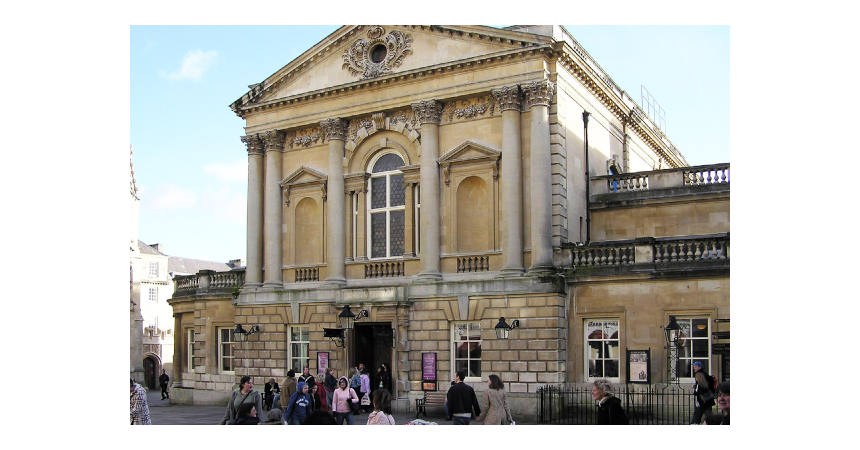

Roman Baths at Bath

Wenn es kein Logo gibt, wird diese Spalte einfach leer gelassen. Das Bild oben bitte löschen.

(Dieser Text wird nicht dargestellt.)

Abbey Church Yard

Bath, BA1 1LZ

Tel: ++44 (0)1225 477785

The once ancient Roman city of Bath, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, is situated on the Avon River in Wessex. Because of its natural hot springs, the city has been a popular resort for almost two millennia.

When Romans occupied Britain in the 1st century AD, they built their own bath complex along with an ingenious under-the-floor heating system, or hypocaust. Because they also recognized the medicinal properties of the natural spring, the Romans combined the name of their goddess of war and medicine, Minerva, with the local Celtic goddess of healing, Sulis, as Sulis Minerva, and renamed the city in 43 AD as Aquae Sulis in her honor.

The Great Bath

Although the Romans built their bath complex almost 2,000 years ago, it fell into ruin and the open-air Great Bath, the heart of the city’s spa complex, was not discovered until the 1870s. All of the surrounding building, terrace, and statues of Roman dignitaries are from the late 19th century. Once past the entrance hall, the Museum complex contains several baths which are below street level, a temple to Sulis Minerva, the Sacred Spring, and a museum exhibit.

The Great Bath is lined with 45 sheets of lead and is about five feet deep. It is supplied with water from the natural spring at a constant temperature of 46 degrees Celsius (115 degrees Fahrenheit).

Roman Coins Found

Near the end of the Museum complex, there is a small exhibit of some of the more than 12,000 coins recovered from the hot Sacred Spring, thrown by Romans wishing good luck from the gods. This is the largest votive collection in Britain. Although the quality of the 40 or so coins on display is nowhere near the level one would expect of those on display in say, the British Museum, these coins nonetheless do serve an educational purpose to those unfamiliar with ancient Roman coinage.

The exhibit explains that most Roman coins (gold, silver, and bronze) reached Britain via the army and civil service. Among those shown are: a silver antoninianus of Philip II (247–249 AD), a bronze centenionalis of Magnentius (350–353), and a gold solidus of Valens (364–378), with both obverse and reverse specimens.

Other coins in the exhibit help to explain that the obverse of Roman coins normally bore the image of the emperor with the legend giving his name and titles in abbreviated form, as illustrated by bronze coins of Tiberius, Claudius, Nero, Vespasian, Antonius Pius, Commodus, and Diocletian.

Coin Motives

Very often following the emperor’s death, coins were struck, giving his newly divine status, such as the bronze coin of the Emperor Augustus (27 BC–14 AD). One commemorative coin shown is that of Faustina, the wife of Antionius Pius (138–161 AD), who chose to honor a member of the Imperial household with his wife’s portrait rather than his own.

The exhibit also explains that the reverse designs of Roman coins were generally used as a means of conveying throughout the empire the military and political achievements of the emperor or events about his family. Popular gods, such as Neptune and Sol, and symbolic figures, like Liberty and Virtue, were portrayed, often standing with the emperor as head of the state religion. Animals, such as boars, elephants, and the she-wolf (with the mythical founders of Rome—Romulus and Remus), were also popular motifs. Coins found in the Sacred Spring also serve to pinpoint the dates during which the baths were in use.

This text was written by Howard M. Berlin and first published in his book Numismatourist in 2014.

You can order his numismatic guidebook at Amazon.

Howard M. Berlin has his own website.