Coins from the Era of Marius and Sulla Discovered in Tuscany

by Lisa Scheffert, translated by Maike Meßmann

When walking through a recently deforested area near Livorno, Italy, in November 2021, an archaeologist found silver coins on the ground. He quickly realised how important this find was and informed the relevant authorities. Excavations ensued and revealed that there was a total of 175 denarii, which had been hidden in a ceramic vessel.

The coins are from the time of the Roman Republic and, besides a few exceptions, all of them are of remarkable quality. The large number of coins from the time between 157 and 82 BC led experts to believe that we might be dealing with the savings of a soldier who fought in the Social War and probably also in the civil war between Sulla and Marius.

The silver treasure was found on the premises of a wine-growing estate in the region of Collesalvetti. The trees of the forested area had been cut shortly before, which is why the ancient coins were visible to the naked eye. Luckily, they were discovered by a trained expert: an archaeologist who examined the area. He immediately informed the relevant authorities and monitored the hoard until a small team came to carry out an excavation. All coins of the hoard were recovered and experts assume that the hoard still comprises all of the coins that had originally been buried.

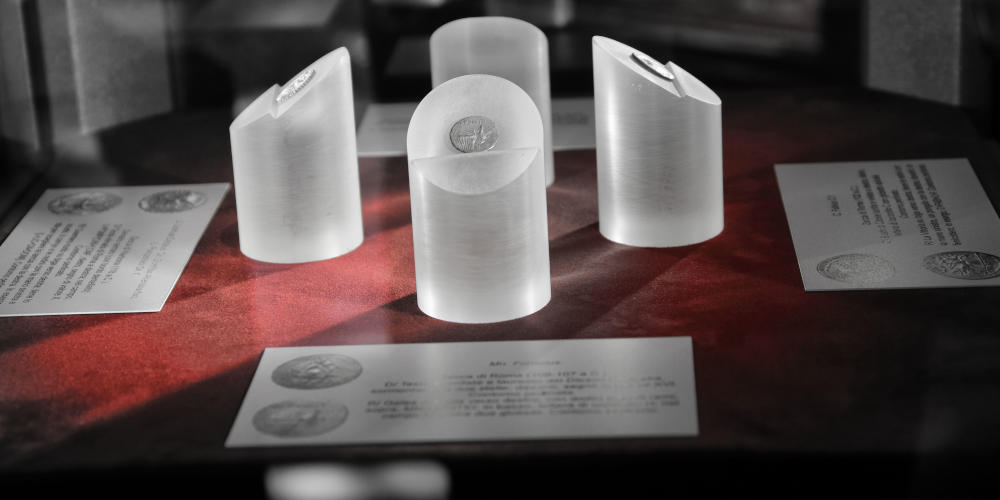

Once the hoard had been recovered, it could be examined thanks to a collaboration of the archaeologists and the Natural History Museum of the Mediterranean in Livorno. Recording, documenting and cataloguing all the coins took more than a year. In May 2023, the exhibition in the Natural History Museum of the Mediterranean in Livorno finally opened and the coins were first presented to the public. Visitors were able to examine the treasure until 2 July 2023. A catalogue was published to complement the exhibition, funded by the Province of Livorno and the Region of Tuscany.

Almost all of the coins hardly show any signs of wear and tear, which is why it can be assumed that they did not circulate for a long time. Only two coins broke, but it was possible to put them together again. Regarding one specimen, only a little more than half the coin remains. Experts date the coins to the time between 157 and 82 BC. The oldest coins of the hoard were minted between 157 and 110 BC. Only two or three specimens of this period are part of the hoard. Most of the pieces are from the years between 91 and 88 BC and thus from the time of the Social War. After that, the number of coins decreases until the year of 82 BC. Since the youngest specimen was minted in 82 BC, it is likely that the treasure was buried in that very year. Researchers also found that, except for one coin minted around 118 BC in Narbonne, all specimens had been produced in Rome.

In 82 BC, the Roman general and later dictator Sulla marched on Rome against Marius. Experts assume that the treasure was buried before Sulla’s victory, when central and northern Italy were controlled by Marius. Gaius Marius fundamentally reformed the Roman army in the years between 107 and 104 BC. In the context of the campaigns against the Cimbri and the Teutons, a citizen militia was turned into a professional army of volunteers – the Marian military reform. Since the hoard of 175 denarii corresponds to the pay of a soldier that served in the military for one and a half years, it is possible that its owner was a legionary. Maybe he buried his savings in this place once he came home and did not have the possibility to recover the money later.

This short YouTube video shows the structure of the exhibition and a few coins: