A Visit to Alesia

by Ursula Kampmann, translated by Maike Meßmann

“Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres” – with these words, most Latin students shift from textbooks to “real” texts written by ancient authors. For centuries, the Bellum Gallicum has been considered an ideal starting point to explore ancient literature. Caesar’s sentences are short and manageable, and have been used since the Middle Ages to torment students. The side effect: hardly any other period of Roman history is as well known among former Latin students as Caesar’s campaign in today’s France. Names such as Alesia, Gergovia and Bibracte evoke associations – although only a few people still know where these places are located and what actually happened there. In this article, we take you to the most popular of them: Alesia, where Vercingetorix suffered the decisive defeat against Rome.

Content

The MuséoParc Alésia

The MuséoParc Alésia opened in 2012. As the name suggests, the museum does not want to be a typical museum but also includes a park. A highly-renowned architect was commissioned for this purpose, and he created a building that ambitiously dominates the landscape. Of course, there is a theoretical foundation to every detail of it. “Its circular form evokes the siege of Alesia, the netting that clads the building provides a nod to the wooden fortifications used by the Romans, whilst the oblique columns of its atrium recall the chaos of the battle itself”, as the museum’s website explains. And the small booklet sold as a museum guide in the souvenir shop goes on to state that the asymmetric structure of the ground floor is supposed to evoke the chaos of the siege, from which the stability of a new Gallo-Roman culture was to emerge.

Well, I am always a little sceptical when it comes to such prestigious museums. And yet, the MuséoParc managed to truly amaze me within a few minutes – for the first time ever, I really understood what happened during the battle of Alesia.

Denarius by Caesar from 48 BC. It depicts the portrait of a Gaul, who is erroneously described as Vercingetorix in many auction catalogues. In fact, it is merely a symbolic figure for some Gallic warrior. Caesar wanted to show his peers what threatening warriors he had to face in the Gallic War. From Künker auction 257 (2014), lot No. 8829.

Caesar, the Gallic War and Alesia

But let us get back to Caesar and his Gallic War. Let us remember: after his controversial consulship in 59 BC, Caesar became proconsul with the firm intention of launching a major war, so that he could match the achievements of his rival Pompey in terms of propaganda. For this purpose, he had himself assigned to the provinces of Illyria, Gallia Cisalpina and Gallia Transalpina, which offered plenty of potential for conflicts and came with the command over an impressive army.

Caesar had actually looked for a reason to start a war in Illyria, but the Helvetii did him the favour of leaving their territory in search of a new home. On their way, they wanted to pass the territories of the Haedui, who had an alliance with Rome. Caesar managed to use this people to his advantage: the Haedui asked Caesar for support, and the latter pretended that there was a danger to Rome and waged a short war. What happened next could be compared to one of those complex situations where touching one little domino leads to the fall of hundreds of thousands of other dominoes. Caesar defeated one Celtic tribe after the other. Their chiefs had to swear allegiance to the Romans one by one.

Only Vercingetorix of the Averni people was able to unite Celtic tribes in an alliance against Rome. This was the first time for Caesar to face an army that outnumbered his own, and that actually defeated him at Gergovia. But this loose alliance did not stand a chance against Rome’s military machinery. In the summer of 52 BC, a defeat forced Vercingetorix to flee with his warriors to Alesia. The oppidum of the Mandubians, one of the countless Celtic tribes that inhabited Gaul at the time, was located there.

Building Roman Fortifications

Vercingetorix had 80,000 soldiers, if Caesar is to be believed. The latter had twelve legions himself, i.e., between 50,000 and 60,000 men including auxiliary cavalry troops. It was mainly the latter that prevented the success of a first attempt of Gallic horsemen to break through the Roman lines. Caesar then built siege fortifications around the city to starve Vercingetorix and his allies. To thwart any Gallic attempt of breaking the siege, Caesar ordered his legionaries to set up two lines of fortifications and secured them with more than twenty camps.

What I translated rather thoughtlessly as a schoolgirl, filled me with deep admiration when I visited the MuséoParc. The exhibition includes two reconstructed parts of this embankment structure, which were built in their original height.

So, I stood in front of two about 3-4-meter-high earth embankments that were crowned with pales and towers. Explanatory signs told me that this embankment was just the tip of the iceberg. The legionaries had dug deep trenches in front of them – one was filled with water of a nearby river, the other remained dry. But this was not enough for Caesar: in front of and between the trenches, mantraps, chevals de frise and deep pits with sharpened wooden spears awaited the attackers.

I obviously wondered how Caesar’s legionaries managed to build the embankments and dig hundreds of holes at record speed in addition to their guard duties. Although the reconstruction is just about one hundred meters long, the original fortifications surrounded the entire mountain. That means that the inner embankments, which were supposed to prevent the Gallic troops from escaping, covered a distance of 15 kilometres, while the outer rampart, which defended the Romans against a potential relief army, was 21 kilometres long.

I am certainly not a fan of Caesar, but this logistical masterpiece commanded my respect!

The Battle of Alesia

While the legionaries were busy digging holes and chopping down trees, Vercingetorix sent his messengers to allied tribes in order to mobilise a relief army. He took advantage of the short time in which the Roman defence was not yet able to prevent individual horsemen from breaking through the fortifications.

After about two months, an impressive army of 240,000 infantrymen and 8,000 horsemen came to the aid of Vercingetorix – although we have to bear in mind that we have these numbers from Caesar, and he obviously wanted to impress his fellow Roman citizens. So, it is safe to assume that he exaggerated enormously. Fake news is not an invention of our age.

The infantry of the relief army attacked the Romans, but the legionaries were able to defend their position. On the next day, the relief army and the besieged attacked the Romans at the same time under Vercingetorix’ command. The Roman legionaries had to defend themselves against an army that outnumbered them and was attacking from two sides. A nightmare!

This third attack was the decisive battle: for hours, the Romans fought on both fronts until the relief army had to retreat. Vercingetorix, too, ended the battle at this point. On the next day, he sent a messenger to Caesar to offer him the surrender of Alesia. The latter accepted – Vercingetorix was to become an impressive part of Caesar’s triumphal procession. In exchange, he was willing to spare the oppidum.

Remains of the Battle

At MuséoParc, events can be reconstructed in detail through archaeological finds. Even the introduction is just perfect: In a movie, several people that are completely unaware of history talk about what they think to know about Gaul and Alesia. Their statements are commented on in the background through images of popular culture in an incredibly humorous way. This causes the viewer to now laugh about the interviewees or their answers, but about their ideas. And while you are still laughing, you realise somewhat dismayed that you share some of these ideas, and probably would not have had better answers to many of the questions.

Then you set out to explore the exhibition, where real objects are combined with models, films, reconstructions and games in a truly commendable way. Therefore, you will not even notice how the time flies while you spend much more time than expected in the few rooms of the museum. If you think that your limited knowledge of French would hinder you from experiencing such a thing, you are wrong. At MuséoParc, all information is given in three languages: French, English and German. Every film has English and German subtitles, and you can choose one of the three languages at every audio station. And the translations are truly excellent!

Coin Finds

Of course, there are also numerous coins on display. They are included in the exhibition as one of many groups of found objects. I was especially moved by a small hoard of Celtic coins, which was probably buried by a soldier or a citizen of the oppidum. He was not able to recover them …

An Overview of the Battlefield

The way in which the place is incorporated into the exhibition is also ingenious! The rooftop of the museum offers a magnificent view of the surrounding area. And this view is explained in detail. Like an old-fashioned showcase, a wooden frame only reveals part of the landscape. These spots are then commented on in an idiot-proof manner, including pictures of what you see with a circle surrounding the area that is talked about. In this way, you can imagine bit by bit where every part of the battle took place.

The Myth of Alesia

MuséoParc does not stop at bringing the events of the battle back to life. They also give extensive information on the role of the myth of Alesia for the perception of history and identity in France. Did you know, for example, that Napoleon III worked on a biography of Caesar and wanted to identify the places of the battles in France? For this purpose, he commissioned and financed numerous exhibitions, including those in Alise-Sainte-Reine. His research drive had the side effect of promoting the field of archaeology, which developed at an impressive speed. In 1862, he decided to build France’s first archaeological national museum to exhibit his finds.

But let us get back to Alesia. A graduate of the military college called Eugène Stoffel identified Alise-Sainte-Reine as ancient Alesia, which resulted in him being appointed director of the excavations there. We owe many of the crucial finding about this place to him, and when the excavations ended in 1865, Napoleon III erected a huge monument to Vercingetorix there. By the way, he is depicted with open hair. The winged helmet, which we can see on many later depictions, had not been associated with him yet.

The Winged Helmet – a Truly German Invention for a French Hero

In case you ever wondered why Asterix and the like wore winged helmets, I have the answer for you.

Winged helmets are anything but historically correct. They were invented by a costume designer called Carl Emil Döppler, who was responsible for Wagner’s Ring der Nibelungen (Ring of the Nibelung). He created all the horned and winged helmets that adorn Viking and Celtic heads to this day; Wagner, however, was quite repelled by this headgear and only refrained from replacing the costumes due to a lack of time and money.

A lack of money was also the reason why the Wagner couple sold the original sceneries and costumes a few years later to Angelo Neumann, who organised a tour through Europe with a travelling ensemble performing the Ring des Nibelungen. Between September 1882 and June 1883, there were 135 performances – all of them with winged helmets. The performances established a trend. Even in my school days, Lohengrin always appeared on the stage of the Munich National Theatre with a winged helmet.

So, it is no surprise that every person with a bit of general education imagines the typical Celt or Germanic (the average citizen probably does not make a difference between the two) with a magnificent winged helmet.

The Gaul as a French Figure of Identification

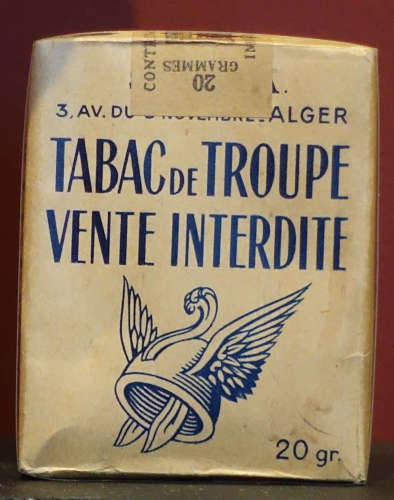

Ever since, the winged helmet has adorned cigarette packs, chocolate boxes, medals and statues. In the First World War, the Gallic warrior encouraged soldiers in the trenches to resist the enemy; in the Second World War, he encouraged the Vichy regime to cooperate with the conquerors, i.e., to fight for the merciless endurance of the Résistance. An entire hall filled with Gallic warriors wearing winged helmets on posters, medals, plates, comics and much more testifies to the vigour of this figure.

A Trip to the Oppidum of the Mandubii

If you are done with the tour through MuséoParc, there is more to discover. Only three kilometres from the park, there is the exhibition site of Alesia, where a flourishing Gallo-Roman settlement was established under Roman rule. A small theatre, a temple of Jupiter, a basilica – nothing that you would not have already seen in a better state in other places. Only the structures might be of interest as they indicate that there was a guild of blacksmiths, and indeed Alesia was known for its metal products in the Roman imperial period.

A Last Glance at Vercingetorix

And, of course, one must get a last glance at the great Vercingetorix. The site is quite relaxed for a national monument – no huge crowds, just a few hikers and school classes that enjoy a picknick on the lawn.

And this is truly impressive as well: Alesia is really relaxed about having the burden of being a national cultural heritage site. If you ever travel around the region, you should definitely go there!