding nature of the first emission. It had already been on the 20 tolarjev circulation coin since 2000.

The Slovenian 2 cent coin.

It was the Prince’ stone, depicted on the 2 cent coin, which caused most of the political discussion. The populist governor Jörg Haider protested heavily. He emphasised Carinthia’s entitlement to the stone and had it transferred from the Carinthian State Museum to the state government of Carinthia in the same year. Since 2007, following his initiative, the Prince’s Stone is thus depicted on all official documents and the stationary of the state Carinthia as a symbol of the state government.

The Slovenian 20 cent coin.

The impact regarding the 20 cent coin was not as deep, although there was slight upset in Vienna. Why should the proud Lippizaner horses that had been on the Austrian 5 schilling coin for decades now be a symbol of the Slovenians?

The force of habit

By now, the Slovenians have been using the Euro for 10 years. Most people have got used to the subjects on the coins. Only sometimes, during the silly season, does a report fill the magazines. In January 2012, for instance, the Kärtner Landesmuseum reported that “this question, that is so important for Carinthia and Slovenia, has been tackled in cooperation with special departments of the Slovenian Academy of Science and the Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt. Working together, the Prince’s Stone question has been scientifically solved.” The stone – according to archaeologists and building historians – could not have been used as a oathing stone in the 8th and 9th century, because it had only been brought to the Karnburg during the building of the fortress of Virunum around AD 1000. Naturally, the Slovenian side immediately reacted and said that this was simply nonsense!

All these historians and journalists seem to be forgetting the fact that the history of objects is not determined by their real past but is instead generated by people’s attributions to them. The ideal of a nation has only been around since the 19th century, when people started using archaeology and history to dig up – or rather to come up with symbols underpinning the state. During the course of this mission, they forgot that it is unhistoric to transfer a modern concept of nation on past times like the Middle Ages, which had completely different notions all together.

Every time must rewrite its history. Historic research cannot be neutral, because we keep using our own beliefs as projection surface.