Human faces, part 40: The pirate queen

courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “Menschengesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Elizabeth I, Queen of England (1558-1603). Shilling, 1591-1595. Crowned bust of Elizabeth I to the left. On the right, coat of arms on a long cross. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

Elizabeth I reigned at a time when England was considered rather backward by her continental contemporaries. Especially the country’s arms production could not hold up to the standards set by Flanders and Brabant, Augsburg and Nuremberg. The reason behind this was the low output of copper and zinc mining. Of iron, on the other hand, the English had more than enough. Still, iron casting was still in the early stages of development and the first canons, manufactured from cast iron in Sussex thanks to special funding from Henry VIII, did not inspire a lot of confidence. They did, however, become an export hit during Elizabeth’s reign. They would never entirely match the quality of their bronze counterparts, but their price and light weight made them unbeatable.

Coronation portrait of Elizabeth I. Source: Wikicommons.

The first to take advantage of this new achievement were tradesmen and explorers venturing into the Americas. Technically, the Spanish had prohibited access to “their” colonies. But then Spain was the enemy anyway, Catholic on top of that, and so the English captains did not consider it a crime to engage in some plundering and robbing as a side business of their actual trade. Of course, the queen had no notion of any such business – officially. Unofficially, she financially supported these enterprises.

Resistance to the pirates serving the queen was futile for two reasons: They possessed unusually large crews, against whom the Spanish merchant vessels, once boarded, were helpless. Secondly, the numerous iron canons on the English ships by far surpassed the firepower of the Spaniards’ arms.

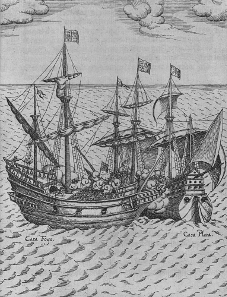

Levinus Hulsius, Capture of Cacafuego. Copperplate print , 1626. Source: Wikicommons.

The most famous privateer of his time was Sir Francis Drake. In 1580, he returned from his circumnavigation of the world with a fortune of 600,000 pounds on board. Without meeting with too much resistance, he had seized the “Cacafuego”, a Spanish treasure ship whose firepower was not as great as its name claimed. The loot from the Cacafuego consisted of 13 chests with silver coins, 26 tons of silver bullion bars, 72 pounds of gold as well as jewels and pearls.

Queen Elizabeth, constantly low on funds, was impressed by this treasure. She received half of the proceeds as her share of the profit, swore that she was innocent to the Spanish ambassador, and knighted Sir Francis Drake, who was later to win fame and go down in history for his defence of England against the Spanish Armada.

Our next episode takes us to Germany, where the city of Augsburg faces severe financial problems in the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “Menschengesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.